Director General of Fair Trading v First National Bank [2001] UKHL 52

Citation:Director General of Fair Trading v First National Bank [2001] UKHL 52

Rule of thumb 1:Can penalty clauses ever be justified by an organisation? Yes, they can, if they actually reflect the cost incurred by the organisation and are not grossly exaggerative.

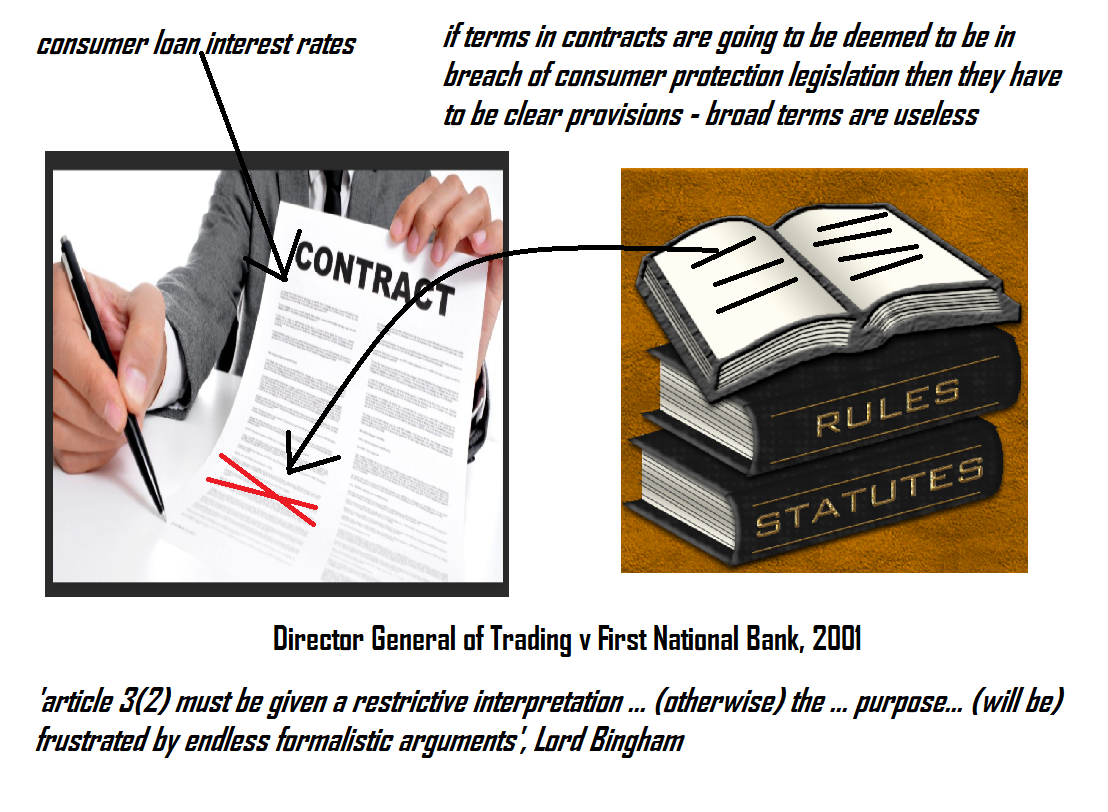

Rule of thumb 2:Do broad statutory provisions give Courts a lot of discretion? No, these are misnomers which give Courts no power or rights they can apply. In order to disapply a term in a consumer contract, the consumer protection statutes or regulations must be in point – broad statutory provisions or regulations are worthless.

Background facts:

The basic facts of this case were that the size of interest to be paid on consumer bank loans, such as overdrafts and short term loans, was questioned under section 3 and section 5 of the 1995 Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Regulations.

Parties argued:

It was argued by the Director General that based on the unfair contract terms that the rate was unreasonable in terms of section 3 and that the term breached good faith in terms of section 5. The bank argued in response that the cost of the banking system as a whole had to be taken into consideration, not just one aspect, and that when all of the costs of all the different parts of the business were taken into account the overall rates being charged for customer banking were at a reasonable rate meaning that the price was not a breach of section 3.

Judgment:

Banks are legally required to loan out money to consumers at a rate that is reasonable. The facts of this case were that the size of interest to be paid on commercial loans – such as overdrafts and short term loans – was questioned. It was argued based on the unfair contract terms that the rate was extortionate and not enforceable. The bank was able to show how they were calculating this rate at a reasonable price – they showed their rate alongside market rates and explained the volume work that had to be done to organise the moving of funds. The Courts held that whilst the rate was very high it was not sufficiently unreasonable to constitute a wholly unreasonable contract term in this instance.

The Court upheld the arguments of the bank and stated that the terms in these contracts did not breach the consumer protection laws. The Court affirmed that the sections being relied on were too general, meaning that these terms were basically 'paper tigers' which looked good on paper but had no practical effect in real life. The Court held that a restrictive interpretation of consumer protection statutes had to be taken to avoid endless arguments being made that terms of contracts breached them. This is a key case for defending consumer protection breaches.

Ratio-decidendi:

‘There is nothing unbalanced or detrimental to the consumer in that obligation [to repay with interest]; the absence of such a term would unbalance the contract to the detriment of the lender’, Lord Bingham.

‘The purpose of the Directive is twofold, viz the promotion of fair standard contract forms to improve the functioning of the European market place and protection of consumers throughout the European Community. The Directive is aimed at contracts of adhesion, viz "take it or leave it" contracts. It treats consumers as presumptively weaker parties and therefore fit for protection from abuses by the stronger contracting parties. This is an objective which must throughout guide the interpretation of the Directive as well as the implementing Regulations ... In any event, article 3(2) must be given a restrictive interpretation. Unless that is done article 3(2)(a) will enable the main purpose of the scheme to be frustrated by endless formalistic arguments as to whether a provision is a definitional or an exclusionary provision. Similarly, article 3(2)(b) dealing with "the adequacy of the price of remuneration" must be given a restrictive interpretation. After all, in a broad sense all terms of the contract are in some way related to the price or remuneration. That is not what is intended... It would be a gaping hole in the system if such clauses were not subject to the fairness requirement... to make regulations work’, Lord Steyn, ‘Good faith in this context is not an artificial or technical concept... It looks to good standards of commercial morality and practice. It lays down a composite test, covering both the making and the substance of the contract, and must be applied bearing clearly in mind the objective which the regulations are designed to promote. Fair dealing requires that a supplier should not, whether deliberately or unconsciously, take advantage of the consumer's necessity, indigence, lack of experience, unfamiliarity with the subject matter of the contract, weak bargaining position’, Lord Bingham

'article 3(2) must be given a restrictive interpretation ... (otherwise) the ... purpose... (will be) frustrated by endless formalistic arguments', Lord Bingham

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.