Nisbet v John Orr, Chief Constable of the Strathclyde Police and North Lanarkshire Council, OHCS, [2002] ScotCS 101

Citation: Nisbet v John Orr, Chief Constable of the Strathclyde Police and North Lanarkshire Council, OHCS, [2002] ScotCS 101

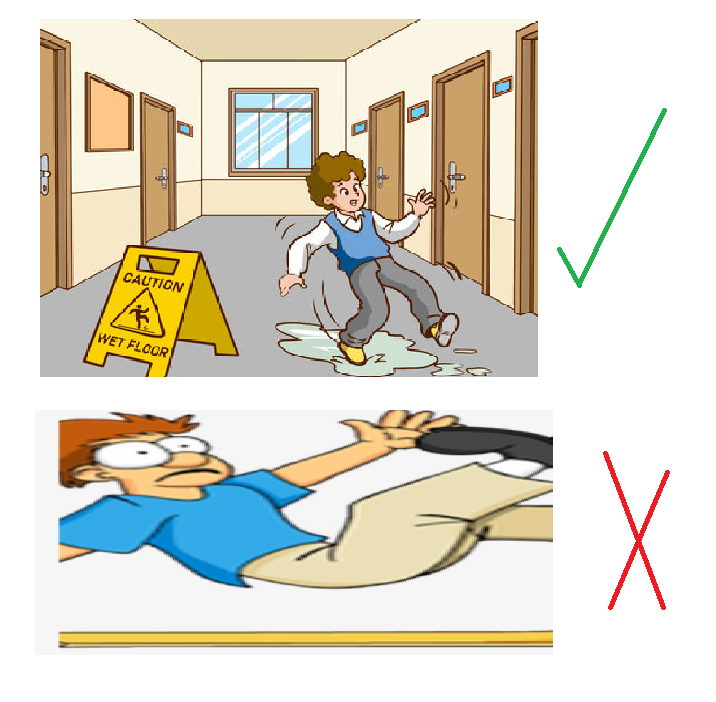

Rule of thumb: If you slip on a wet floor at work & injure yourself can you sue your employer? If the employer sub-contracts to a cleaner, and they did this, then the cleaner is responsible & not the employer. If the person slips on a carpet which was wet this is not a claim, as there is no foreseeability of wet carpets being slippery, however, if it is another floor surface that is mopped, then warning signs should automatically be put up or else this is a valid claim.

Judgment:

The basic facts were a police officer in the Police Station slipped on a carpet which was wet from a leak and cleaned by a janitor & injured his back. The Court held that the employer was not responsible as they contracted out cleaning work. The Court further held that the cleaner was not responsible as there was no foreseeability that a wet carpet would be slipper & this was a freak, fluke, & one-off accident which the finger of blame could not be pointed at anyone for.

Ratio-decidendi:

‘It is not said that the first defender was in control of the pursuer’s workplace at the time of the accident, and more importantly in terms of regulation 4(2)(c) it is not said that he was in control of the matter which was the cause of the accident at the material time. The only averments made by the pursuer suggest that control over the relevant matter which caused the accident lay elsewhere. If there are no averments that the first defender was in some way in control of what happened, then the first defender cannot be held responsible for what happened’, Lord Wheatley

‘[14]I have however more difficulty with the second defenders' principal and more fundamental submissions, which refer to all of the duties of care averred against them by the pursuer. The essence of this argument was that there was simply no averments that would yield an inference that the janitor should have foreseen that the surface of the floor was slippery, either through the presence of water, or the presence of the deodorising agent, or both. There is nothing to suggest that he knew or ought to have known that someone walking on the floor would have been liable to slip or fall, because of its condition. There is therefore a complete absence of averments which sufficiently describe the necessary ingredient of foreseeability in the pursuer's case. Accordingly the pursuer's case has to be considered to be irrelevant. It might have been enough to suggest that the second defenders or their employee knew or ought to have known that the floor was in a slippery condition for whatever reason. But the pursuer does not even go as far as that in the present case. All that is said is that the janitor knew or ought to have known that if he failed to fulfil the duties of care incumbent upon him, then the accident would not have occurred. That, as a statement, is self-evidently correct so far as it goes. However what this averment does not indicate is the basis for suggesting that the janitor should have known that, for whatever reason, the floor would be slippery and that persons walking on such a floor would be liable to fall. Nor is it sufficient for the pursuer's to suggest in Condescendence (4) that the janitor should have touched the carpet after he had applied the deodorising agent in order to see if it was slippery. It is entirely unclear what the basis of this averment might be. It seems to suggest in the circumstances that a janitor must always test wet carpets which have been treated by a deodourising agent, by touching them in order to see whether they are slippery or not. This appears to me to be in effect an allegation of a further duty of care rather than an averment from which the question of foreseeability can be inferred. Accordingly I have come to the conclusion that the pursuer's averments against the second defenders essentially lack any specification of foreseeability on the part of the janitor vicariously held responsible for the pursuer's accident, and that this case too is irrelevant’, Lord Wheatley.

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.