Investors Compensation Scheme Ltd. v West Bromwich Building Society [1997] UKHL 28

Citation:Investors Compensation Scheme Ltd. v West Bromwich Building Society [1997] UKHL 28

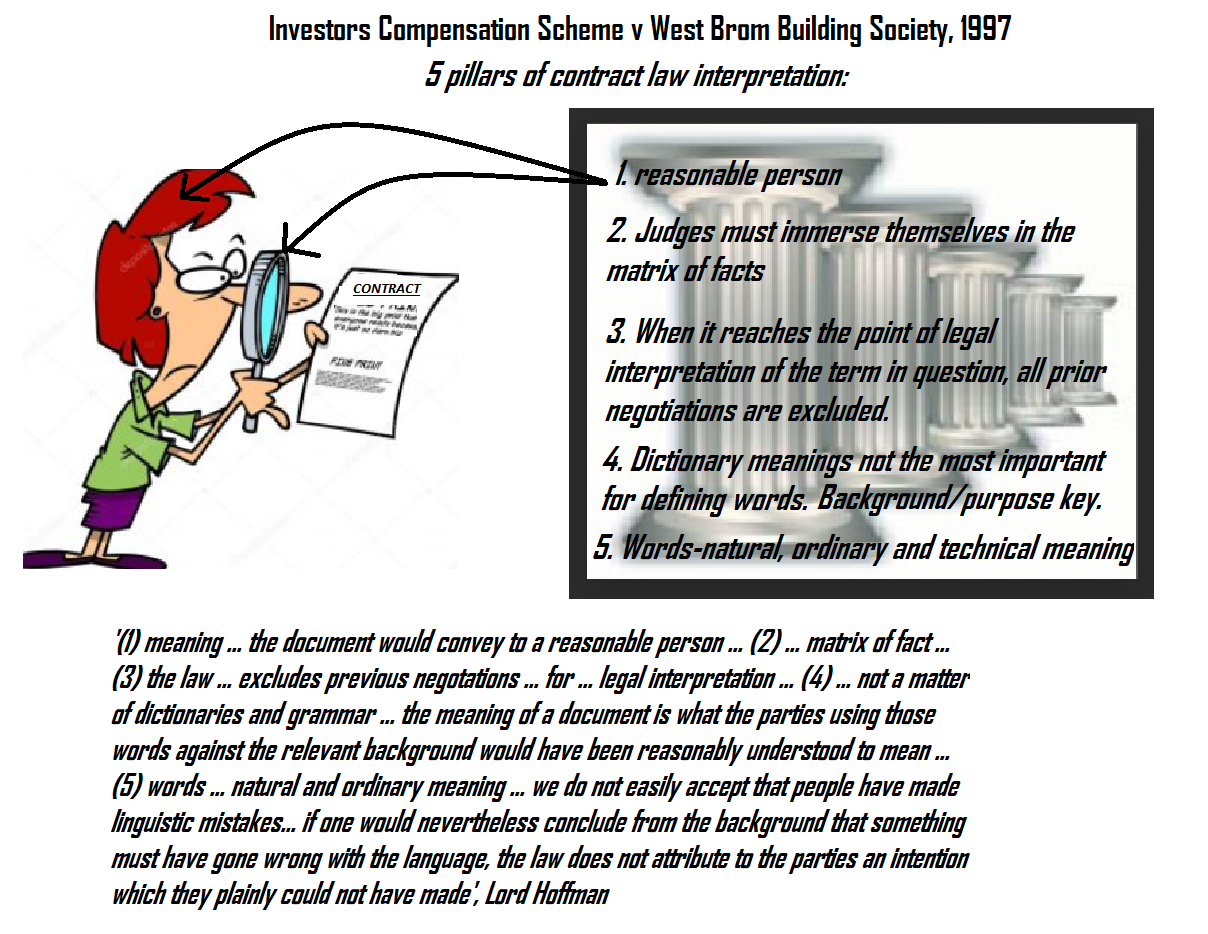

Rule of thumb 1:What is the key method for interpreting a contract? There are 5 seminal rules of contract terms interpretation: (1) Words given dictionary meaning; (2) a Judge can only interpret the meaning after they have immersed themselves in the matrix of facts; (3) previous negotiations are background facts and not aids to interpretation; (4) where it can be shown that technical non-dictionary definitions of words would have been used, these definitions can replace the dictionary definitions; and (5) it is presumed that there are not mistakes in the words and mistakes have to be obvious to be retrospectively amended.

Rule of thumb 2:Can a person’s legal claim be bought off them by another party? No, the original person with the claim must be the person who pursues or defends it and they cannot sell the right to litigate it for a price to another person.

Background facts:

The basic facts of this case were that people were given wrong financial advice by West Bom Building Society – they basically took money out of their money and invested it in bonds/the stock market. When a recession struck these people lost a lot of money. These people then sought to assign their claim to the Investors Compensation scheme (ICS), but there was a non-assignation clause in their contract.

Judgment:

The Court held that this prevented the ICS from being able to sue them because they were not the original person with the claim.

Ratio-decidendi:

‘In the Court of Appeal, Leggatt L.J. said that the judge's interpretation was "not an available meaning of the words." "Any claim (whether sounding in rescission for undue influence or otherwise)" could not mean "Any claim sounding in rescission (whether for undue influence or otherwise)" and that was that. He was unimpressed by the alleged commercial nonsense of the alternative construction. My Lords, I will say at once that I prefer the approach of the learned judge. But I think I should preface my explanation of my reasons with some general remarks about the principles by which contractual documents are nowadays construed. I do not think that the fundamental change which has overtaken this branch of the law, particularly as a result of the speeches of Lord Wilberforce in Prenn v Simmonds [1971] 1 WLR 1381, 1384-1386 and Reardon Smith Line Ltd v Yngvar Hansen-Tangen [1976] 1 WLR 989, is always sufficiently appreciated. The result has been, subject to one important exception, to assimilate the way in which such documents are interpreted by judges to the common sense principles by which any serious utterance would be interpreted in ordinary life. Almost all the old intellectual baggage of "legal" interpretation has been discarded. The principles may be summarised as follows: (1) Interpretation is the ascertainment of the meaning which the document would convey to a reasonable person having all the background knowledge which would reasonably have been available to the parties in the situation in which they were at the time of the contract. (2) The background was famously referred to by Lord Wilberforce as the "matrix of fact," but this phrase is, if anything, an understated description of what the background may include. Subject to the requirement that it should have been reasonably available to the parties and to the exception to be mentioned next, it includes absolutely anything which would have affected the way in which the language of the document would have been understood by a reasonable man. (3) The law excludes from the admissible background the previous negotiations of the parties and their declarations of subjective intent. They are admissible only in an action for rectification. The law makes this distinction for reasons of practical policy and, in this respect only, legal interpretation differs from the way we would interpret utterances in ordinary life. The boundaries of this exception are in some respects unclear. But this is not the occasion on which to explore them. (4) The meaning which a document (or any other utterance) would convey to a reasonable man is not the same thing as the meaning of its words. The meaning of words is a matter of dictionaries and grammars; the meaning of the document is what the parties using those words against the relevant background would reasonably have been understood to mean. The background may not merely enable the reasonable man to choose between the possible meanings of words which are ambiguous but even (as occasionally happens in ordinary life) to conclude that the parties must, for whatever reason, have used the wrong words or syntax. (see Mannai Investments Co Ltd v Eagle Star Life Assurance Co Ltd [1997] 2 WLR 945. (5) The "rule" that words should be given their "natural and ordinary meaning" reflects the common sense proposition that we do not easily accept that people have made linguistic mistakes, particularly in formal documents. On the other hand, if one would nevertheless conclude from the background that something must have gone wrong with the language, the law does not require judges to attribute to the parties an intention which they plainly could not have had. Lord Diplock made this point more vigorously when he said in The Antaios Compania Neviera SA v Salen Rederierna AB [1985] 1 AC 191, 201: "... if detailed semantic and syntactical analysis of words in a commercial contract is going to lead to a conclusion that flouts business commonsense, it must be made to yield to business commonsense”’, Lord Hoffman.

'(1) meaning ... the document would convey to a reasonable person ... (2) ... matrix of fact ... (3) the law ... excludes previous negotiations ... for ... legal interpretation ... (4) ... not a matter of dictionaries and grammar ... the meaning of a document is what the parties using those words against the relevant background would have been reasonably understood to mean ... (5) words ... natural and ordinary meaning ... we do not easily accept that people have made linguistic mistakes... if one would nevertheless conclude from the background that something must have gone wrong with the language, the law does not attribute to the parties an intention which they plainly could not have made', Lord Hoffman, 107.

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.