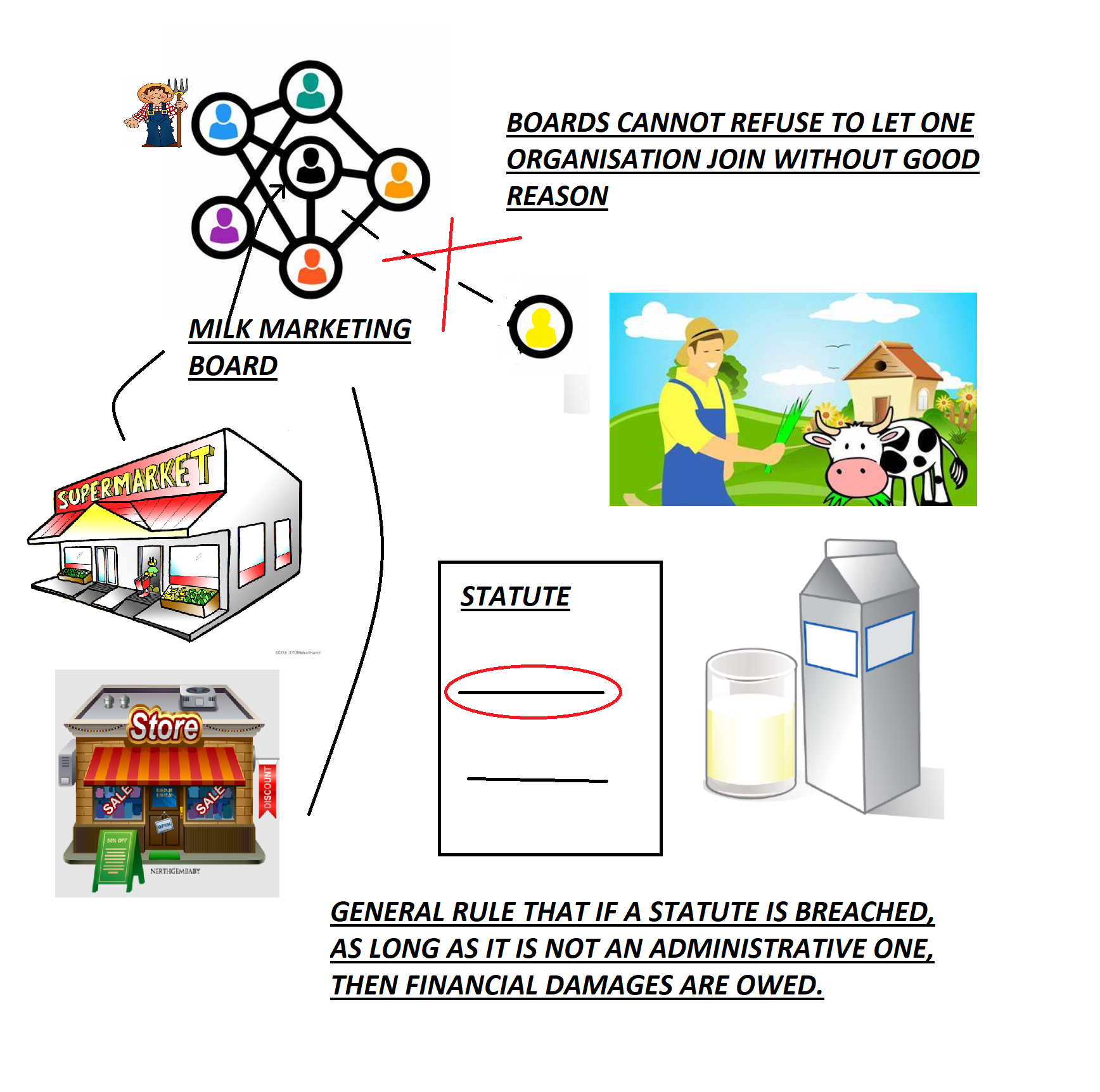

Garden Cottage Foods v Milk Marketing Board, 1984 UKHL

Citation:Garden Cottage Foods v Milk Marketing Board, 1984 UKHL

Rule of thumb:If you can prove another person has breached a statute, what is the Court supposed to do? Where a person has breached a statute towards you, the general rule is that the Court is expected to pay you damages. This case affirmed the fundamental principle that if one party breaches a statute, and another person sustains damages as a result of this, then they are entitled to financial compensation for this, unless it is a statute for the performance of public services or it is expressly stated under statute that they are not entitled to damages.

Rule of thumb:If there is a dominant company in the market refusing to enter a contract with you so you cannot trade, what can you do? This is a breach of the competition law ‘refusal to supply’ doctrine and they either have to enter into a contract with you or pay you damages.

Background facts:

The basic facts of this case were that the Milk Marketing Board had a dominant position in the market in the supply of butter. They refused to deal with Garden Cottage Foods.

Judgment:

The Court held that this entitled Garden Cottage to an interim injunction to uphold the status quo until the matter was considered more fully, and potentially damages as well. This is often associated with the cases that ensured ‘privatisation of competition law’ as people breaching it could owe damages to others for it.

Ratio-decidendi:

‘... I, for my own part, find it difficult to see how it can ultimately be successfully argued that a contravention of Article 86 which causes damage to an individual citizen does not give rise to a cause of action in English law of the nature of cause of action for breach of statutory duty...’, ‘that if such a contravention of Article 86 gives rise to any cause of action at all, it gives rise to a cause of action for which there is no remedy in damages to compensate for loss already caused by that contravention but only a remedy by way of injunction to prevent future loss being caused… A cause of action to which an unlawful act by the defendant causing pecuniary loss to the plaintiff gives rise, if it possessed those characteristics as respects the remedies available, would be one which, so far as my understanding goes, is unknown in English private law, at any rate since 1875 when the jurisdiction conferred upon the Court of Chancery by Lord Cairns’ Act passed to the High Court. I leave aside as irrelevant for present purposes injunctions granted in matrimonial causes or wardship proceedings which may have no connection with pecuniary loss. I likewise leave out of account injunctions obtainable as remedies in public law, whether upon application for Judicial Review or in an action brought by the Attorney General ex officio or ex relatione some private individual. It is private law, not public law, to which the company has had recourse. In its action it claims damages as well as an injunction. No reasons are to be found in any judgments of the Court of Appeal and none has been advanced at the hearing before your Lordships why in law in logic or in justice if contravention of Article 86 of the Treaty of Rome is capable of giving rise to a cause of action in English private law at all, there is any need to invent a cause of action with characteristics that are wholly novel as respects the remedies that it attracts, in order to deal with breaches of Articles of the Treaty of Rome, which have in the United Kingdom the same effect as statutes’, ‘The status quo is the existing state of affairs; but since states of affairs do not remain static this raises the query: existing when? In my opinion, the relevant status quo to which reference was made in American Cyanamid is the state of affairs existing during the period immediately preceding the issue of the writ claiming the permanent injunction or, if there be unreasonable delay between the issue of the writ and the motion for an interlocutory injunction, the period immediately preceding the motion. The duration of that period since the state of affairs last changed must be more than minimal, having regard to the total length of the relationship between the parties in respect of which the injunction is granted; otherwise the state of affairs before the last change would be the relevant status quo’, Lord Diplock

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.