O’Reilly v Mackman [1983] UKHL 1

Citation:O’Reilly v Mackman [1983] UKHL 1

Rule of thumb:If a public authority breaches a public-services statute can you obtain damages? As a general rule, no – it is only if there is no statute and they have breached the common law then damages can be sued for. This is a seminal case and ratio-decidendi in administrative law. This case affirmed that if there is a public servant/Minister acting under prerogative, with no underpinning statute which relates to it & only the common law applying to them, then they can be sued in ordinary Courts for the typical private law remedies of declaration, financial damages, and injunction, however, if they are being sued for a breach of an act/statutory duty, then the more typical Judicial review/public law remedies of ‘mandamus, certiorari, prohibition’ (quashing, commanding, prohibiting), would apply to this, and they can only be sued via judicial review rather than in the ordinary civil Court. This is why a lot of the laws involving the public authorities are put on a statutory basis as it makes it harder for them to be sued for damages.

Background facts:

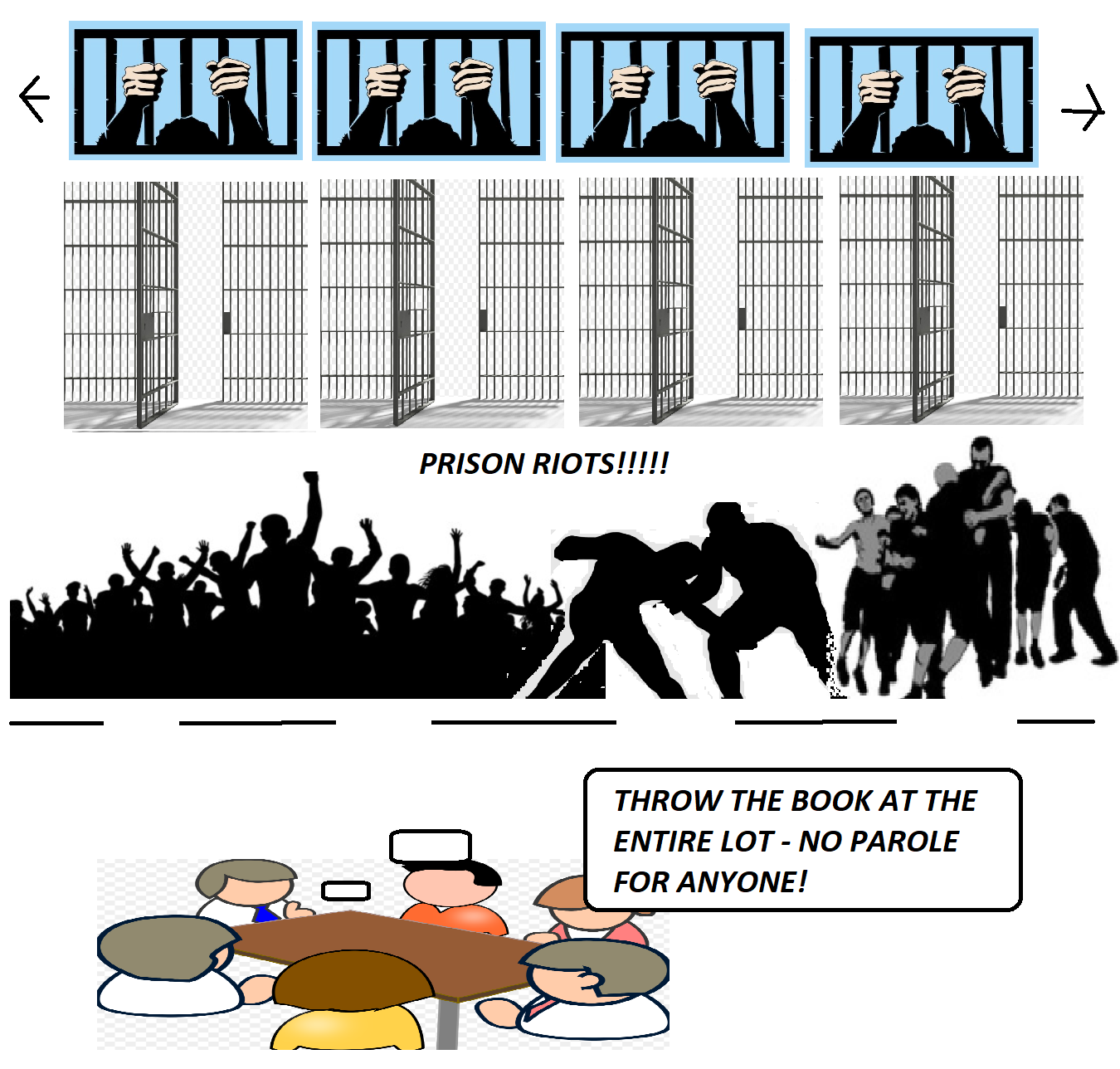

The basic facts were that was a riot in the prison. Across the board everyone who was involved all had opportunities for early release cancelled. The prisoners tried to sue the prison authorities for failure to give them all due process in the ordinary Courts.

Judgment:

The Court held that early release from a prison sentence was a public law matter which could not be litigated in the private Courts. They affirmed that a prisoner did have the right to challenge this being done to them via judicial review.

Ratio-decidendi:

‘In modern times we have come to recognise two separate fields of law: one of private law, the other of public law. Private law regulates the affairs of subjects as between themselves. Public law regulates the affairs of subjects vis-à-vis public authorities. For centuries there were special remedies available in public law. They were the prerogative writs of certiorari, mandamus and prohibition. As I have shown, they were taken in the name of the sovereign against a public authority which had failed to perform its duty to the public at large or had performed it wrongly. Any subject could complain to the sovereign: and then the King's courts, at their discretion, would give him leave to issue such one of the prerogative writs as was appropriate to meet his case. But these writs, as their names show, only gave the remedies of quashing, commanding or prohibiting. They did not enable a subject to recover damages against a public authority, nor a declaration, nor an injunction. This was such a defect in public law that the courts drew upon the remedies available in private law - so as to see that the subject secured justice. It was held that, if a public authority failed to do its duty and, in consequence, a member of the public suffered particular damage therefrom. he could sue for damages by an ordinary action in the courts of common law: Likewise, if a question arose as to the rights of a subject vis-à-vis the public authority, he could come to the courts and ask for a declaration...’ Lord Denning (Court of Appeal before the matter went to the House of Lords) ‘[It would...] as a general rule be contrary to public policy, and as such an abuse of the process of the court, to permit a person seeking to establish that a decision of a public authority infringed rights to which he was entitled to protection under public law to proceed by way of ordinary authorities (private law)...’, Lord Diplock

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.