Assicurazioni Generali SpA v Arab Insurance Group (BSC) [2002] EWCA Civ 1642

Citation: Assicurazioni Generali SpA v Arab Insurance Group (BSC) [2002] EWCA Civ 1642

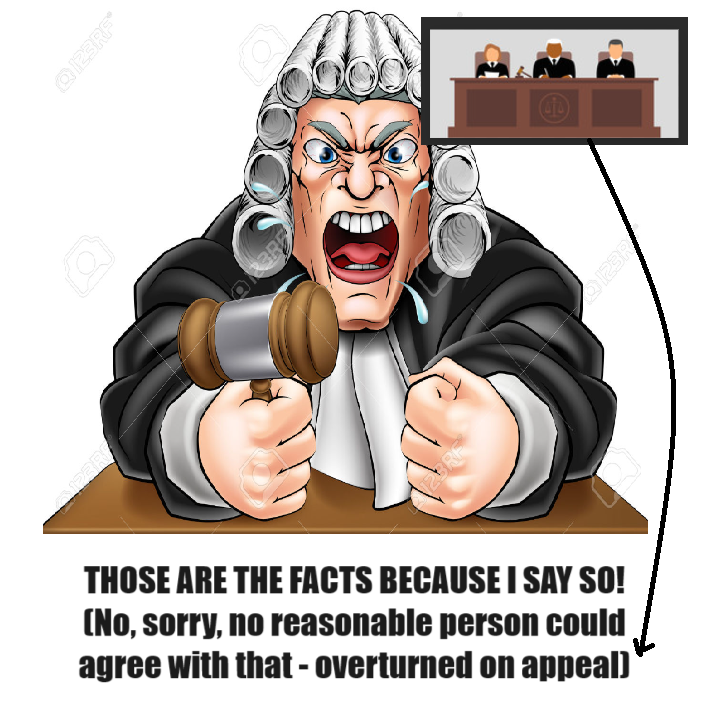

Rule of thumb: How do you get a fact held by a Lower Court Judge overturned? It is difficult - the test is that there has to be ‘no possibility for reasonable disagreements’.

Ratio-decidendi:

‘Bearing these matters in mind, the Appeal Court conducting a review of the trial judge’s decision will not conclude that the decision was wrong simply because it is not the decision the appeal judge would have made had he or she been called upon to make it in the court below. Something more is required than personal unease and something less than perversity has to be established. The best formulation for the ground in between where a range of adverbs may be used – "clearly", "plainly", "blatantly", "palpably" wrong, is an adaptation of what Lord Fraser of Tullybelton said in G v G (Minors: Custody Appeal) [1985] 1 W.L.R. 642, 652, admittedly dealing with the different task of exercising a discretion. Adopting his approach, I would pose the test for deciding whether a finding of fact was against the evidence to be whether that finding by the trial judge exceeded the generous ambit within which reasonable disagreement about the conclusion to be drawn from the evidence is possible. The difficulty or ease with which that test can be satisfied will depend on the nature of the finding under attack. If the challenge is to the finding of a primary fact, particularly if founded upon an assessment of the credibility of witnesses, then it will be a hard task to overthrow. Where the primary facts are not challenged and the judgment is made from the inferences drawn by the judge from the evidence before him, then the Court of Appeal, which has the power to draw any inference of fact it considers to be justified, may more readily interfere with an evaluation of those facts. The judgment of the Court of Appeal in The Glannibanta (1876) 1 PD 283, 287, seems as apposite now as it did then:-

"Now we feel, as strongly as did the Lords of the Privy Council in the cases just referred to [The Julia 14 Moo P.C. 210 and The Alice L.R. 2 P.C. 245], the great weight that is due to the decision of a judge of first instance whenever, in a conflict of testimony, the demeanour and manner of the witnesses who have been seen and heard by him are, as they were in the cases referred to, material elements in the consideration of the truthfulness of their statements. But the parties to a cause are nevertheless entitled, as well on question of fact as on questions of law, to demand the decision of the Court of Appeal, and that court cannot excuse itself from the task of weighing conflicting evidence and drawing its own inferences and conclusions, even though it should always bear in mind that it has neither seen nor heard the witnesses, and should make due allowance in this respect." Ward LJ at 197

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.