Carruthers v. Carruthers' Trustees [1896] UKHL 809 (13 July 1896)

Citation:Carruthers v. Carruthers' Trustees [1896] UKHL 809 (13 July 1896)

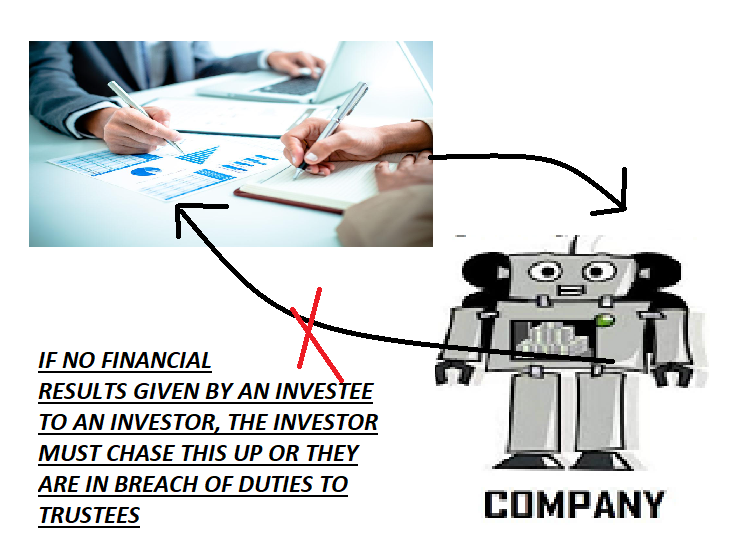

Rule of thumb:If investors do not get financial results from the people they have invested in, are they legally bound to check this up? Yes. This is a seminal case in investment law. If a trustee invests money in an organisation and the organisation does not provide financial results, the trustee has to chase this up timeously and take action or else they can be made responsible for the loss.

Background facts:

The basic facts of this case were that a large sum of money at that time, £62, was given to investors to act as a trustee over. This was then redistributed by the trustees to a specialist factor to invest in residential property. The factor initially provided annual accounts showing how the money had been invested and what it stood at – it increased to £104. However, one year accounts showing the balance of the money were not provided by the factor to the trustees. The trustees however did not see this as a red flag and chase this up. When the trustees finally did chase this up the factor had absconded with the money. If the factor had been chased up earlier then the likelihood was that he would have been caught.

Judgment:

The Court affirmed that this was a breach of a trustee’s duties at common law. A trustee has to provide annual statements on the status of the money invested with them. They also have a basic duty to act diligently and follow a correct process before investing the money to try to grow it at a reasonable rate. If a trustee invests this in a factor/business they have to have checks in place for keeping scrutiny over this and if accounts are not provided chase these up timeously, or else the trustee can be liable for the money invested. The Court affirmed that Carruthers was owed by the trustees the money invested plus a reasonable rate of return for the period they were trustees over it, and the last known point of the funds. In short, the trustees had to pay Carruthers £104 for beaching trustees’ duties at common law.

Ratio-decidendi:

‘They have from the outset of the trust many years ago administered it through one of their own number appointed as their factor, and remunerated for his services in that capacity out of the trust funds. At common law the trustees had no power to take that course. Under the trust they had power to do so, but subject to this very plainly expressed condition, that there should be an annual and regular audit of the factor's accounts. With that audit the trustees practically dispensed. That is said to have been a mere matter of omission, and in one view that may be taken of it, it was a mere matter of omission, but the result, and the necessary result, was that the course of their administration as actually conducted was sanctioned neither by the common law of trusts nor by the provision of the deceased's deed. I certainly am not prepared to hold that an active course of administration which cannot be defended or justified either on the ground of its being consistent with the common law, or on the ground of its being consistent with the provisions of the trust-deed, can be regarded as a mere “omission.” But it is unnecessary in this case to go any further than the character of the act, even on the assumption that it ought to be treated as a matter of omission. The immunity clause of the Act of 1861, or a similar immunity conferred by the terms of a trust-deed, does not afford a protection to trustees against any act or omission which according to the law is regarded as constituting culpa lata. My Lords, I think the acting of the trustees in this case did amount to culpa lata. I should be very sorry to hold that the systematic disregard of a check enacted by the testator in his trust-deed—a reasonable check—and in some cases, as the experience of the present action has shown, a necessary precaution, does not constitute culpa lata’, Lord Watson at 812, ‘My Lords, during the year 1890 sums of money were received by Mr Hall Grigor, which, after allowing for the balance of £61 odd that had been due to him, left in his hands a sum of £104, 2s… If the conclusion is a probable one that the accounts delivered in 1891 would have been in order, and all would have appeared to have been properly paid, then there would be nothing to excite the suspicions of the trustees, and they would have been acting with perfect propriety if during the rest of the year 1891 they had left the matter as theretofore in the hands of Mr Hall Grigor, in which case he would have received the moneys, the time for audit would not have arrived, and he would have misappropriated them before the trustees had any opportunity of ascertaining that anything was wrong. Under those circumstances I do not see my way to hold the respondents liable for more than this sum of £104, 2s. 7d., which was in the hands of the factor prior to the termination of the year 1890. I think therefore that the proper course in the present case will be to reverse the interlocutors appealed from, and to declare that the respondents are bound to make good to the trust-estate the sum of £104, 2s. 7d. with interest from the 31st of January 1891’, Lord Herchell at 811.

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.