Fairchild v Glenhaven Funeral Services Ltd & Ors [2002] UKHL 22 (20 June 2002)

Citation:Fairchild v Glenhaven Funeral Services Ltd & Ors [2002] UKHL 22 (20 June 2002)

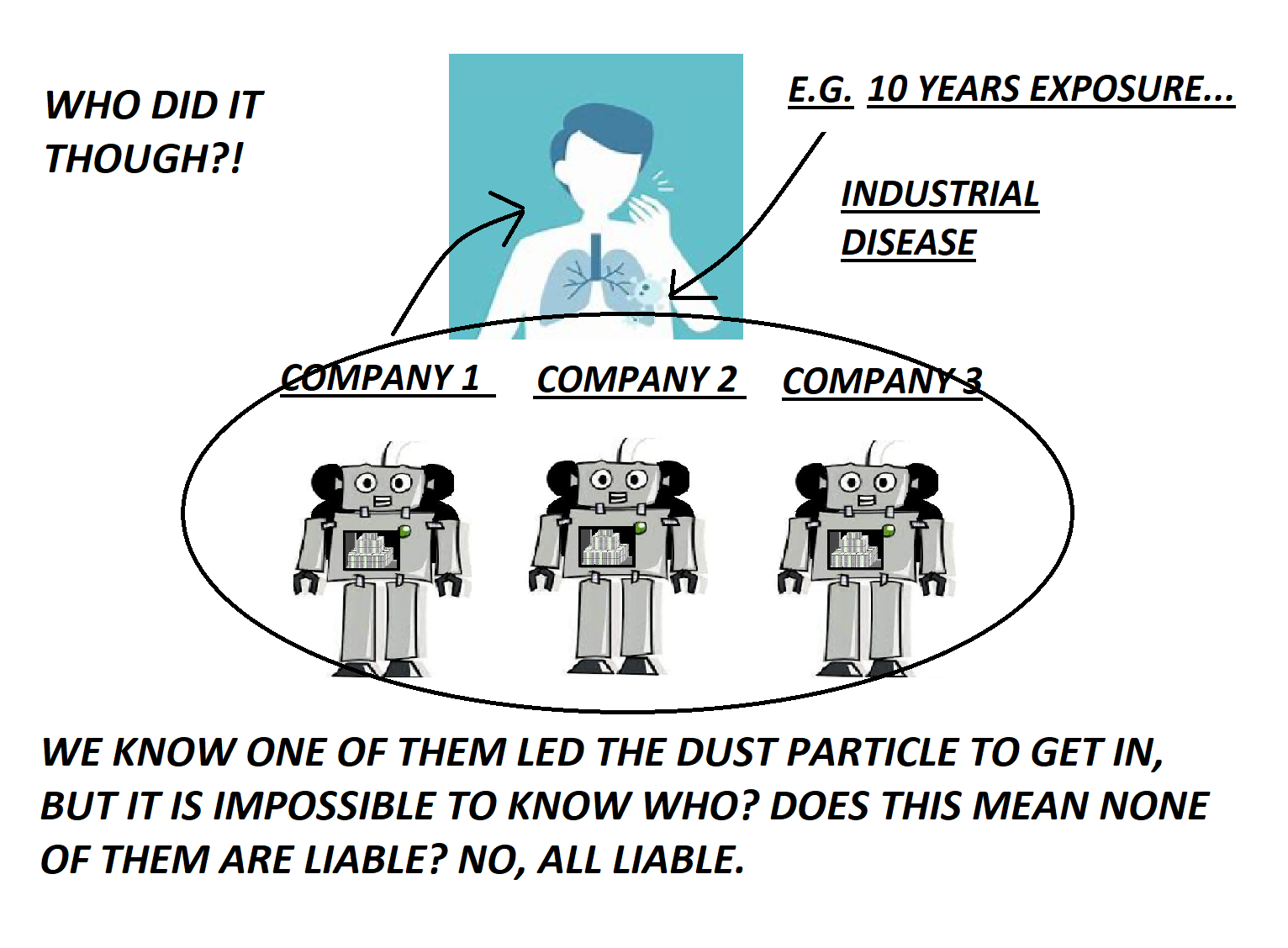

Rule of thumb:If you have an industrial disease, and could have picked it up in many places worked, who do you sue? You sue everyone who materially increase the risk of getting and they are all liable for the % to the risk they contributed.

Background facts:

The facts of this case were that people who worked in a funeral parlour preparing the bodies for the funeral service were exposed to dead bodies who had asbestos in their lungs, and these dead bodies passed it onto the funeral parlour workers. Many of these workers had worked in many places so they really had no idea where the asbestos would have got into their lungs.

Judgment:

The Court reaffirmed that as the funeral parlours had materially increased the risk of this, they were liable for the damages.

Ratio-decidendi:

‘2. The essential question underlying the appeals may be accurately expressed in this way. If (1) C was employed at different times and for differing periods by both A and B, and (2) A and B were both subject to a duty to take reasonable care or to take all practicable measures to prevent C inhaling asbestos dust because of the known risk that asbestos dust (if inhaled) might cause a mesothelioma, and (3) both A and B were in breach of that duty in relation to C during the periods of C's employment by each of them with the result that during both periods C inhaled excessive quantities of asbestos dust, and (4) C is found to be suffering from a mesothelioma, and (5) any cause of C's mesothelioma other than the inhalation of asbestos dust at work can be effectively discounted, but (6) C cannot (because of the current limits of human science) prove, on the balance of probabilities, that his mesothelioma was the result of his inhaling asbestos dust during his employment by A or during his employment by B or during his employment by A and B taken together,is C entitled to recover damages against either A or B or against both A and B?’, Lord Bingham, ‘60. The problem in this appeal is to formulate a just and fair rule. Clearly the rule must be based upon principle. However deserving the claimants may be, your Lordships are not exercising a discretion to adapt causal requirements to the individual case. That does not mean, however, that it must be a principle so broad that it takes no account of significant differences which affect whether it is fair and just to impose liability. 61. What are the significant features of the present case? First, we are dealing with a duty specifically intended to protect employees against being unnecessarily exposed to the risk of (among other things) a particular disease. Secondly, the duty is one intended to create a civil right to compensation for injury relevantly connected with its breach. Thirdly, it is established that the greater the exposure to asbestos, the greater the risk of contracting that disease. Fourthly, except in the case in which there has been only one significant exposure to asbestos, medical science cannot prove whose asbestos is more likely than not to have produced the cell mutation which caused the disease. Fifthly, the employee has contracted the disease against which he should have been protected. 62. In these circumstances, a rule requiring proof of a link between the defendant's asbestos and the claimant's disease would, with the arbitrary exception of single-employer cases, empty the duty of content. If liability depends upon proof that the conduct of the defendant was a necessary condition of the injury, it cannot effectively exist. It is however open to your Lordships to formulate a different causal requirement in this class of case. The Court of Appeal was in my opinion wrong to say that in the absence of a proven link between the defendant's asbestos and the disease, there was no "causative relationship" whatever between the defendant's conduct and the disease. It depends entirely upon the level at which the causal relationship is described. To say, for example, that the cause of Mr Matthews' cancer was his significant exposure to asbestos during two employments over a period of eight years, without being able to identify the day upon which he inhaled the fatal fibre, is a meaningful causal statement. The medical evidence shows that it is the only kind of causal statement about the disease which, in the present state of knowledge, a scientist would regard as possible. There is no a priori reason, no rule of logic, which prevents the law from treating it as sufficient to satisfy the causal requirements of the law of negligence. The question is whether your Lordships think such a rule would be just and reasonable and whether the class of cases to which it applies can be sufficiently clearly defined. 63. So the question of principle is this: in cases which exhibit the five features I have mentioned, which rule would be more in accordance with justice and the policy of common law and statute to protect employees against the risk of contracting asbestos-related diseases? One which makes an employer in breach of his duty liable for the claimant's injury because he created a significant risk to his health, despite the fact that the physical cause of the injury may have been created by someone else? Or a rule which means that unless he was subjected to risk by the breach of duty of a single employer, the employee can never have a remedy? My Lords, as between the employer in breach of duty and the employee who has lost his life in consequence of a period of exposure to risk to which that employer has contributed, I think it would be both inconsistent with the policy of the law imposing the duty and morally wrong for your Lordships to impose causal requirements which exclude liability... 67. I therefore regard McGhee as a powerful support for saying that when the five factors I have mentioned are present, the law should treat a material increase in risk as sufficient to satisfy the causal requirements for liability. The only difficulty lies in the way McGhee was explained in Wilsher v Essex Area Health Authority [1988] AC 1074. The latter was not a case in which the five factors were present. It was an action for clinical negligence in which it was alleged that giving a premature baby excessive oxygen had caused retrolental fibroplasia, resulting in blindness. The evidence was that the fibroplasia could have been caused in a number of different ways including excessive oxygen but the judge had made no finding that the oxygen was more likely than not to have been the cause. The Court of Appeal [1987] QB 730 held that the health authority was nevertheless liable because even if the excessive oxygen could not be shown to have caused the injury, it materially increased the risk of the injury happening’, Lord Hoffman

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.