Liverpool City Council v Irwin [1977] AC 239 HL

Citation:Liverpool City Council v Irwin [1977] AC 239 HL

Rule of thumb: .

Background facts:

The facts of this case were that Irwin lived as a tenant in a flat where Liverpool City Council were the landlords. The Council did not maintain parts of the building well – certain parts of it were a mess, and Irwin refused to pay rent until they did so. The Council sought to remove Irwin, and the matter ended up in Court.

Parties argued:

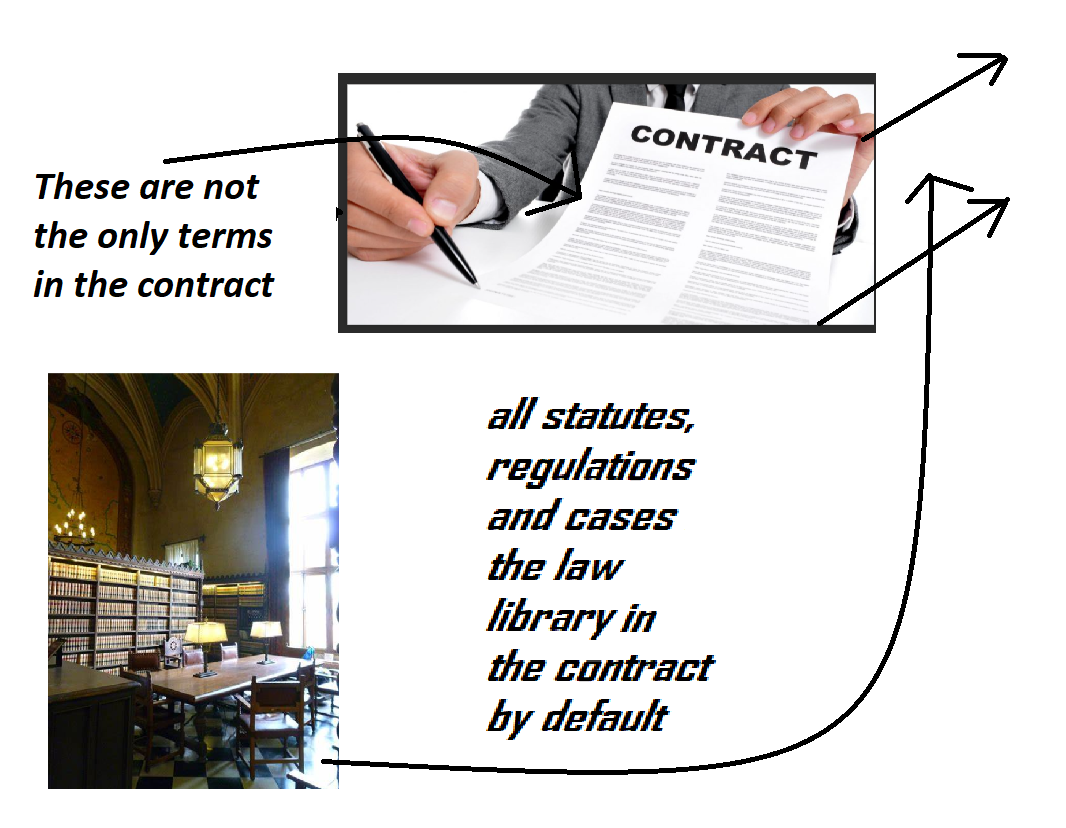

Irwin sought to argue his case based around quoting landlord and tenant Acts as well as past cases, showing that the Council had an obligation to maintain the parts of the building better. The Council sought to argue that none of the past Acts or cases were relevant sources of law to the tenancy agreement with Irwin. The Council argued that the only thing that mattered were the terms of the lease and nothing else. The Council further argued that they had done their level best to maintain the parts of the common area but incessant vandalism and widespread refusal to pay for maintenance by tenants, meant it was impossible for them to maintain the common area.

Judgment:

The Court upheld part of the arguments of Irwin but found in favour of the Council overall. The Court affirmed that all the past Acts and case law Irwin was relying on to make his arguments were valid sources of law - all acts, regulations and case-law precedents are implied terms of the contract. In interpreting these sources and the common law however, the Court held that the Council were not in breach of their duties as landlord. The Court affirmed that where a landlord makes an effort to maintain a close but it is wholly impractical for them to continue doing this due to a widespread reluctance for this amongst tenants, they are under no obligation to maintain the land. Although Irwin had a moral success in his arguments about the implied terms of contracts, Irwin still lost the case overall and had to pay his rent which was in arrera or be evicted from his flat.

Ratio-decidendi:

'it implies a term ... some provision (of statute or common law) is to be implied unless the parties have expressly excluded it ... the Court will (then) ask itself ... the term in question ... reasonable to insert', Lord Cross

‘When it implies a term in a contract the court is sometimes laying down a general rule that in all contracts of a certain type - sale of goods, master and servant, landlord and tenant and so on - some provision is to be implied unless the parties have expressly excluded it. In deciding whether or not to lay down such a prima facie rule the court will naturally ask itself whether in the general run of such cases the term in question would be one which it would be reasonable to insert. Sometimes, however, there is no question of laying down any prima facie rule applicable to all cases of a defined type but what the court is being in effect asked to do is to rectify a particular - often a very detailed - contract by inserting in it a term which the parties have not expressed. Here it is not enough for the court to say that the suggested term is a reasonable one the presence of which would make the contract a better or fairer one; it must be able to say that the insertion of the term is necessary to give - as it is put -'business efficacy' to the contract and that if its absence had been pointed out at the time both parties - assuming them to have been reasonable men - would have agreed without hesitation to its insertion. The distinction between the two types of case was pointed out by Viscount Simonds and Lord Tucker in their speeches in Lister v Romford Ice and Cold Storage Co Ltd [1957] AC 555, 579, 594, but I think that Lord Denning MR in proceeding - albeit with some trepidation - to 'kill off' MacKinnon LJ's 'officious bystander' (Shirlaw v Southern Foundries (1926) Ltd [1939] 2 KB 206, 227) must have overlooked it. Counsel for the appellant did not in fact rely on this passage in the speech of Lord Denning. His main argument was that when a landlord lets a number of flats or offices to a number of different tenants giving all of them rights to use the staircases, corridors and lifts there is to be implied, in the absence of any provision to the contrary, an obligation on the landlord to keep the 'common parts' in repair and the lifts in working order. But, for good measure, he also submitted that he could succeed on the 'officious bystander' test. I have no hesitation in rejecting this alternative submission. We are not here dealing with an ordinary commercial contract by which a property company is letting one of its flats for profit. The respondent council is a public body charged by law with the duty of providing housing for members of the public selected because of their need for it at rents which are subsidised by the general body of ratepayers. Moreover the officials in the council's housing department would know very well that some of the tenants in any given block might subject the chutes and lifts to rough treatment and that there was an ever present danger of deliberate damage by young 'vandals' - some of whom might in fact be children of the tenants in that or neighbouring blocks. In these circumstances, if at the time when the respondents were granted their tenancy one of them had said to the council's representative: 'I suppose that the council will be under a legal liability to us to keep the chutes and the lifts in working order and the staircases properly lighted, 'the answer might well have been - indeed I think, as Roskill LJ thought [1976] QB 319, 338, in all probability would have been - 'Certainly not.' The official might have added in explanation- 'Of course we do not expect our tenants to keep them in repair themselves - though we do expect them to use them with care and to co-operate in combating vandalism. The council is a responsible body conscious of its duty both to its tenants and to the general body of ratepayers and we will always do our best in what may be difficult circumstances to keep the staircases lighted and the lifts and chutes working, but we cannot be expected to subject ourselves to a liability to be sued by any tenant for defects which may be directly or indirectly due to the negligence of some of the other tenants in the very block in question.' Some people might think that it would have been, on balance, wrong for the council to adopt such an attitude, but no one could possibly describe such an attitude as irrational or perverse’, Lord Cross.

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.