Hastings v Finsbury Orthopaedics Ltd & Anor (Scotland) [2022] UKSC 19 (29 June 2022)

Citation:Hastings v Finsbury Orthopaedics Ltd & Anor (Scotland) [2022] UKSC 19 (29 June 2022).

Subjects invoked: 22. 'Product liability'.

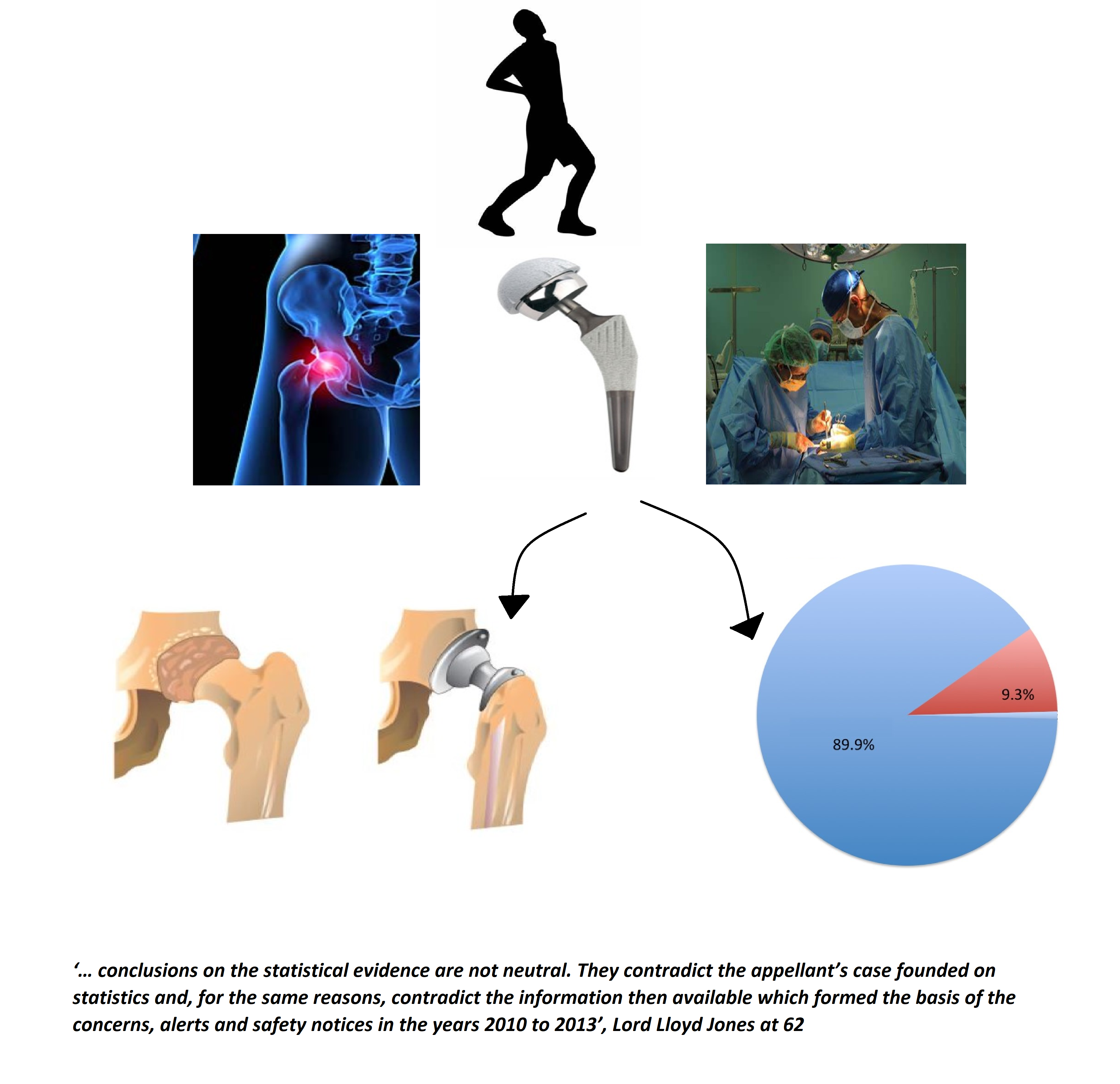

Rule of thumb:Are some products so inherently dangerous they should never have been released? Are metal hip replacements device considered ‘inherently defective’ products which patients are automatically entitled to damages for? No. Metal hip replacements are considered to be ‘risky’ products. However, ‘risky’ products, which people are well warned about, are not automatically ‘defective’. Metal hip replacements do not have a particularly high rate of success, hence why the overwhelming majority of surgeons do not use or recommend them, however, they do work well for some patients, and their percentage success statistics are not so low that they are automatically considered to be defective.

Background facts:

This case was in the subject of product liability. It invoked the principles of ‘risky products’, and ‘inherently defective’ products – the pursuer, Hastings, was arguing that metal hip replacements were ‘inherently defective’ entitling him to damages, but the defenders, Finsbur Orthopaedics, were arguing that they were only ‘risky’, which they warned about, meaning that there was no entitlement to damages.

The material facts of this case were that a new hip-replacement treatment was innovated, which was called ‘metal-on-metal’ hip replacements. This in theory allowed people to have hip replacements that gave them greater stability. ‘Metal-on-metal’ hip replacements had limited real-life testing of them done on them as people and the initial results were fairly promising. Finsbury therefore brought out this product and attached a significant warning on it declaring it as a ‘risky’ products. Hastings, the pursuer in this case, got this ‘metal-on-metal’ hip replacement operation. Hastings began the rehabilitation period for it, but it became clear after a period that it was not successful. This naturally caused Hastings a serious amount of pain, suffering, debilitation and inconvenience. Physicians in hospitals raised concerns about the large number of patients that were not having a high enough level of success with this ‘metal-on-metal’ hip replacement treatment either. Larger amounts of data began to show that the success with the ‘metal-on-metal’ hip replacements was generally low for people meaning that it was a very risky product, with it having a failure rate of 10.7% at the 4 year-mark. Despite this relatively low rate of success, the statistics were mixed. Many people reported that the metal-on-metal hip replacement was a resounding success for them, it was life-changing for them, and that they were absolutely delighted with it. With this additional data, despite it being successful for many people, the Finsbury Orthopaedics Ltd issued severe warnings to all hospitals/surgeons who had bought their products as the failure statistics at the 4 year mark were not good enough. Finsbury Orthopaedics also decided to stop selling these ‘hip-on-hip’ products because of the low rate of success it had and the damage it did commercially to their brand.

Hastings sued Finsbury Orthopaedics Ltd and another. Hastings argued that metal hip replacements were ‘inherently defective’ due to the 11% failure rate at the 4 year mark. Hastings further argued that the warnings to physicians combined with the removal of the product from the market were admissions of liability by Finsbury that the ‘metal-on-metal’ hip replacements were ‘defective’, thereby giving him a right to damages for the damage caused to him by the product. Finsbury Orthopaedics Ltd argued that these products were not inherently defective. They argued that the statistics agreed upon were not at such a high failure to reach the point of being deemed to be inherently defective. Finsbury further explained that there was no inherent design flaw, and they worked extremely well for some people.

Judgment:

The Court upheld the arguments of the Finsbury Orthopaedics Ltd and another. The Court essentially held that this case revolved around the expert statistical evidence, which Hastings did not dispute. The Court held that a 10-11% failure rate at the 4 year mark was not a sufficiently high enough failure rate for the metal hip replacements to be considered inherently defective. Hastings was not entitled to damages from Finsbury for his metal hip not working.

Ratio-decidendi:

‘60. Once again it is clear that the reason for the FSN and the basis on which it was issued was the statistic that in the case of the MITCH-Accolade product the revision rate was 10.67% at four years. 61. On their face, these notices and the statistics on which they were based appear to support the existence of a failure to meet the standard of the applicable entitled expectation. As matters stood in 2012 it was clearly necessary for the MHRA and the respondents to issue these notices. In the case of the respondents, it was also a commercially prudent step to issue the FSN, notwithstanding the fact that the MITCH-Accolade product was no longer being marketed. However, these notices and statistics cannot of themselves be determinative of the issue whether there was a breach of an entitled expectation. In assessing whether there has been compliance with an entitled expectation the court is entitled and required to have regard to material available at the time of proof which was not available in 2012 when the notices were issued. By the time of proof in 2019 there was in evidence before the Outer House a statistical analysis by Professor Platt which was not contested by the appellant. The prima facie evidence provided by the notices must now be examined in the light of such of the conclusions of Professor Platt as were accepted by the Lord Ordinary. 62. The reasoning, summarised earlier in this judgment, which led Professor Platt to the conclusion that the appellant’s case of a breach of entitled expectation was not made out on a statistical basis, applies equally to this category of prima facie evidence. Contrary to the submission on behalf of the appellant, the Lord Ordinary’s conclusions on the statistical evidence are not neutral. They contradict the appellant’s case founded on statistics and, for the same reasons, contradict the information then available which formed the basis of the concerns, alerts and safety notices in the years 2010 to 2013. Professor Platt’s evidence does not leave this category of prima facie evidence unchallenged; on the contrary it undermines it. … conclusions on the statistical evidence are not neutral. They contradict the appellant’s case founded on statistics and, for the same reasons, contradict the information then available which formed the basis of the concerns, alerts and safety notices in the years 2010 to 2013’, Lord Lloyd Jones

Other useful quotes:

‘22. At proof, the respondents relied upon evidence of biostatistics from Professor Robert Platt, Professor of Pharmacoepidemiology at McGill University, Canada. The appellant agreed that Professor Platt’s evidence was unchallenged and his attendance for cross-examination was not required. The appellant did not seek to call his own expert evidence on statistics. Furthermore, the parties were agreed that Professor Platt’s evidence demonstrated that there was no reliable statistical evidence that the revision rate of the MITCH-Accolade product was out of line with the relevant benchmarks. 23. The Guidance issued in 2000 by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (“NICE”) stated that the best prostheses had a revision rate of 10% or less at ten years and that this should be regarded as the benchmark in the selection of prostheses for primary THR. A product would satisfy this benchmark if the 95% confidence interval of the Kaplan-Meier cumulative revision rates estimate for the relevant product included the benchmark revision rate. The UK Orthopaedic Data Evaluation Panel (“ODEP”) considered ten year outcome data to be the relevant minimum benchmark, and to characterise a THR product as “Class A”, ODEP required a revision rate of 3% or less at three years, 5% or less at five years, 7% or less at seven years and 10% or less at ten years. Again, under the ODEP approach, a product satisfied the NICE Guidance if the 95% confidence interval of the Kaplan-Meier cumulative revision rate estimate for the product included the benchmark revision rate. 24. The Medical Device Alert (“MDA”) issued in April 2012 in respect of the MITCH-Accolade product had stated a revision rate of 10.7% at four years. Professor Platt provided an analysis based on data recorded in the UK National Joint Registry (the “NJR”) which showed a revision probability for the MITCH-Accolade product of 23.2% (95% CI 18.4-28.9%) at ten years, which was significantly worse than those for other prostheses. However, Professor Platt concluded that the use of the NJR data as a measure of survivorship would create a misleading impression for a number of reasons’.

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.