Ashington Piggeries Ltd v Christopher Hill Ltd, HOL (1972; AC 441)

Citation:Ashington Piggeries Ltd v Christopher Hill Ltd, HOL (1972; AC 441)

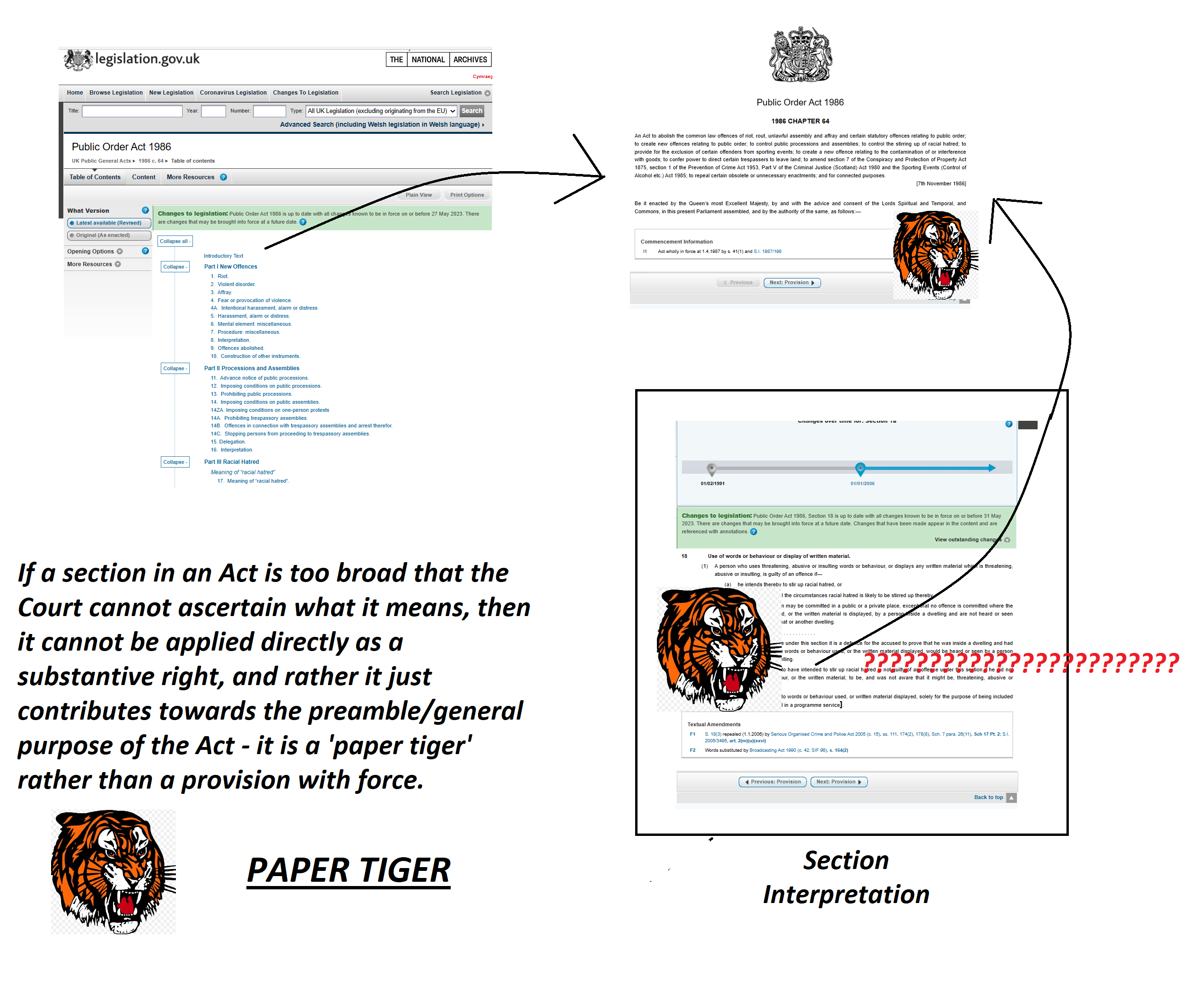

Rule of thumb:If statutory provisions are too broad such that they become meaningless, can a Court apply them? No. This is a seminal point in relation to public policy & statutory interpretation. The seminal rule in this case is that if statutory provisions are too broadly worded a person cannot be held by a Court to be in breach of them - the Court takes a restrictive approach to the interpretation of statutes in regards to this. In other words, statutory provisions that are broadly worded are almost as good as useless for using them to plead a case in Court - broadly worded statutory provisions could be called 'paper tigers' because they look impressive on paper but are of no use in practice. In order for a person to be deemed to have a contract provision in breach of statute or regulation, these statutes or regulations have to be clearly breached, and if there is any ambiguity in the statutory or regulatory provision the contract term will not be held to be in breach of it. Vague and generalised statutory provisions are basically meaningless as primary sources of law.

Background facts:

The facts of this case were that Ashington Piggeries were making 'pig-feed' to feed their pigs. They used an ingredient in doing this that they obtained from Christopher Hill. When Ashington mixed this ingredient with another one to make the pig-feed it would be toxic for some animals. This led to some of Ashington's pigs dying due to eating this food.

Arguments:

Ashington sought damages under the Sale of Goods Act from Hill arguing that the ingredient provided was sub-standard and in breach of statutes relating to the quality of goods. Ashington further argued that they should have been given advice from Hill about the potential of this happening according to a provisions. Hill argued that the ingredient itself was not toxic and if used in a different manner to make pig feed then it would have been perfectly fine. Hill argued that Ashington knew just as much as them about the consequences of mixing certain ingredients and feeding them to some animals, meaning that this provison of the Act did not apply.

Judgment:

The Court upheld the arguments of Hill. They affirmed that this statutory provision relating to quality could not be extended to make this good from Hill be deemed to be in breach of it as although it was of low quality it was not actually defective or non-functional, and could indeed be used in some contexts as part of a balanced diet. They further held that Hill was not in breach of the provision for him to provide advice about the product, as Ashington knew just as much as Hill about it. The Court affirmed that a fairly restrictive approach to deeming a statutory provision to be in breach of an Act, and in order for this to occur a contractal term has to be clearly in breach of the Act.

Ratio-decidendi:

‘Unless the Sale of Goods Act 1893 is to be allowed to fossilise the law and to restrict the freedom of choice of parties to contracts for the sale of goods to make agreements which take account of advances in technology and changes in the way in which business is carried on today, the provisions set out in the various sections and subsections of the code ought not to be construed so narrowly as to force upon parties to contracts for the sale of goods promises and consequences different from what they must reasonably have intended. They should be treated rather as illustrations of the application to simple types of contract of general principles for ascertaining the common intention of the parties as to their mutual promises and their consequences, which ought to be applied by analogy in cases arising out of contracts which do not appear to have been within the immediate contemplation of the draftsman of the Act in 1893,’ (Lord Diplock), ‘...consideration with the preceding common law shows that what the Act had in mind was something quite simple and rational: to limit the implied conditions of fitness or quality to persons in the way of business, as distinct from private persons.’, Lord Diplock, ‘I would have no difficulty in holding that a seller deals in goods ‘of that description’ if he accepts orders to supply them in the way of business and this whether or not he has previously accepted orders for goods of that description... Equally I think it is clear (as both courts have found) that there was reliance on the respondents’ skill and judgment. Although the Act [ie section 14(1) of the Sale of Goods Act 1893] makes no reference to partial reliance, it was settled, well before the Cammell Laird case [1934] AC 402 was decided in this House, that there may be cases where the buyer relies on his own skill or judgment for some purposes and on that of the seller for others. This House gave that principle emphatic endorsement...’, Lord Wilberforce.

'unless the Sales of Goods Act 1893 is to be allowed to fossilise the law and to restrict the freedom of choice of parties to contracts for the sale of goods to make agreements... (although) ought not to be construed so narrowly', Lord Diplock, 'the buyer relies on his own skill and judgement ... This House gave that principle emphatic endorsement', Lord Wilberforce

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.