Rock Advertising Ltd v MVB Business Exchange Centres Ltd, [2018] UKSC 24

Citation:Rock Advertising Ltd v MVB Business Exchange Centres Ltd, [2018] UKSC 24

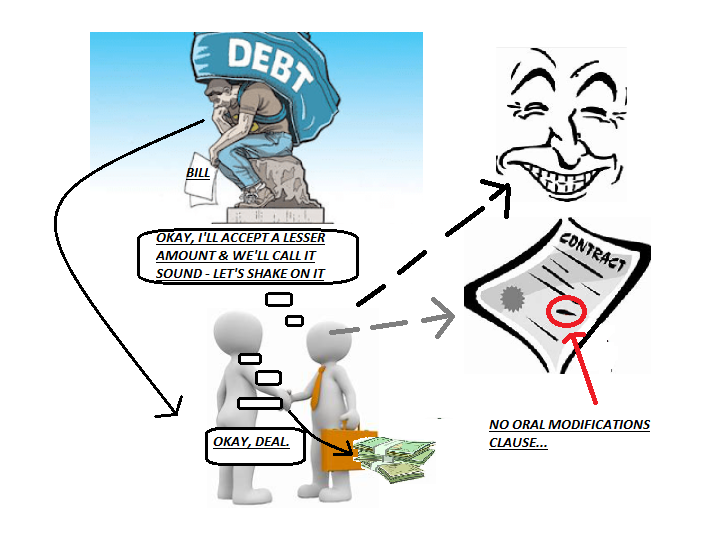

Rule of thumb:How do ‘no oral modifications’ clauses work? Minor-obligations/warranties within a contract can generally be varied by the parties to the contract orally or by custom over the course of time (material obligations/conditions cannot), however, where there is a ‘no oral modification’ clause in the contract, these minor-terms/warranties cannot be varied orally or by custom and to a large extent are set in stone, although if the words used or conduct thereafter are absolutely ‘unequivocal’ then variation in some exceptional circumstances may be able to be applied.

Background facts:

The facts of this case were that Rock Advertising had not paid several months of rent for their office with MVB Business Exchange Centre. MVB’s credit controllers/debt collectors agreed for Rock to pay back £3,500, which was a large chunk of what Rock owed. Rock agreed this because they thought that this payment cleared all their debts and let them go back to ‘business as usual’ with a clean slate. However, MVB locked Rock out of their office and stated that Rock were not getting back in until they paid.

Parties argued:

Rock claimed that MVB had agreed to vary their contract and agree a deal with them, whereas MVB argued that there was a ‘no oral variation’ clause in the contract which meant that the full amount of the debt as stated in one of the first terms of the contract still applied.

Judgment:

The Court partially upheld Rock’s argument but found in favour of MVB. They affirmed that a term of this nature was a peripheral-esque term which could in theory be changed by word of mouth or custom, however, the Court held that where there is a ‘no oral variation’ clause, no written term of a contract can be changed unless it is actually expressly agreed in writing. MVB were within their rights to lock Rock out of their rented premises until they paid the full amount in accordance with the specific term of the contract they were relying on.

Ratio-decidendi:

‘15. If, as I conclude, there is no conceptual inconsistency between a general rule allowing contracts to be made informally and a specific rule that effect will be given to a contract requiring writing for a variation, then what of the theory that parties who agree an oral variation in spite of a No Oral Modification clause must have intended to dispense with the clause? This does not seem to me to follow. What the parties to such a clause have agreed is not that oral variations are forbidden, but that they will be invalid. The mere fact of agreeing to an oral variation is not therefore a contravention of the clause. It is simply the situation to which the clause applies. It is not difficult to record a variation in writing, except perhaps in cases where the variation is so complex that no sensible businessman would do anything else. The natural inference from the parties’ failure to observe the formal requirements of a No Oral Modification clause is not that they intended to dispense with it but that they overlooked it. If, on the other hand, they had it in mind, then they were courting invalidity with their eyes open. 16. The enforcement of No Oral Modification clauses carries with it the risk that a party may act on the contract as varied, for example by performing it, and then find itself unable to enforce it. It will be recalled that both the Vienna Convention and the UNIDROIT model code qualify the principle that effect is given to No Oral Modification clauses, by stating that a party may be precluded by his conduct from relying on such a provision to the extent that the other party has relied (or reasonably relied) on that conduct. In some legal systems this result would follow from the concepts of contractual good faith or abuse of rights. In England, the safeguard against injustice lies in the various doctrines of estoppel. This is not the place to explore the circumstances in which a person can be estopped from relying on a contractual provision laying down conditions for the formal validity of a variation. The courts below rightly held that the minimal steps taken by Rock Advertising were not enough to support any estoppel defences. I would merely point out that the scope of estoppel cannot be so broad as to destroy the whole advantage of certainty for which the parties stipulated when they agreed upon terms including the No Oral Modification clause. At the very least, (i) there would have to be some words or conduct unequivocally representing that the variation was valid notwithstanding its informality; and (ii) something more would be required for this purpose than the informal promise itself: see Actionstrength Ltd v International Glass Engineering In Gl En SpA [2003] 2 AC 541, paras 9 (Lord Bingham), 51 (Lord Walker). 17. I conclude that the oral variation which Judge Moloney found to have been agreed in the present case was invalid for the reason that he gave, namely want of the writing and signatures prescribed by clause 7.6 of the licence agreement’, Lord Sumption.

‘What the parties to such a clause have agreed is not that oral variations are forbidden, but that they will be invalid…. At the very least, (i) there would have to be some words or conduct unequivocally representing that the variation was valid notwithstanding its informality; and (ii) something more would be required for this purpose than the informal promise itself’, Lord Sumption

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.