R v Gough, [1993] UKHL 1

Citation:R v Gough, [1993] UKHL 1

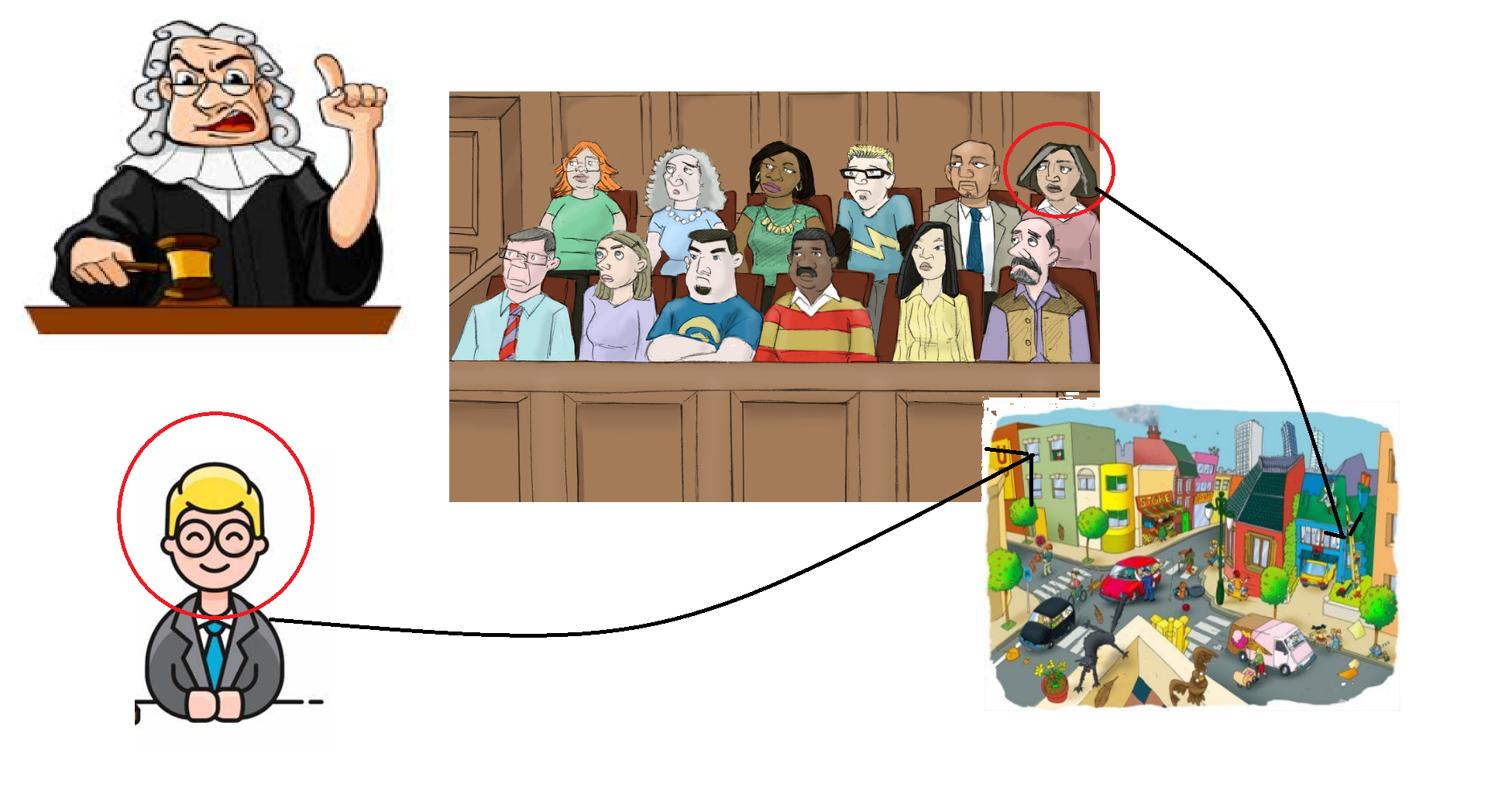

Rule of thumb:If a juror lives in the same neighbourhood as an accused person, are they fit to be a juror in the case? Generally, yes, they are, however, it is not recommended.

Background facts:

The basic facts of this case were that a juror was on a jury where Gough was convicted. As the verdict was being read out, one of the jurors noticed one of her close-by neighbours in the gantry, and noticed that this neighbour was being aggressively with the verdict. The juror later discovered that the accused was potentially her neighbour as well – although she did not know this before the verdict was considered. The Court was asked to consider whether there should be a retrial on this basis.

Judgment:

The Court held that there should not be as it was held that in order for there to be a retrial there had to be a ‘real danger of bias’ – rather than just justice having to appear fully to be done which was a lesser standard – and in this case there was deemed to be no real danger of injustice. This same standard was held to be the case magistrates as well as inferior tribunals and arbitrations.

Ratio-decidendi:

‘Finally, for the avoidance of doubt, I prefer to state the test in terms of real danger rather than real likelihood, to ensure that the court is thinking in terms of possibility rather than probability of bias. Accordingly, having ascertained the relevant circumstances, the court should ask itself whether, having regard to those circumstances, there was a real danger of bias on the part of the relevant member of the tribunal in question, in the sense that he might unfairly regard (or have unfairly regarded) with favour, or disfavour, the case of a party to the issue under consideration by him... After all it is alleged that, for example, a justice or a juryman was biased, i.e. that he was motivated by a desire unfairly to favour one side or to disfavour the other. Why does the court not simply decide whether that was in fact the case? The answer, as always, is that it is more complicated than that. First of all, there are difficulties about exploring the actual state of mind of a justice or juryman. In the case of both, such an inquiry has been thought to be undesirable: and in the case of the juryman in particular, there has long been an inhibition against, so to speak, entering the jury room and finding out what any particular juryman actually thought at the time of decision. But there is also the simple fact that bias is such an insidious thing that, even though a person may in good faith believe that he was acting impartially, his mind may unconsciously be affected by bias.... the approach... to look at the relevant circumstances and to consider whether there is such a degree of possibility of bias that the decision in question should not be allowed to stand’, Lord Goff

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.