Bushell v Secretary of State for the Environment [1980] UKHL 1

Citation:Bushell v Secretary of State for the Environment [1980] UKHL 1

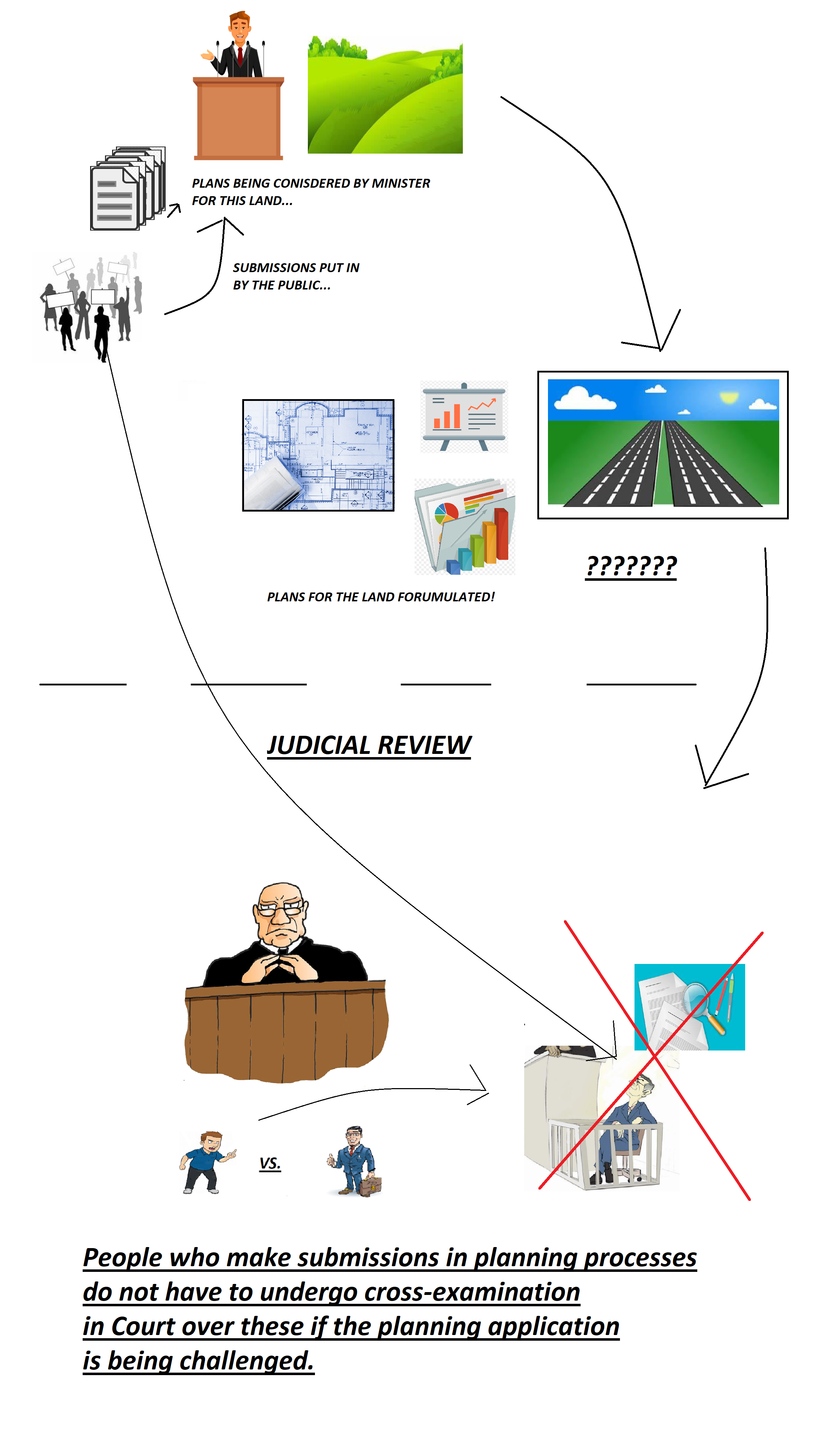

Rule of thumb:When planning applications are being made, does there have to be the opportunity for cross-examination on all the reports and submissions made? No, this Court-style assessment of all the evidence put into planning applications would be too slow and expensive – there just has to be basic fairness & consideration rather than extension consideration of every piece of evidence submitted.

Background facts:

The basic facts of this case were that there was an application for an extension of the M40. Various submissions were made during the planning process before work commenced. The environment secretary relied heavily on an expert report which was believed by Bushell to lack credibility.

Parties argued:

Bushell sought the right to cross examine the expert who provided this to show the evidence they provided was very unreliable.

Judgment:

The Court held that during the planning process there was no right to cross examine experts who had provided reports – it was the traditional approach where planning decisions could only be rejected based on the traditional grounds. The Court in this case held that there is no one-size fits all approach to be taken to infrastructure planning – there is the general right that all material points should be taken into consideration and solid reasons provided for decisions, but it is important not to be overly knit-picky about small individual featurrs – what is important is to make an acceptable decision, not a great decision.

Ratio-decidendi:

‘What is a fair procedure to be adopted at a particular inquiry will depend upon the nature of its subject matter’. (Lord Diplock)

‘The Minister has to balance his duties to the public in general against the interests of the objectors. There may be circumstances in which the emergence of fresh evidence would as a matter of justice demand the re-opening of an inquiry, circumstances in which no reasonable Minister would fail to re-open it. There is no doubt in my mind that this is very far from being such a case’. (Lord Lane)

‘What is a fair procedure to be adopted at a particular inquiry will depend upon the nature of its subject matter. What is fair procedure is to be judged not in the light of constitutional fictions as to the relationship between the Minister and the other servants of the Crown who serve in the Government Department of which he is the head, but in the light of the practical realities as to the way in which administrative decisions involving forming judgments based on technical considerations are reached. To treat the Minister in his decision-making capacity as someone separate and distinct from the Department of Government of which he is the political head and for whose actions he alone in constitutional theory is accountable to Parliament, is to ignore not only practical realities but also Parliament's intention. Ministers come and go; departments, though their names may change from time to time, remain. Discretion in making administrative decisions is conferred upon a Minister not as an individual but as the holder of an office in which he will have available to him in arriving at his decision the collective knowledge, experience and expertise of all those who serve the Crown in the department of which, for the time being, he is the political head. The collective knowledge, technical as well as factual, of the civil servants in the Department and their collective expertise is to be treated as the Minister's own knowledge, his own expertise. It is they who in reality will have prepared the draft scheme for his approval; it is they who will in the first instance consider the objections to the scheme and the report of the inspector by whom any local inquiry has been held and it is they who will give to the Minister the benefit of their combined experience, technical knowledge and expert opinion on all matters raised in the objections and the report. This is an integral part of the decision-making process itself; it is not to be equiparated with the Minister receiving evidence, expert opinion or advice from sources outside the Department after the local inquiry has been closed... It is evident that an inquiry of this kind and magnitude is quite unlike any civil litigation and that the inspector conducting it must have a wide discretion as to the procedure to be followed in order to achieve its objectives. These are to enable him to ascertain the facts that are relevant to each of the objections, to understand the arguments for and against them and, if he feels qualified to do so, to weigh their respective merits, so that he may provide the Minister with a fair, accurate and adequate report on these matters...Whether fairness requires an inspector to permit a person who has made statements on matters of fact or opinion, whether expert or otherwise, to be cross-examined by a party to the inquiry who wishes to dispute a particular statement, must depend on all the circumstances. ..Between the black and white of these two extremes, however, there is what my noble and learned friend, Lord Lane, in the course of the hearing described as a " grey area ". Because of the time that must elapse between the preparation of any scheme and the completion of the stretch of motorway that it authorises, the Department, in deciding in what order new stretches of the national network ought to be constructed, has adopted a uniform practice throughout the country of making a major factor in its decision the likelihood that there will be a traffic need for that particular stretch of motorway in fifteen years from the date when the scheme was prepared. This is known as the "design year " of the scheme. Priorities as between one stretch of motorway and another have got to be determined somehow... But schemes authorising the construction of motorways and decisions to act on such authorisations cannot be held up indefinitely because the current methods of estimating and predicting future traffic needs are imperfect and are likely to be improved as further experience is gained. Comparative traffic needs must be measured by the best yardstick available at the time of the decision and it is in the nature of the problem with which the Minister is confronted that this may not be the same at the times when each of the successive decisions are taken: viz. to publish the draft scheme, to make the scheme and to proceed with the construction of the stretch of motorway authorised by the scheme’. (Lord Diplock)

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.