Salomon v A Salomon & Co Ltd [1896] UKHL 1

Citation:Salomon v A Salomon & Co Ltd [1896] UKHL 1.

Rule of thumb basic:Is a company deemed to be an actual person as a matter of law? Yes, as a matter of law, a company is deemed to be a person.

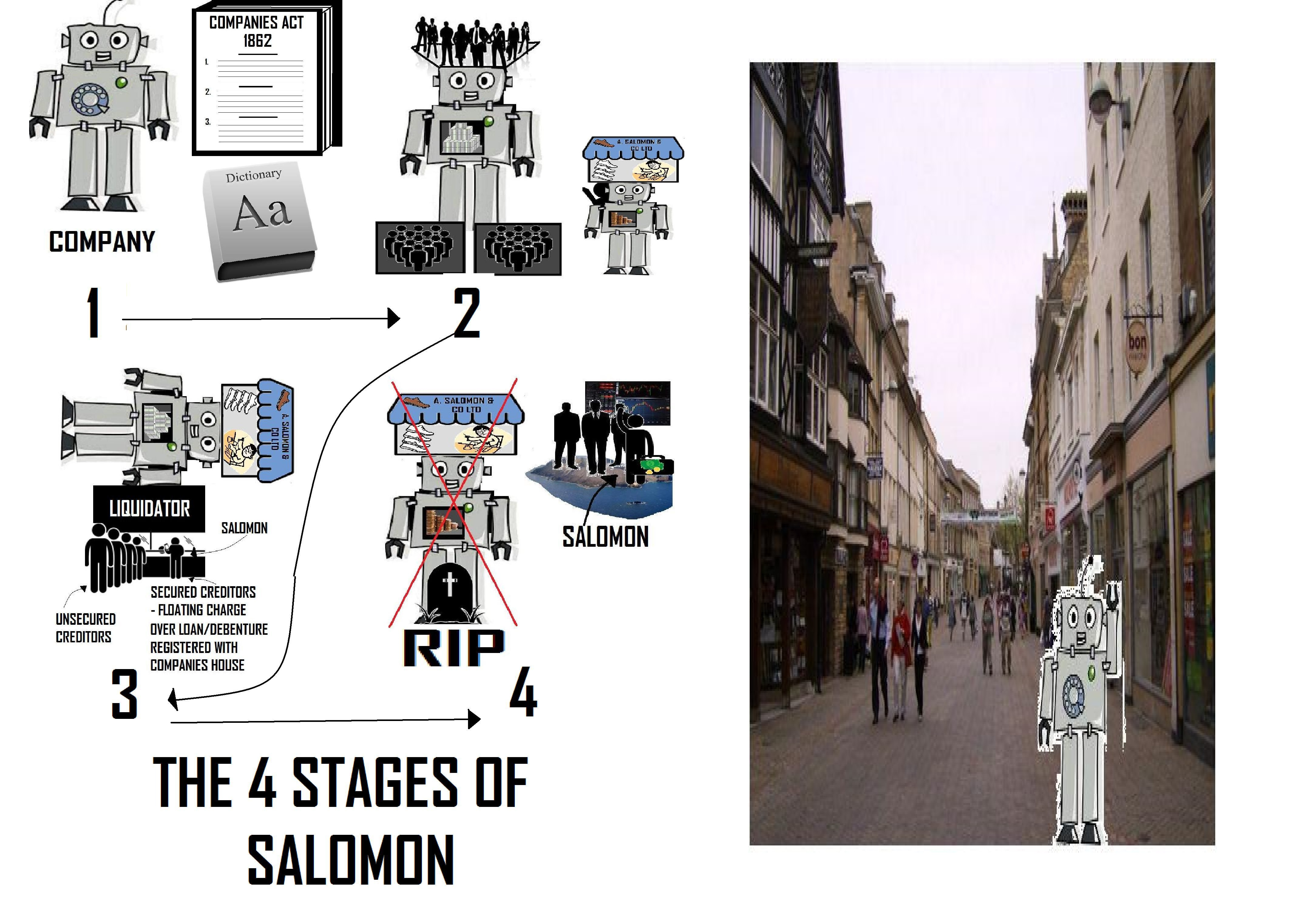

Rule of thumb advanced:This is one of the most famous cases in UK law as 4 famous, long-standing legal principles were established in it – (i) the application of the ‘golden approach’ to the interpretation of legislation was adopted. Namely, if a statute is interpreted literally and provides a clear answer on what the law is, then no other primary or secondary sources of law are of any relevance in determining the law in the matter. The preamble and intent of the Companies Act 1862 was literally interpreted. A literal interpretation of the provisions of The Companies Act 1862 using the ordinary grammatical meaning of the words in the statute was then taken. As the statute was clear the debates in Parliament about the 1862 Act during its passage through Parliament were of no relevance. (ii) It affirmed that ‘one-man companies’ are perfectly valid companies. Where someone is a director and owns all the shares, even for many micro and small businesses, they are still perfectly valid companies. This case affirmed that businesses of all sizes, including small ones like A. Salomon Ltd, were able to use the company structure. A company did not have to have a certain amount of capital or number of employees or directors before it could utilise the company structure for its business – it could be used by all businesses of all sizes. (iii) ‘Separate personality’ of companies was affirmed. This case effectively stated that when a company is created it is like the creation of a new legal person – almost like a robot person or a Frankenstein type person. The investors are therefore not liable for any of the debts run up by the company. (iv) It affirmed that debenture holders, whose loans to the company are correctly registered with Companies House, get their money back first if the company goes insolvent. They have a ‘floating charge’ which crystallises upon insolvency, and they are ‘preferred creditors’ in the insolvency process meaning that they their money back first ahead of other creditors in the event of a winding up of the business. They are able to collect their debts before other creditors even if they were the last people to give credit to the company.

Background facts:

The facts of this case were that Mr Salomon was a shoe-maker who had operated for a long time in his own name personally and built up a good reputation. Salomon had often been given credit by people and had always paid his debts. Salomon then became the owner/founder/director of A Salomon and Co Ltd, using the company structure rather than the sole trader structure as his business model, and properly informed people of this change in business structure. Salomon invested a lot of his own capital in the business, and he registered this as a ‘debenture loan’ with Companies House. The business was doing well for a while but ran into financial difficulties and went into insolvency. Mr Salomon believed he should be able to get a large chunk of his debenture loan back out of the company as a preferred creditor, and that he was ahead of the other debtors in the queue. The liquidator of A. Salomon Ltd did not believe that Salomon was entitled to any money from the company, and also sought even more money from Salomon personal bank account in addition to the money in the company bank account.

Parties argued:

The liquidator of A. Salomon Ltd made various arguments as to why Salomon was not entitled to the money he took for his debenture loan and why he was liable himself personally for the debts of the company. The liquidator argued that: (i) a purposive approach should be taken to the Companies Act, (ii) one man companies were invalid, (iii) debentures holders were not valid preferential creditors, and (iv) that an exception against separate for personality for shareholder directors should be created.

Judgment:

The Court took a literal interpretation of the Companies Act and all 4 arguments of the liquidator were rejected by the Court – namely it dismissed extracts from Parliamentary debates as being irrelevant because the statute was clear. The Court further held that Salomon one man companies were valid, the company was a separate person meaning shareholders were not liable for debts, and that people whose loans were registered with Companies House were to be paid back first. This case demonstrated how taking a literal approach of a statute rather than a purposive one can lead to a totally different outcome in the case.

Ratio-decidendi:

(Quote 1) ‘I am wholly unable to follow the proposition that this was contrary to the true intent and meaning of the Companies Act. I can only find the true intent and meaning of the Act from the Act itself; and the Act appears to me to give a company a legal existence with, as I have said, rights and liabilities of its own, whatever may have been the ideas or schemes of those who brought it into existence’, Lord Halsbury. (Quote 2)‘The fact that Mr. Salomon raised 5000l. for the company on debentures that belonged to him seems to me strong evidence of his good faith and of his confidence in the company. The unsecured creditors of A. Salomon and Company, Limited, may be entitled to sympathy, but they have only themselves to blame for their misfortunes. They trusted the company, I suppose, because they had long dealt with Mr. Salomon, and he had always paid his way; but they had full notice that they were no longer dealing with an individual, and they must be taken to have been cognisant of the memorandum and of the articles of association. For such a catastrophe as has occurred in this case some would blame the law that allows the creation of a floating charge. But a floating charge is too convenient a form of security to be lightly abolished. I have long thought, and I believe some of your Lordships also think, that the ordinary trade creditors of a trading company ought to have a preferential claim on the assets in liquidation in respect of debts incurred within a certain limited time before the winding-up. But that is not the law at present. Everybody knows that when there is a winding-up debenture-holders generally step in and sweep off everything; and a great scandal it is’, Lord MacNaghten, (quote 3) ‘It has become the fashion to call companies of this class "one man companies." That is taking a nickname, but it does not help one much in the way of argument. If it is intended to convey the meaning that a company which is under the absolute control of one person is not a company legally incorporated, although the requirements of the Act of 1862 may have been complied with, it is inaccurate and misleading: if it merely means that there is a predominant partner possessing an overwhelming influence and entitled practically to the whole of the profits, there is nothing in that that I can see contrary to the true intention of the Act of 1862, or against public policy, or detrimental to the interests of creditors. If the shares are fully paid up, it cannot matter whether they are in the hands of one or many. If the shares are not fully paid, it is as easy to gauge the solvency of an individual as to estimate the financial ability of a crowd’, Lord MacNaghten, (Quote 4) ‘Either the limited company was a legal entity or it was not. If it was, the business belonged to it and not to Mr. Salomon… If it was not, there was no person and no thing to be an agent at all; and it is impossible to say at the same time that there is a company and there is not’, Lord Halsbury

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.