O'Neill v Phillips [1999] UKHL 24

Citation:O'Neill v Phillips [1999] UKHL 24

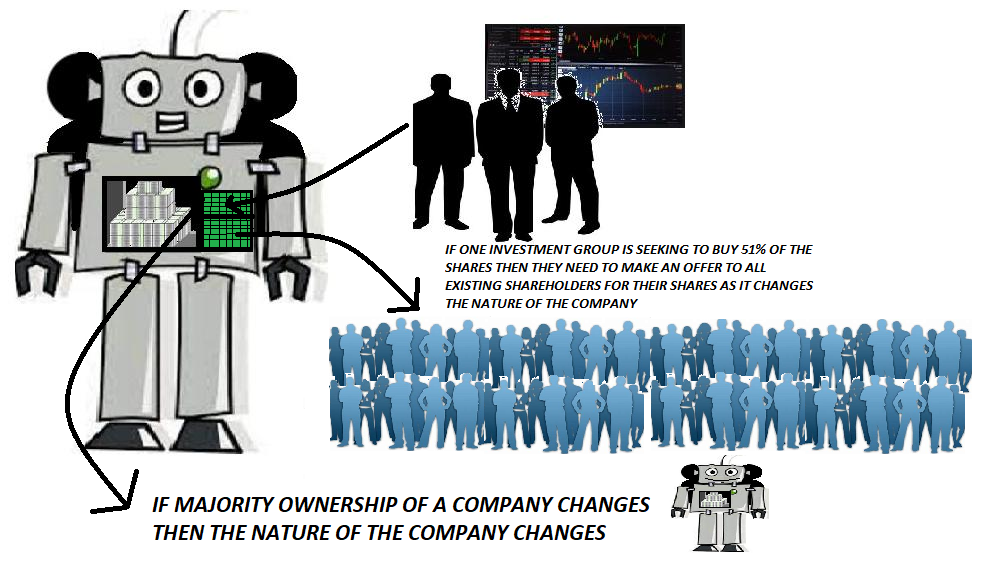

Rule of thumb:If a new investor is seeking to buy a controlling stake of shares in a company, do all shareholders have to be made an offer? Yes, if it is the shares needed to purchase a controlling stake all shareholders must be made an offer to sell.

Background facts:

The basic facts were that one shareholder was seeking to obtain a controlling interest in a company through buying shares from other shareholders, and the process by which this was done was challenged by 2 shareholders in this case.

Judgment:

The Court affirmed that where a majority shareholder is seeking to obtain an absolute majority over 75% to effectively bring an end to the company as it stands, then they have to make a fair offer to the other shareholders for the value of their shares based upon a fair sharing of all knowledge and independent valuations, and it is the duty of the shareholder purchasing the other shares to do this properly and get the valuations done.

This case further affirmed various points about the nature of partnerships, companies and association. It affirmed that the broad principle of good faith underpins partnership law. This carries to some degree as the underpinning of companies, although strict interpretation of the rules is important. This again carries on into the running of associations, although even less so than with companies where a strict interpretation of the rules and agreement is even more important.

Ratio-decidendi:

‘First, a company is an association of persons for an economic purpose, usually entered into with legal advice and some degree of formality. The terms of the association are contained in the articles of association and sometimes in collateral agreements between the shareholders. Thus the manner in which the affairs of the company may be conducted is closely regulated by rules to which the shareholders have agreed. Secondly, company law has developed seamlessly from the law of partnership, which was treated by equity, like the Roman societas, as a contract of good faith. One of the traditional roles of equity, as a separate jurisdiction, was to restrain the exercise of strict legal rights in certain relationships in which it considered that this would be contrary to good faith. These principles have, with appropriate modification, been carried over into company law. The first of these two features leads to the conclusion that a member of a company will not ordinarily be entitled to complain of unfairness unless there has been some breach of the terms on which he agreed that the affairs of the company should be conducted. But the second leads to the conclusion that there will be cases in which equitable considerations make it unfair for those conducting the affairs of the company to rely on their strict legal powers. Thus unfairness may consist in a breach of the rules or in using the rules in a manner which equity would regard as contrary to good faith’, Lord Hoffman The Court in this case affirmed the principle of ‘compulsory share transfer offer to minority shareholders in the event of a takeover (ending the association of shareholders in its current form)’ – it affirmed that where a majority shareholder is selling their majority stake a reasonable share transfer offer to purchase minority shareholders’ shares has to be made as well, and the valuation the minority shareholders are offered there has to be independently verified by an expert, ‘...Usually, however, the majority shareholder will want to put an end to the association. In such a case, it will almost always be unfair for the minority shareholder to be excluded without an offer to buy his shares... I think that parties ought to be encouraged, where at all possible, to avoid the expense of money and spirit inevitably involved in such litigation by making an offer to purchase at an early stage.... In the first place, the offer must be to purchase the shares at a fair value. This will ordinarily be a value representing an equivalent proportion of the total issued share capital. Secondly, the value, if not agreed, should be determined by a competent expert. The offer in this case to appoint an accountant agreed by the parties or in default nominated by the President of the Institute of Chartered Accountants satisfied this requirement... Thirdly, the offer should be to have the value determined by the expert as an expert. I do not think that the offer should provide for the full machinery of arbitration or the half-way house of an expert who gives reasons... Fourthly, the offer should, as in this case, provide for equality of arms between the parties. Both should have the same right of access to information about the company which bears upon the value of the shares and both should have the right to make submissions to the expert... Fifthly, there is the question of costs. In the present case, when the offer was made after nearly three years of litigation, it could not serve as an independent ground for dismissing the petition, on the assumption that it was otherwise well founded, without an offer of costs. But this does not mean that payment of costs need always be offered. If there is a breakdown in relations between the parties, the majority shareholder should be given a reasonable opportunity to make an offer (which may include time to explore the question of how to raise finance) before he becomes obliged to pay costs...’, Lord Hoffman

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.