Ebrahimi v Westbourne Galleries Ltd [1973] AC 360

Citation:Ebrahimi v Westbourne Galleries Ltd [1973] AC 360

Link to full Judgment on Swarb.

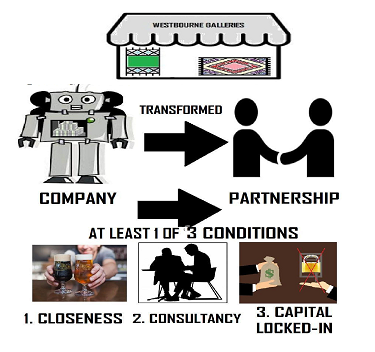

Rule of thumb:Even though a company is registered, can it still be argued that the company is in reality a partnership and partnership law applies to it instead of company law? Yes, you can. The Court in this case affirmed the principle of ‘quasi partnership’ – it was affirmed that where a company is set up, but it is being run like a partnership in practice, with essentially close dealing between shareholders and directors, then partnership law rather than company law applies to the running of the organisation rather than company. This case a very important one and serves as a stark reminder to shareholders in companies not to meddle in the day-to-day operations of companies they invest in, with concerns being formally raised at Annual General Meetings in the standard manner.

Background facts:

The facts of this case were that Ebrahimi and Nazar were partners for a prolonged period. They worked in the rugs business – buying rugs from manufacturers and wholesalers and selling them on at a profit. They decided to form a company to run the business, called Westbourne Galleries Ltd, and transferred all their assets to the company, rather than use the partnership model. When running the Westbourne Galleries company they both paid themselves the profits as a director’s salary, rather than use the dividend function, meaning that the shares in the company were effectively worthless. Nazar convinced Ebrahimi to allow Nazar’s son to have shares in the Westbourne Galleries company and become a director. Nazar and Ebrahimi grew apart. Nazar and his son used their shareholdings to vote out Ebrahimi as a director – as dividends were basically never paid this meant that Ibrahimi no longer made any money from the company. This meant that Nazar had shares in Westbourne Galleries without any value and he could no longer access any of the assets of the company to go into business for himself. Nazar sought to wind the Westbourne Galleries company up and have all its assets divided amongst them so that he could get a hold of his capital and go into business for himself. Nazar refused to release this capital in Westbourne Galleries to Ebrahimi. Ebrahimi took the matter to Court to try to get a ‘winding up order’ for the Westbourne Galleries company so that he could get a hold of some of the assets.

Argument:

Ebrahimi argued that the purpose of the company was over as circumstances were now significantly different from the point when he invested in the company. Nazar argued that nothing had really changed in the ‘rugs’ market or in the Westbourne business and that the significantly different purpose principle of company Ebrahimi was relying on for his ‘winding up order’ did not apply. Nazar further argued that the law does not protect people against folly when someone enters a disadvantageous agreement, and it was Ebrahimi’s own fault that he entered a contract that he did not read properly and think through carefully enough, meaning the winding up order of Ebrahimi should be refused.

Judgment:

The Court arrived at a landmark Judgement in favour of Ebrahimi. The Court held that even although this was a company, in practice it was being run as a ‘quasi-partnership’ – even though there was a company there, Ebrahimi and Nazar were essentially business partners. This meant that Ebrahimi was able to rely on the principle of partnership law that allows a partner the right to dissolve the partnership at any time and take their assets out of the partnership. The Court ordered the ‘Westbourne’ ‘quasi-partnership’ between Ebrahimi and Nazar to be wound up so that Ebrahimi could take his proportionate share of the assets. The Court set a tripartite criteria for when a company will be held to actually be a ‘quasi-partnership’... One or more of (i) a close relationship between 2 of the people; (ii) shareholders being consulted on how to run the day-to-day business operations; and (iii) shares that cannot be easily transferred to a third party.

Ratio-decidendi:

‘My Lords, in my opinion these authorities represent a sound and rational development of the law which should be endorsed. The foundation of it all lies in the words 'just and equitable' and, if there is any respect in which some of the cases may be open to criticism, it is that the courts may sometimes have been too timorous in giving them full force. The words are a recognition of the fact that a limited company is more than a mere legal entity, with a personality in law of its own: that there is room in company law for recognition of the fact that behind it, or amongst it, there are individuals, with rights, expectations and obligations inter se which are not necessarily submerged in the company structure. That structure is defined by the Companies Act and by the articles of association by which shareholders agree to be bound. In most companies and in most contexts, this definition is sufficient and exhaustive, equally so whether the company is large or small. The 'just and equitable' provision does not, as the respondents suggest, entitle one party to disregard the obligation he assumes by entering a company, nor the court to dispense him from it. It does, as equity always does, enable the court to subject the exercise of legal rights to equitable considerations; considerations, that is, of a personal character arising between one individual and another, which may make it unjust, or inequitable, to insist on legal rights, or to exercise them in a particular way. It would be impossible, and wholly undesirable, to define the circumstances in which these considerations may arise. Certainly the fact that a company is a small one, or a private company, is not enough. There are very many of these where the association is a purely commercial one, of which it can safely be said that the basis of association is adequately and exhaustively laid down in the articles. Lord Wilberforce ‘1/4 The superimposition of equitable (partnership) considerations requires something more, which typically may include one, or probably more, of the following elements: 2/4 (i) an association formed or continued on the basis of a personal relationship, involving mutual confidence - this element will often be found where a pre-existing partnership has been converted into a limited company; 3/4 (ii) an agreement, or understanding, that all, or some (for there may be 'sleeping' members), of the shareholders shall participate in the conduct of the business; 4/4 (iii) restriction upon the transfer of the members' interest in the company - so that if confidence is lost, or one member is removed from management, he cannot take out his stake and go elsewhere’. Lord Wilberforce

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.