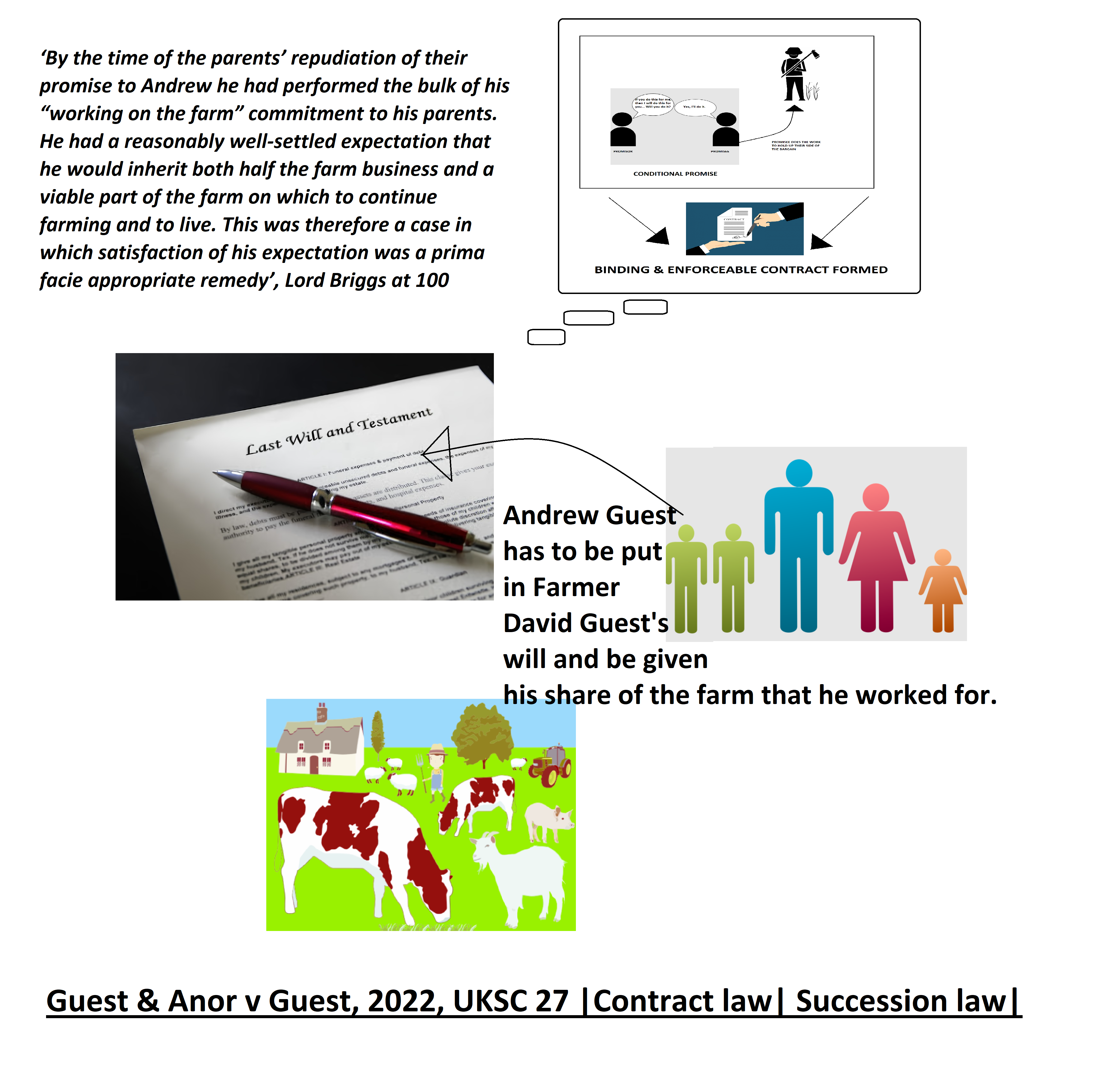

Guest & Anor v Guest, 2022, UKSC 27

Citation:Guest & Anor v Guest, 2022, UKSC 27.

Subjects invoked: 15. 'Contract'.3. 'Succession'.

Rule of thumb:Can parents write their children out their will? If a person promises they will include you in their will if you do something for them, can they refuse to put you in their will? If your parents orally promise you (word of mouth not in writing) that they will give you a part of their house in their will on the condition that you do work on the house for them, and you do this work, if you later fall out with your parents, can they go back on their promise and cut you out of their will? No, generally speaking if someone says they’ll include you in their will if you do something for them, then this is binding. And, no, your parents cannot write you out their will in those circumstances. Even although promises normally have to be put in writing to be binding, and a person is entitled to change their mind over their will any time before they die, if a conditional oral promise is made by a promisor to a promisee, and the promisee acts upon the condition of this promise to their financial loss, then this promise becomes a legally contract binding which cannot be reneged upon despite not being put in writing. This succession/wills contract between parents and children in this scenario is set in stone and cannot be changed.

Background facts:

This case invoked the subjects of succession law and contract law. Many arguments based on different principles from these subjects were made, but the Court held that it was the contract law principle of ‘conditional promise to financial detriment’, also referred to more technically accurately as ‘proprietary estoppel’, or ‘personal bar’ in Scotland, which applied in this case.

The facts and basic laws of this case could not be put more eloquently and succinctly than those written by Lord Briggs at the beginning of his Judgment in paragraph 1-2. Here is this quote redacted, ‘“One day my son, all this will be yours”. Spoken by a farmer to his son when in his teens, and repeated for many years thereafter. Relying on that promise of inheritance from his father, the son spends the best part of his working life on the farm, working at very low wages, accommodated in a farm cottage, in the expectation that he will succeed his father as owner of the farm, to be able to continue farming there… Many years later, father and son fall out… they can no longer work together or even live in close proximity. The son has no alternative but to leave… Meanwhile the father cuts him out of his will…'

The answer to this question legally was that the law of contract applied between Farmer David Guest and his son Andrew Guest to ensure Andrew Guest could not be cut out of the will. From the subject of contract law the general principle of ‘promise’ applied, and the particular sub-principle of ‘conditional oral promise acted upon to the financial detriment of the promisee’ applied in this case. A promise normally has to be put in writing in order to become a legally binding contract, however, an exception to this exists where if a conditional promise is made orally by the promisor, and the other party, the promisee, spends money fulfilling the condition of the promise set out by the promisor, then the promise becomes a legally binding contract that the promiser cannot not get out of.

Judgment:

The Court held that the principle of succession law stating that a person could change their will any time before they died, and the broad principle that promises are only binding if they are made in writing, were both trumped in this case by the promise sub-principle exception of ‘conditional promise acted upon the financial detriment of the promisee applied’, a principle also referred to as ‘proprietary estoppel’ or ‘personal bar’. In short, Farmer David Guest was not legally allowed to cut his son Andrew Guest out of the will because Farmer Guest had made a conditional promise to his son Andrew Guest, which Andrew Guest subsequently acted upon to his financial detriment to perfect this condition, thereby making the conditional oral promise become a legally binding contract. Farmer David Guest would have to pass his farm on to his 2 sons, Andrew Guest and Ross Guest, as well as his daughter Jan Guest – Andew Guest was not allowed to be cut out of the will. In terms of the practicalities of this, the Court held that Farmer David Guest either had to pass on the ownership of his farm to his 3 children via a conveyance with Farmer David Guest & his wife made the trustees of this farm for the rest of their life, or, have the farm valued by a surveyor and pay one third of the price of this paid to Andrew Guest there and then, with the Court leaving these options to be decided between the parties.

This is a good case for demonstrating the importance of the ‘conditional promise’ principle under contract law, also often called ‘personal bar’ or ‘estoppel’, which can apply widely across society and not just in succession law. If one party, a promisor, orally promises another party, a promisee, that they the promisor will do something on the condition that the promisee does something else for them first, if the promisee holds up their part of the bargain, then a legally binding contract is formed thereafter and the promisor must carry out what they said they would do. This ‘conditional promise’/ proprietary estoppel/ personal-bar in this context can also be called a legally binding quid pro quo as well. This an important principle to be aware of to be used against people in society who do not stick to their word.

Ratio-decidendi:

‘By the time of the parents’ repudiation of their promise to Andrew he had performed the bulk of his “working on the farm” commitment to his parents. He had a reasonably well-settled expectation that he would inherit both half the farm business and a viable part of the farm on which to continue farming and to live. This was therefore a case in which satisfaction of his expectation was a prima facie appropriate remedy’, Lord Briggs at 100

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.