Osman v. United Kingdom - 23452/94 [1998] ECHR 101 (28 October 1998)

Citation: Osman v. United Kingdom - 23452/94 [1998] ECHR 101 (28 October 1998)

Rule of thumb 1: Can the state ever claim blanket immunity from liability for any circumstance where they cause a person injuries? No, there can never be blanket immunity. If the state is grossly negligent & causes a person damages then the state must pay damages for this – it is a violation of the right to a fair trial & the right to a remedy for this not to be allowed.

Rule of thumb 2: Can you ever claim damages from the Police? Yes, if their actions are particularly reckless.

Judgment:

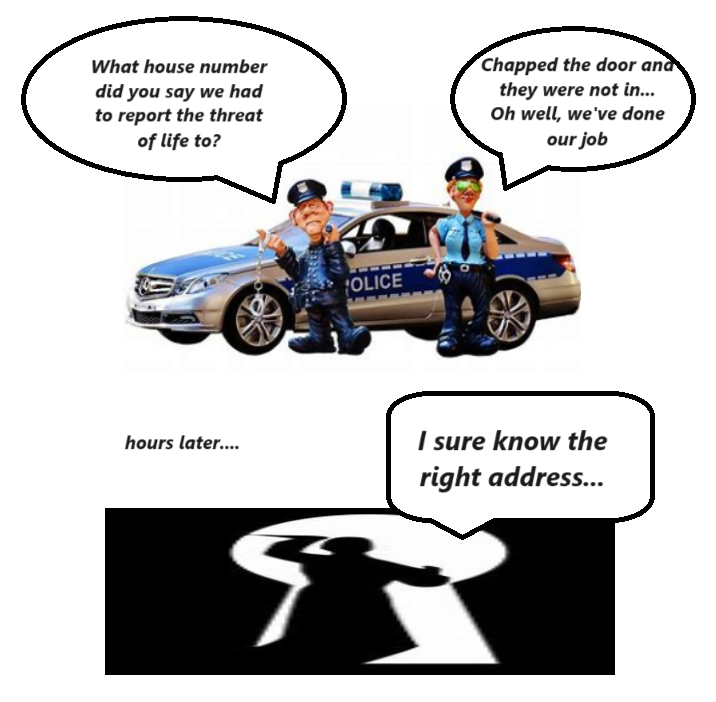

The Court in this case confirmed that the state’s institutions have a positive obligation to take steps to protect a person’s life, rather than just not be directly involved in the taking of someone’s life. The facts of this case were that the police had information that Osman might be in danger due to one of his school teachers, Paget-Lewis, taking an obsessed fascination with him and stalking him. Osman was not warned about this and Paget-Lewis killed him. Osman’s family argued that this violated their right to life, their right to a fair trial and their right to a remedy. The Court held that Osman’s article 2 right to life in this particular set of circumstances was not violated by the police failing to take measures to protect him, as it was noted that the teacher was not even suspended from duties due to the lack of a truly credible threat to life, indeed continuing to teach at the school, but they did hold that blanket immunity for the police in legal actions raised to consider whether the police should have done more to protect him or not did violate the right to a fair trial. The Court held that the right to a remedy was not violated as the family did gain access to a Court to make their case against the police – they were not completely shut out from this and could indeed appeal all the way to the ECHR where they eventually obtained damages in the end – rather it was just the verdict that the police had blanket immunity from any litigation questioning how they carried out their duties that was the problem. The Court therefore all in all confirmed that the Police and other state institutions have a positive duty to warn people whose lives may be in danger, and if they do not properly warn people in the future when the threat to the life of a person is more credible then it could constitute a breach of the right to life, ‘Against that background the Court notes that the applicants' claim never fully proceeded to trial in that there was never any determination on its merits or on the facts on which it was based. The decision of the Court of Appeal striking out their statement of claim was given in the context of interlocutory proceedings initiated by the Metropolitan Police Commissioner and that court assumed for the purposes of those proceedings that the facts as pleaded in the applicants' statement of claim were true. The applicants' claim was rejected since it was found to fall squarely within the scope of the exclusionary rule formulated by the House of Lords in the Hill case. The reasons which led the House of Lords in the Hill case to lay down an exclusionary rule to protect the police from negligence actions in the context at issue are based on the view that the interests of the community as a whole are best served by a police service whose efficiency and effectiveness in the battle against crime are not jeopardised by the constant risk of exposure to tortious liability for policy and operational decisions. Although the aim of such a rule may be accepted as legitimate in terms of the Convention, as being directed to the maintenance of the effectiveness of the police service and hence to the prevention of disorder or crime, the Court must nevertheless, in turning to the issue of proportionality, have particular regard to its scope and especially its application in the case at issue. While the Government have contended that the exclusionary rule of liability is not of an absolute nature (see paragraph 144 above) and that its application may yield to other public-policy considerations, it would appear to the Court that in the instant case the Court of Appeal proceeded on the basis that the rule provided a watertight defence to the police and that it was impossible to prise open an immunity which the police enjoy from civil suit in respect of their acts and omissions in the investigation and suppression of crime.The Court would observe that the application of the rule in this manner without further enquiry into the existence of competing public-interest considerations only serves to confer a blanket immunity on the police for their acts and omissions during the investigation and suppression of crime and amounts to an unjustifiable restriction on an applicant's right to have a determination on the merits of his or her claim against the police in deserving cases. In its view, it must be open to a domestic court to have regard to the presence of other public-interest considerations which pull in the opposite direction to the application of the rule. Failing this, there will be no distinction made between degrees of negligence or of harm suffered or any consideration of the justice of a particular case. It is to be noted that in the instant case Lord Justice McCowan (see paragraph 64 above) appeared to be satisfied that the applicants, unlike the plaintiff Hill, had complied with the proximity test, a threshold requirement which is in itself sufficiently rigid to narrow considerably the number of negligence cases against the police which can proceed to trial. Furthermore, the applicants' case involved the alleged failure to protect the life of a child and their view that that failure was the result of a catalogue of acts and omissions which amounted to grave negligence as opposed to minor acts of incompetence. The applicants also claimed that the police had assumed responsibility for their safety. Finally, the harm sustained was of the most serious nature. For the Court, these are considerations which must be examined on the merits and not automatically excluded by the application of a rule which amounts to the grant of an immunity to the police’, at 148-152 Judge President Herbert Petzold, ‘The weight thus attached to the exception in this case, together with its broad reach and the exclusive application given to it, combined in my view to produce a disproportionate limitation on the applicants' right of access to court. I therefore concurred in the conclusion stated in paragraph 154 of the judgment. For me the exception, operating in this way, is an inappropriately blunt instrument for the disposal of claims raising human rights issues such as those of the present case’, Judge Sir John Freeland concurred here at para 5 of his Opinion

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.