Lambert v Lewis [1982] AC 225

Citation:Lambert v Lewis [1982] AC 225

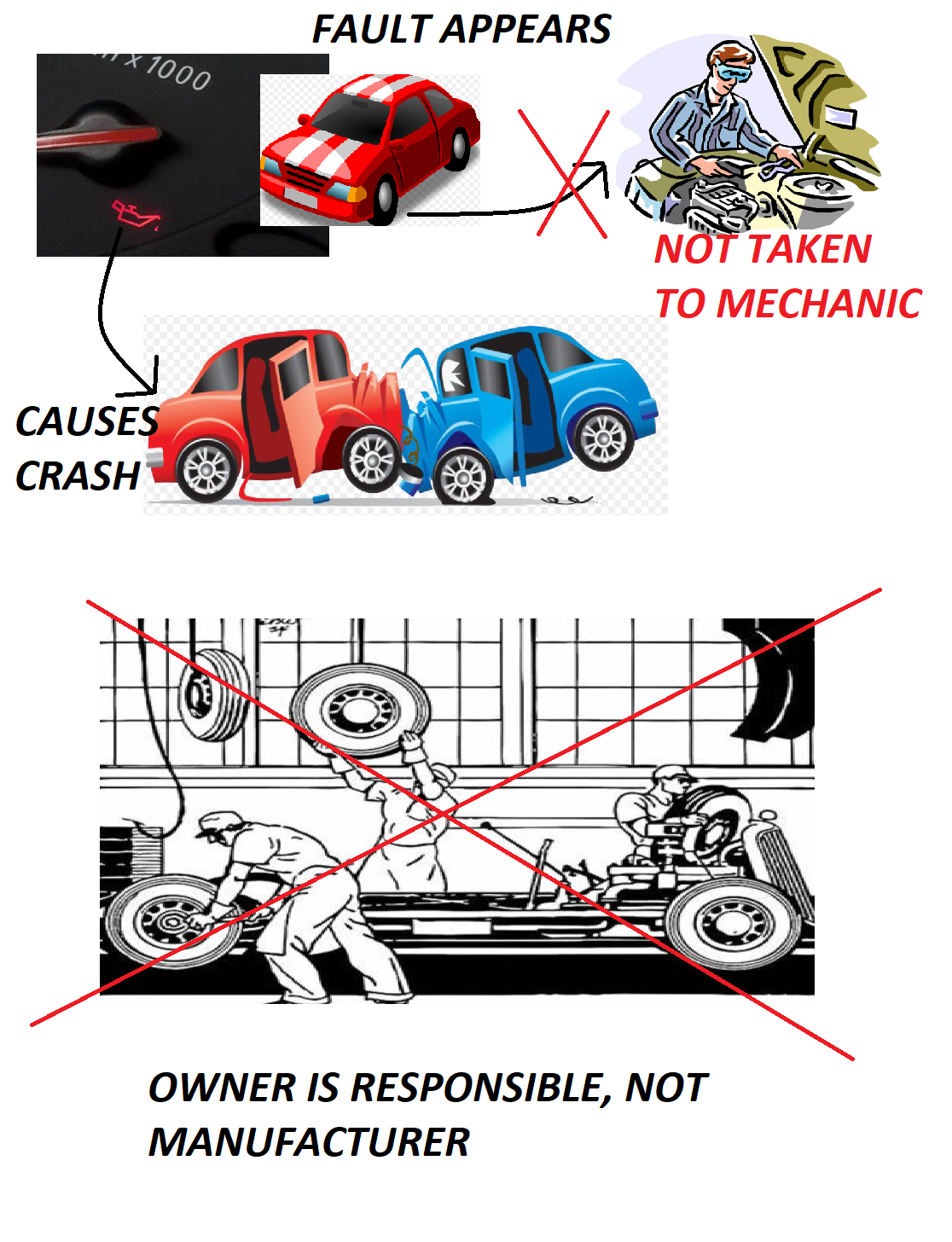

Rule of thumb:Who is liable if a part in a car malfunctions & it causes the car to crash? This case confirmed that if people buy a movable product and it is faulty leading to them experience recurring malfunctions within the warranty period, then they need to inform the manufacturer of these and hand the movable product back to the manufacturer to get fixed. If the purchase of the movable product does not do this, and the product breaks causing damage, the manufacturer is not responsible if they have not been informed about the malfunctions and provided with an opportunity to fix them.

Background facts:The facts of this case were that a farmer bought a trailer for his car. The farmer experienced recurring faults with the trailer connection but kept on with it anyway and hoped it was just ‘teething problems’. The farmer then caused a crash due to the faulty trailer, and the farmer was sued.

Parties argued:The retailer and the manufacturer were brought into the proceedings by the farmer as co-defendants. The farmer argued that he was not liable as this fault existed in the product when he bought it, the product was still under warranty, and he had not overused or misused the product in any way, meaning that his position was that he should not be held liable.

Judgment:

The Court held that the farmer was liable and that he should have informed the manufacturer about the malfunctions and got them fixed. The Court held that the farmer’s co-defendants were not liable for the crash as the faulty trailer was already known about by the farmer.

Ratio-decidendi:

‘I would accept that in the case of the coupling the warranty was still continuing up to the date, some three to six months before the accident, when it first became known to the farmer that the handle of the locking mechanism was missing. Up to that time the farmer would have had a right to rely upon the dealers warranty as excusing him from making his own examination of the coupling to see if it were safe . . After it had become apparent to the farmer that the locking mechanism of the coupling was broken, and consequently that it was no longer in the same state as when it was delivered, the only implied warranty which could justify his failure to take the precaution either to get it mended or at least to find out whether it was safe to continue to use it in that condition, would be a warranty that the coupling could continue to be safely used to tow a trailer on a public highway notwithstanding that it was in an obviously damaged state. My Lords, any implication of a warranty in these terms needs only to be stated, to be rejected . . In the state in which the farmer knew the coupling to be at the time of the accident, there was no longer any warranty by the dealers of its continued safety in use on which the farmer was entitled to rely... The farmer’s liability arose, not from the defective design of the coupling but from his own negligence in failing, when he knew that the coupling was damaged, to have it repaired or to ascertain if it was still safe to use. The issue of causation, therefore, on which the farmer’s claim against the dealers depended, was whether his negligence resulted directly and naturally, in the ordinary course of events from the dealer’s breach of warranty. Manifestly it did not.’ Lord Diplock

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.