Adams v Cape Industries plc: CA 2 Jan 1990

Citation:Adams v Cape Industries plc: CA 2 Jan 1990

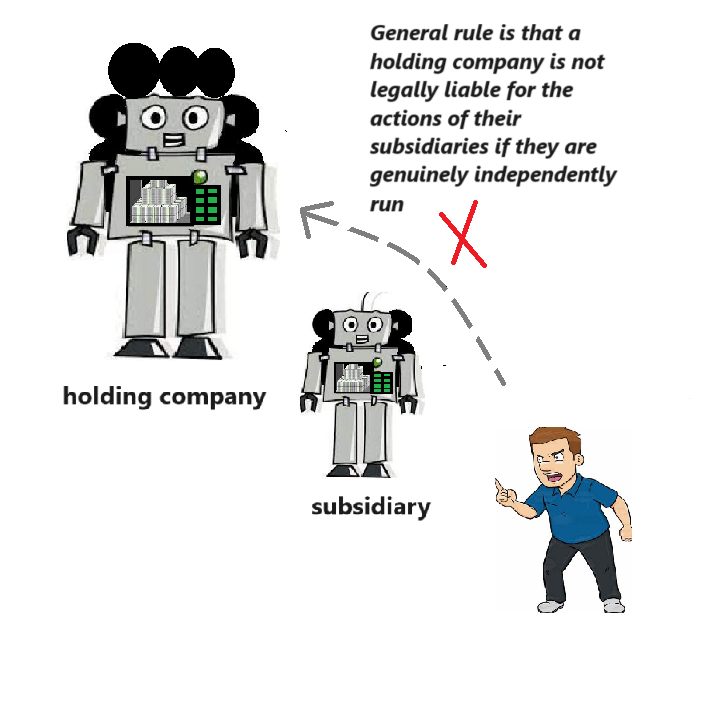

Rule of thumb 1: If a subsidiary company is not paying its debts, can the holding company be sued? As a general rule, no, separate personality applies. If special circumstances showing that the 2 companies were closely intertwined can be shown, this may not apply. This is an example of such a case where special circumstances were not shown.

Rule of thumb 2: If a subsidiary company causes industrial diseases to its workers, can the holding company be sued? As a general rule, no, not unless special circumstances can be shown.

Judgment:

The facts of this case were that Cape started out as a mining company in the late 1800’s and continued so throughout the 1900’s. As Cape grew in size they began to set up mines throughout the world, however, rather than actively continue mining, they set up as a holding company. They owned various companies across the world, and operated business support services – however, once they had appointed directors, they let the directors get on with the operations themselves and make all the day-to-day decisions. One of Cape’s subsidiaries, Capco in South Africa, mined asbestos, and they passed this on to another of Cape’s subsidiaries in Texas, an American company NCAA. However, the asbestos which Capco and NCAA had supplied to factors in Texas to be used as insulation was not properly packaged and manufactured – this meant that tiny asbestos dust particles broke off, went into the air, and then ended up in people’s lungs, causing severe lung dysfunction and eventually cancer. Almost 1000 people in Texas had problems with this. These people in Texas raised a class action and the American Court ruled that Cape Industries were liable to pay the money. Cape refused to pay the money and one of the injured parties sued Cape in the UK Courts. The UK Court ruled that Cape were not liable to pay the money because they were a ‘holding company’, and as a general rule, holding companies were not liable for the decisions of their subsidiaries who they provided business support services to, ‘Mr. Morison submitted that the court will lift the corporate veil where a defendant by the device of a corporate structure attempts to evade (i) limitations imposed on his conduct by law; (ii) such rights of relief against him as third parties already possess; and (iii) such rights of relief as third parties may in the future acquire. Assuming that the first and second of these three conditions will suffice in law to justify such a course, neither of them apply in the present case. It is not suggested that the arrangements involved any actual or potential illegality or were intended to deprive anyone of their existing rights. Whether or not such a course deserves moral approval, there was nothing illegal as such in Cape arranging its affairs (whether by the use of subsidiaries or otherwise) so as to attract the minimum publicity to its involvement in the sale of Cape asbestos in the United States of America. As to condition (iii), we do not accept as a matter of law that the court is entitled to lift the corporate veil as against a defendant company which is the member of a corporate group merely because the corporate structure has been used so as to ensure that the legal liability (if any) in respect of particular future activities of the group (and correspondingly the risk of enforcement of that liability) will fall on another member of the group rather than the defendant company. Whether or not this is desirable, the right to use a corporate structure in this manner is inherent in our corporate law. Mr. Morison urged on us that the purpose of the operation was in substance that Cape would have the practical benefit of the group's asbestos trade in the United States of America without the risks of tortious liability. This may be so. However, in our judgment, Cape was in law entitled to organise the group's affairs in that manner and (save in the case of A.M.C. to which special considerations apply) to expect that the court would apply the principle of Salomon in the ordinary way...’ turn on the wording of particular statutes or contracts, the court is not free to disregard the principle of Salomon… merely because it considers that justice so requires.’ ‘to the layman at least the distinction between the case where a company itself trades in a foreign country and the case where it trades in a foreign country through a subsidiary, whose activities it has full power to control, may seem a slender one….’ Slade LJ

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.