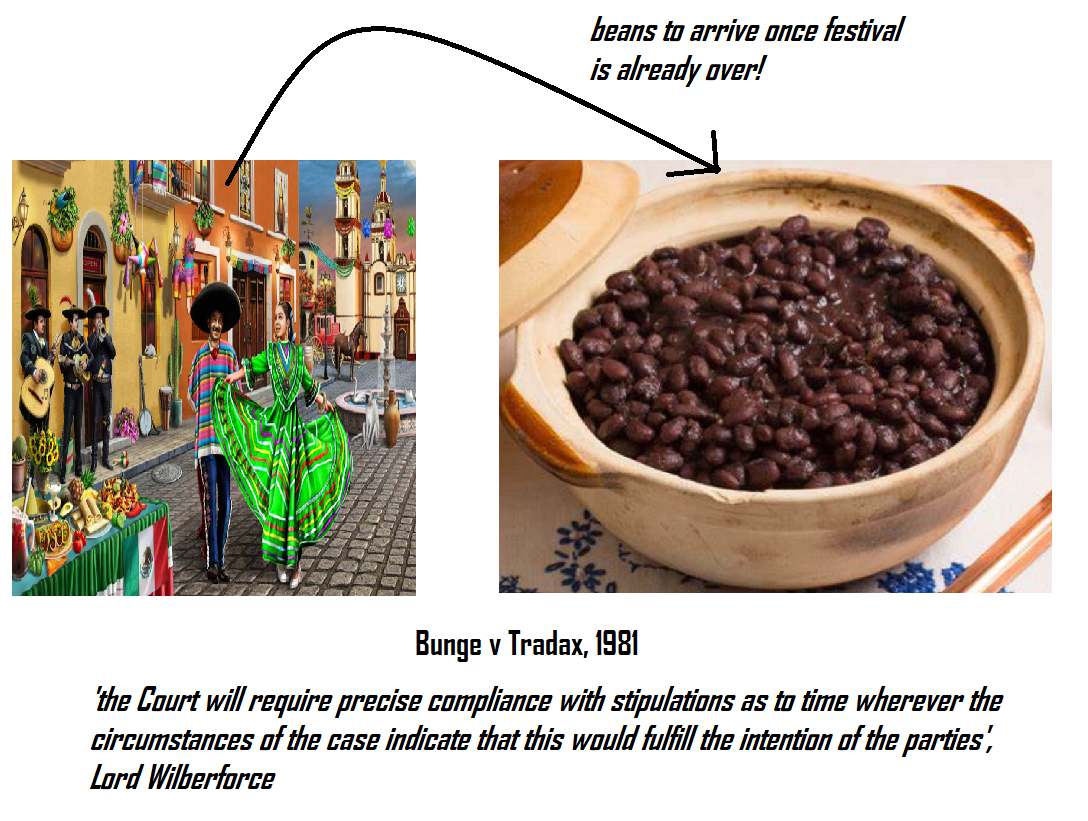

Bunge Corporation v Tradax Export SA Panama [1981] UKHL 11

Citation:Bunge Corporation v Tradax Export SA Panama [1981] UKHL 11

Rule of thumb:Where one party informs the other that ‘time is of the essence’ in the contract, is a slight delay a material breach of contract bringing it to an end with no further obligations? Yes, failure to comply with a ‘time of the essence’ term is a material breach entitling the other party to rescind.

Background facts:

The facts of this case were that soya beans had been agreed to be purchased and delivered to Mexico for a certain date but these were 4 days late for loading onto the ship. The soya beans had to be at the location for this date to coincide with market conditions at this date - Mexican festival celebrations. When they were 4 days late the market conditions had passed meaning that the beans were no longer needed and were no longer nearly as valuable in Mexico.

Parties argued:

The buyers in this case argued that the exporters were in fundamental breach of a material condition and so refused to pay or take delivery late. The sellers argued that the reasons for the delay were caused by factors outwith their control and this was well-established not to be a fundamental condition. The buyers responded that they clearly stated in the contract that 'time was of the essence' thereby making this a condition rather than a warranty.

Judgment:

The Court upheld the arguments of the buyers and they did not have to pay for the beans. Where a contract is a 'time is of the essence' contract then failure to adhere to this term is deemed to a be a fundamental breach of a material condition.

Ratio-decidendi:

'the Court will require precise compliance with stipulations as to time wherever the circumstances of the case indicate that this would fulfill the intention of the parties', Lord Wilberforce

‘In conclusion, the statement of the law in Halsbury's Laws of England, 4th Ed. Vol. 9 (Contract) paragraphs 481-2, including the footnotes to paragraph 482 (generally approved in the House in the United Scientific Holdings case), appears to me to be correct, in particular in asserting (1) that the court will require precise compliance with stipulations as to time wherever the circumstances of the case indicate that this would fulfil the intention of the parties, and (2) that broadly speaking time will be considered of the essence in " mercantile" contracts—with footnote reference to authorities which I have mentioned (summarised quote of Lord Wilberforce), ‘The test suggested by the appellants was a different one. One must consider, they said, the breach actually committed and then decide whether that default would deprive the party not in default of substantially the whole benefit of the contract. They invoked even certain passages in the judgment of Diplock L.J. in Hong Kong Fir to support it. One may observe in the first place that the introduction of a test of this kind would be commercially most undesirable. It would expose the parties, after a breach of one, two, three, seven and other numbers of days to an argument whether this delay would have left time for the seller to provide the goods. It would make it, at the time, at least difficult, and sometimes impossible, for the supplier to know whether he could do so. It would fatally remove from a vital provision in the contract that certainty which is the most indispensable quality of mercantile contracts, and lead to a large increase in arbitrations. It would confine the seller—perhaps after arbitration and reference through the courts—to a remedy in damages which might be extremely difficult to quantify. These are all serious objections in practice. But I am clear that the submission is unacceptable in law. The judgment of Diplock LJ does not give any support and ought not to give any encouragement to any such proposition; for beyond doubt it recognises that it is open to the parties to agree that, as regards a particular obligation, any breach shall entitle the party not in default to treat the contract as repudiated. Indeed, if he were not doing so he would, in a passage which does not profess to be more than clarificatory, be discrediting a long and uniform series of cases—at least from Bowes v Shand (1877) 2 App. Cas. 455 onwards which have been referred to by my noble and learned friend. Lord Roskill. It remains true, as Lord Roskill has pointed out in Cehave NV v Bremer Handelsgesellschaft mbH [1976] 1 Q.B. 44, that the courts should not be too ready to interpret contractual clauses as conditions. And I have myself commended, and continue to commend, the greater flexibility in the law of contracts to which Hong Kong Fir points the way (Reardon Smith Line Ltd v Hansen-Tangen [1976] 1 W.L.R. 989, 998). But I do not doubt that, in suitable cases, the courts should not be reluctant, if the intentions of the parties as shown by the contract so indicate, to hold that an obligation has the force of a condition, and that indeed they should usually do so in the case of time clauses in mercantile contracts. To such cases the "gravity" of the breach " approach of Hong Kong Fir would be unsuitable. I need only add on this point that the word " expressly " used by Diplock LJ at p.70 of his judgment in Hong Kong Fir should not be read as requiring the actual use of the word " condition ": any term or terms of the contract, which, fairly read, have the effect indicated, are sufficient. Lord Diplock himself has given recognition to this in this House (Photo Production Ltd v Securicor Transport Ltd [I980] A.C. 827, 849). I therefore reject that part of the appellant's argument which was based upon it, and I must disagree with the judgment of the learned trial judge in so far as he accepted it. I respectfully endorse, on the other hand, the full and learned treatment of this issue in the judgment of Megaw L.J. in the Court of Appeal... In conclusion, the statement of the law in Halsbury's Laws of England, 4th Ed. Vol. 9 (Contract) paragraphs 481-2, including the footnotes to paragraph 482 (generally approved in the House in the United Scientific Holdings case), appears to me to be correct, in particular in asserting (1) that the court will require precise compliance with stipulations as to time wherever the circumstances of the case indicate that this would fulfil the intention of the parties, and (2) that broadly speaking time will be considered of the essence in " mercantile" contracts—with footnote reference to authorities which I have mentioned’, Lord Wilberforce.

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.