Hunter v Canary Wharf Ltd [1997] A.C.655

Citation:Hunter v Canary Wharf Ltd [1997] A.C.655

Rule of thumb:This is a seminal case on nuisance where the Court affirmed 4 key fundamental principles in relation to the law of nuisance.

Rule of thumb 1:Can you get damages for nuisance by a neighbour? The first is that ordinary nuisance generally cannot lead to damages for stress and inconvenience as a remedy. There actually has to be psychiatric injury in order for there potentially to be personal injury damages. Damages can only be obtained for actual physical damage caused to the land.

Rule of thumb 2:Is there a link between nuisance and harassment? Yes. The Court in this case affirmed that there is an interface between nuisance and harassment cases, as where a legitimate actionable nuisance which is a breach of the law is brought to the attention of the other party and they continue to do it deliberately, then it becomes harassment at that stage for which damages for stress can be claimed.

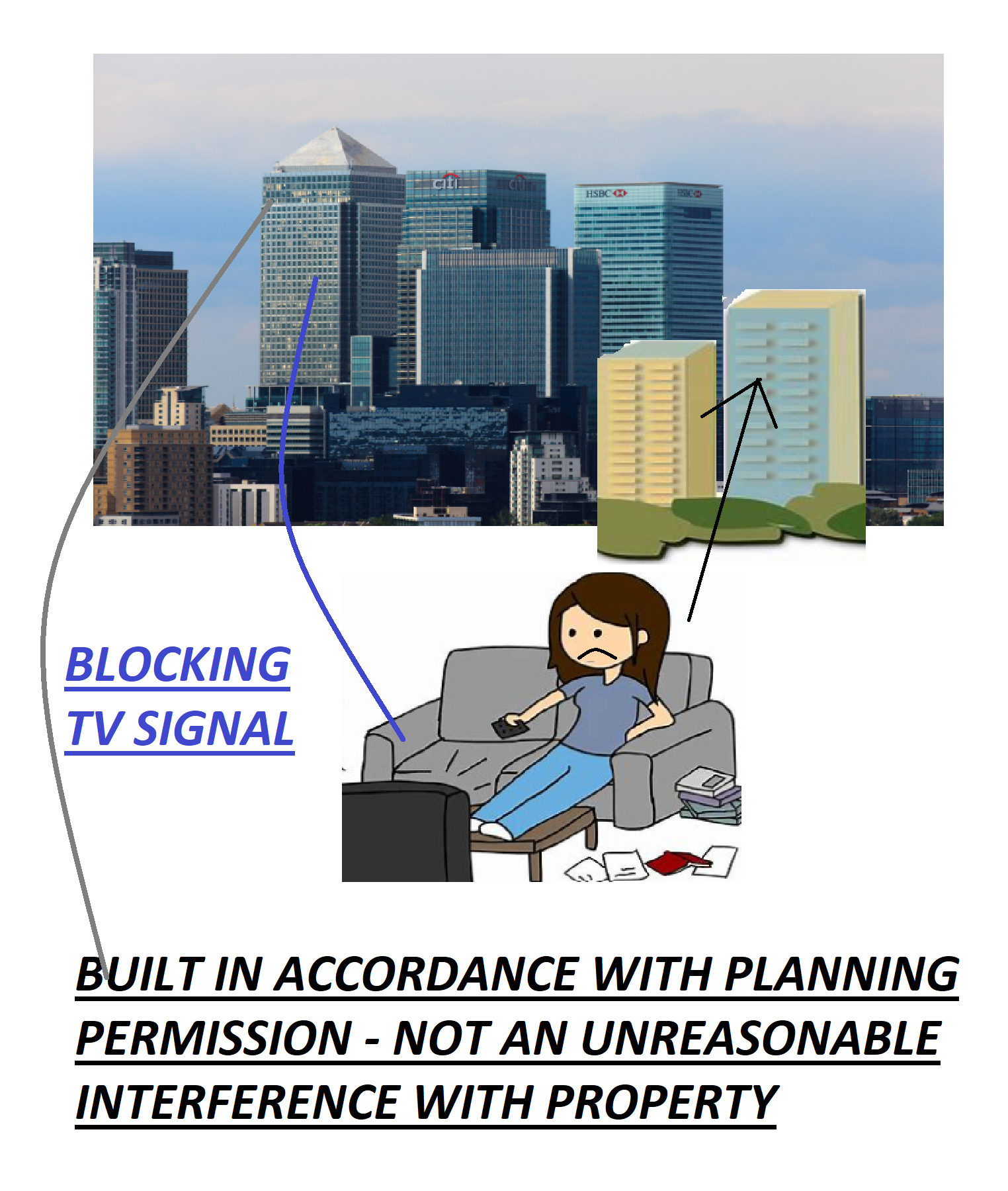

Rule of thumb 3:If land is being used in a way which is in accordance with planning permission, is this a valid defence? Yes, this is the typical defence to a nuisance action, or also to state that there is no law saying that this cannot be done. The Court also held that where a structure built in accordance with planning permission interferes with the noise, light or TV reception of a property, then this is deemed to be loss of view which is not actionable, and complaints in relation to this have to be made at the planning stage rather than once the structure is built.

Rule of thumb 4:Who can raise a nuisance case? A lodger cannot. It is only a tenant or owner who can. The Court also affirmed that it has to be a tenant or owner to bring the case to show sufficient title & interest, and that a lodger or licensee did not have grounds to get the case into Court.

Background facts:

The facts of this case were that a new tower was built which was so high it interfered with many residents’ TV signals.

Judgment:

The Court affirmed that damages for stress and inconvenience, as well as loss of money on their TV license, did not have to be paid by the owner of the building, as this was just deemed to be loss of view in accordance with planning permission which is not an actionable nuisance. As it happened a solution was found to improve the TV signal also.

Ratio-decidendi:

‘Private nuisances are of three kinds. They are (1) nuisance by encroachment on a neighbour's land; (2) nuisance by direct physical injury to a neighbour's land; and (3) nuisance by interference with a neighbour's quiet enjoyment of his land’, Lord Lloyd

‘[T]he case was concerned with the invasion of the privacy of the plaintiff's person, not the invasion of any interest which she might have had in any land. I would be uneasy if it were not possible by some other means to provide such a plaintiff with a remedy. But the solution to her case ought not to have been found in the tort of nuisance, as her complaint of the effects on her privacy of the defendant's conduct was of a kind which fell outside the scope of the tort’, Lord Hope of Craighead at 725...

"The perceived gap in Khorasandjian v Bush was the absence of a tort of intentional harassment causing distress without actual bodily or psychiatric illness. This limitation is thought to arise out of cases like Wilkinson v Downton [1897] 2 Q.B.57 and Janvier v Sweeney [1919] 2 K.B.316. The law of harassment has now been put on a statutory basis (see the Protection from Harassment Act 1997) and it is unnecessary to consider how the common law might have developed. But as at present advised, I see no reason why a tort of intention should be subject to the rule which excludes compensation for mere distress, inconvenience or discomfort in actions based on negligence: see Hicks v Chief Constable of the South Yorkshire Police [1992] 2 All.E.R.65. The policy considerations are quite different. I do not therefore say that Khorasandjian v Bush was wrongly decided. But it must be seen as a case on intentional harassment, not nuisance’, Lord Hope at 740.

‘In this case, however, the defendants say that the type of interference alleged, namely by the erection of a building between the plaintiffs’ homes and the Crystal Palace transmitter, cannot as a matter of law constitute an actionable nuisance. This is not by virtue of anything peculiar to television. It applies equally to interference with the passage of light or air or radio signals or to the obstruction of a view. The general principle is that at common law anyone may build whatever he likes upon his land. If the effect is to interfere with the light, air or view of his neighbour, that is his misfortune. The owner’s right to build can be restrained only by covenant or the acquisition (by grant or prescription) of an easement of light or air for the benefit of windows or apertures on adjoining land’, Lord Hoffman, ‘Private nuisances are of three kinds. They are (1) nuisance by encroachment on a neighbour's land; (2) nuisance by direct physical injury to a neighbour's land; and (3) nuisance by interference with a neighbour's quiet enjoyment of his land’, Lord Lloyd

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.