Silkin v. Beaverbrook Newspapers Ltd., [1958] 1 W.L.R. 743

Citation:Silkin v. Beaverbrook Newspapers Ltd., [1958] 1 W.L.R. 743

Link to case on Canada University.

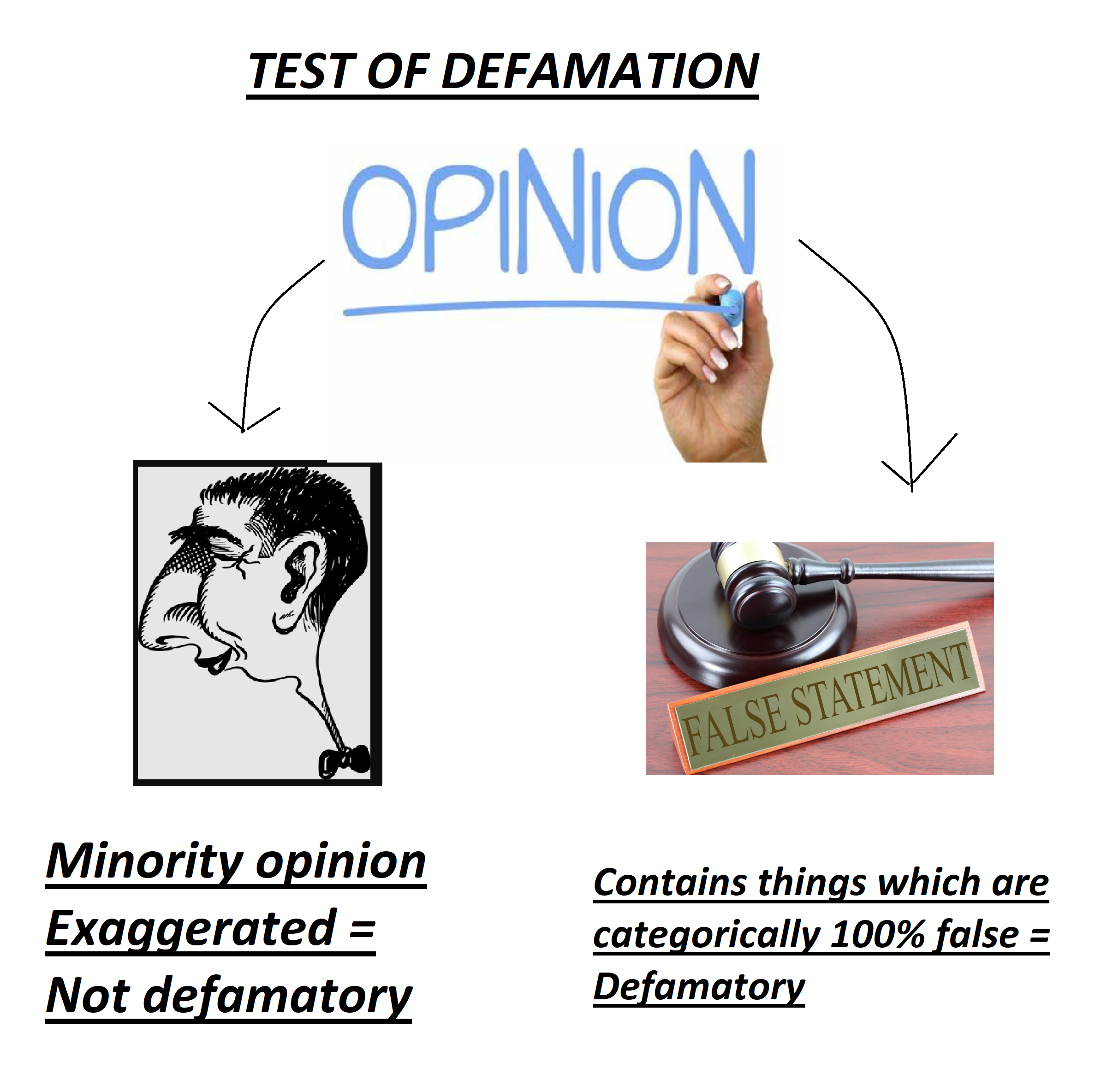

Rule of thumb:Are you allowed to hold exaggerated or extreme opinions in society? Yes, you are – the test of defamation is very high – it is has to be completely & categorically false such that no one in their right mind can believe it in order to be defamatory.

Judgment:

This is a seminal case on the law of defamation and often referred as a fundamental starting block in arguments The Court in this case affirmed that people are allowed to hold exaggerated and strong opinions about people as long as they are honestly felt, and if there nothing technically categorically wrong with what they have said, then they have not breached any laws saying or writing what they did. There is a constitutional right to freedom of speech, and where something is true, then it is able to be said, even if it damages someone’s reputation, and even if it is exaggerated or prejudiced. The test is not whether speech is rational and balanced and fair comment, rather the test is that there is nothing technically completely false that has been said. However, if something has been said which is categorically false, and is damaging, then this is a breach of the law. If this false view has been said dishonestly then this is a particularly flagrant breach of the law.

Ratio-decidendi:

‘Let us look a little more closely at the way in which the law balances the rights of the public man, on the one hand, and the rights of the public, on the other, in matters of freedom of speech. In the first place, every man, whether he is in public life or not, is entitled not to have lies told about him and by that is meant one is not entitled to make statements of fact about a person which are untrue and which redound to his discredit, that is to say, tend to lower him in the estimation of right-thinking men. What are the limits of the right of comment? Quite rightly they are very wide. First of all, who is entitled to comment? The answer to that is ‘everyone.’ A newspaper reporter or a newspaper editor has exactly the same rights, neither more nor less, than every other citizen, and the test is no different whether the comment appears in a Sunday newspaper with an enormous circulation, or in a letter from a private person to a friend or, subject to some technical difficulties with which you need not be concerned, is said to an acquaintance in a train or in a public house. So in deciding whether this was fair comment or not, you dismiss from your minds the fact that it was published in a newspaper, and you will not, I am sure, be influenced in any way by any prejudice you may have for or against newspapers any more than you will be influenced in any way by any prejudice which you may have for or against Lord Silkin’s politics . . referring to fair comment, because that is the technical name which is given to this defence, or, as I would prefer to say, which is given to the right of every citizen to comment on matters of public interest. But the expression ‘fair comment’ is a little misleading. It may give you the impression that you, the jury, have to decide whether you agree with the comment, whether you think it is fair. If that were the question you had to decide, you realise that the limits of freedom which the law allows would be greatly curtailed. People are entitled to hold and to express freely on matters of public interest strong views, views which some of you, or indeed all of you, may think are exaggerated, obstinate or prejudiced, provided – and this is the important thing – that they are views which they honestly hold. The basis of our public life is that the crank, the enthusiast, may say what he honestly thinks just as much as the reasonable man or woman who sits on a jury, and it would be a sad day for freedom of speech in this country if a jury were to apply the test of whether it agrees with the comment instead of applying the true test: was this an opinion, however exaggerated, obstinate or prejudiced, which was honestly held by the writer?’, Lord Diplock

People are entitled to hold and to express freely on matters of public interest strong views, views which some of you, or indeed all of you, may think are exaggerated, obstinate or prejudiced, provided – and this is the important thing – that they are views which they honestly hold.

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.