R v Horseferry Magistrates’ Court, ex p Bennett 1994, 1 AC 42 (HL)

Citation:R v Horseferry Magistrates’ Court, ex p Bennett 1994, 1 AC 42 (HL)

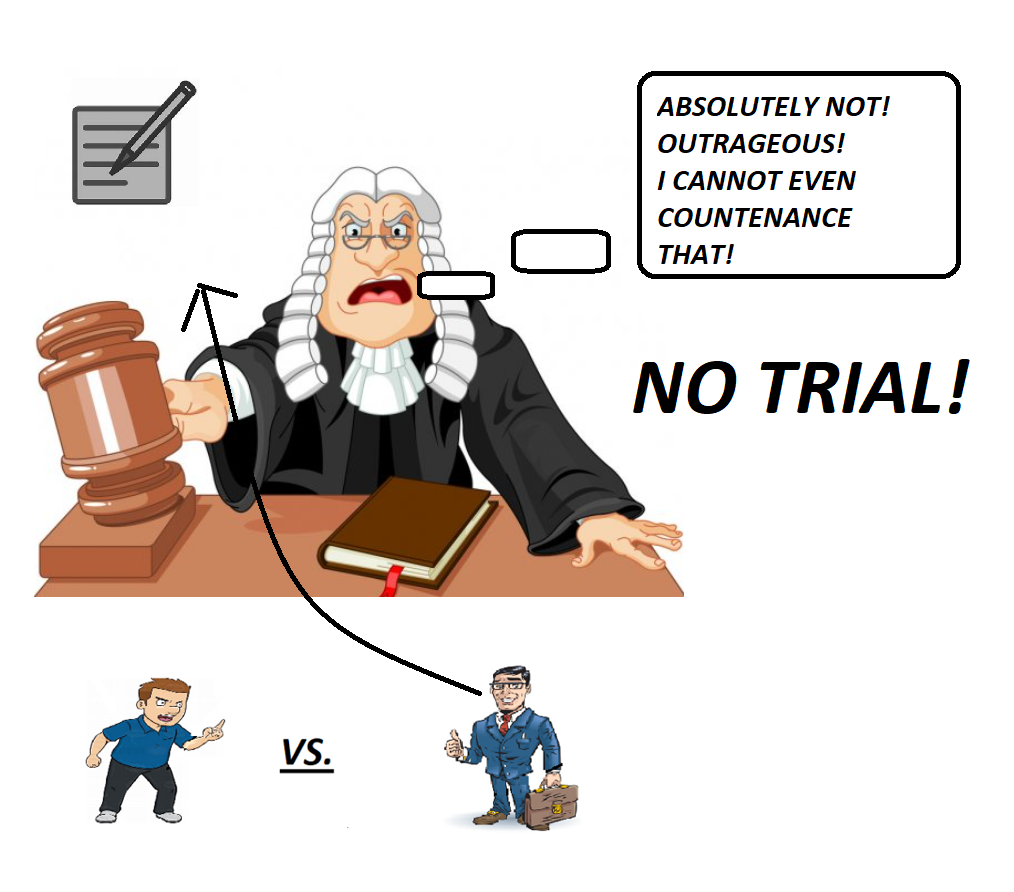

Rule of thumb:If a person is behaving scandalously in legal process or making arguments to the Court that scandalous behaviour is legal, can the full trial go ahead? No, where a person has behaved scandalously in legal process, or, is making arguments that scandalous behaviour causing public outrage is legal then the Court should not countenance these legal arguments & not allow the case to proceed to trial.

Background facts:

The facts of this case were that Mr Bennett was accused of a crime in the UK. He was essentially kidnapped/forced roughshod into the UK without a fair and proper extradition process from the country he was in previously.

Judgment:

The Court refused to let the criminal trial go ahead for various reasons in these circumstances. They held that this was an abuse of Court procedure. They further stated that it offended against the comity of law principle in respecting the rule of law in other countries. They also held that this trial process would be tainted by this.

It should be noted that Lord Oliver dissented – Lord Oliver argued that the seriousness of the crime and the public interest outweighed the laws which had been breached in bringing Oliver to the UK – this has opened the door to this matter being argued again if a similar process is followed but it involves an utterly heinous crime. The Court further held the general point that where a criminally accused person is given ‘immunity’ from the prosecution and the police, they cannot go back on this promise.

Ratio-decidendi:

‘There is, I think, no principle more basic to any proper system of law than the maintenance of the rule of law itself. When it is shown that the law agency responsible for bringing a prosecution has only been enabled to do so by participating in violations of international law and the laws of another state in order to secure the presence of the accused within the territorial jurisdiction of the Court, I think that respect for the rule of law demands that the Court take cognisance of that circumstance. To hold that the Court may turn a blind eye to executive lawlessness beyond the frontiers of its own jurisdiction is, to my mind, an insular and unacceptable view. Having taken cognisance of the lawlessness it would again appear to me to be a wholly inadequate response for the Court to hold that the only remedy lies in civil proceedings at the suit of the defendant... Since the prosecution could never have been brought if the defendant had not been illegally abducted, the whole proceeding is tainted’. Lord Bridge, ‘the court, in order to protect its own process from being degraded and misused, must have the power to stay proceedings which have come before it and have only been made possible by acts which offend the court’s conscience as being contrary to the rule of law. Those acts by providing a morally unacceptable foundation for the exercise of jurisdiction over the suspect taint the proposed trial and, if tolerated, will mean that the court’s process has been abused… It would, I submit, be generally conceded that for the Crown to go back on a promise of immunity given to an accomplice who is willing to give evidence against his confederates would be unacceptable to the proposed court of trial, although the trial itself could be fairly conducted’, Lord Lowry, ‘‘It would, I submit, be generally conceded that for the Crown to go back on a promise of immunity given to an accomplice who is willing to give evidence against his confederates would be unacceptable to the proposed court of trial, although the trial itself could be fairly conducted’, ‘Your Lordships are now invited to extend the concept of abuse of process a stage further. In the present case there is no suggestion that the appellant cannot have a fair trial, nor could it be suggested that it would have been unfair to try him if he had been returned to this country through extradition proceedings. If the court is to have the power to interfere with the prosecution in the present circumstances it must be because the judiciary accept a responsibility for the maintenance of the rule of law which embraces a willingness to oversee executive action and to refuse to countenance behaviour that threatens either basic human rights or the rule of law. My Lords, I have no doubt that the judiciary should accept this responsibility in the field of criminal law. The great growth of administrative law during the latter half of this century has occurred because of the recognition by the judiciary and Parliament alike that it is the function of the High Court to ensure that executive action is exercised responsibly and as Parliament intended. So also should it be in the field of criminal law and if it comes to the attention of the court that there has been a serious abuse of power it should, in my view, express its disapproval by refusing to act upon it. . . The courts, of course, have no power to apply direct discipline to the police or the prosecuting authorities, but they can refuse to allow them to take advantage of abuse of power by regarding their behaviour as an abuse of process and thus preventing a prosecution’, Lord Griffiths

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.