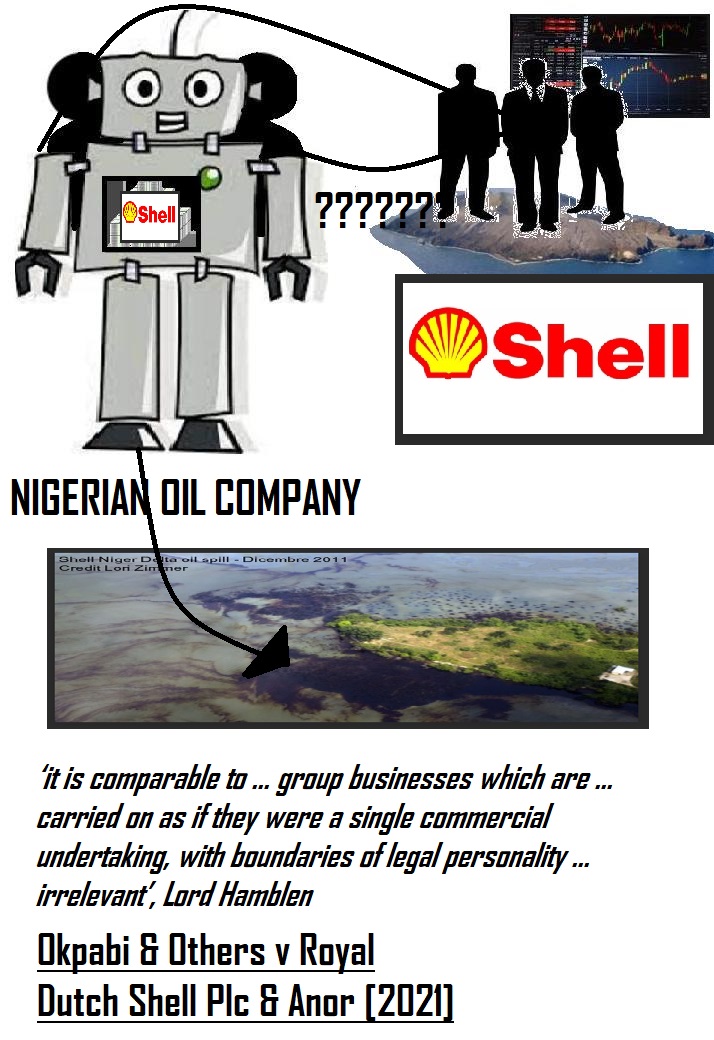

Okpabi & Others v Royal Dutch Shell Plc & Anor [2021] UKSC 3 (12 February 2021)

Citation:Okpabi & Others v Royal Dutch Shell Plc & Anor [2021] UKSC 3 (12 February 2021)

Subjects invoked: 7. 'Company'.12. 'Procedure'.24. 'Environmental nuisance'.

Rule of thumb: questions:1, Is there one perfect jurisdiction to hear a legal claim or can Courts in multiple countries be used? 2, what is the standard for a care being deemed to be relevant so that it can proceed to trial? 3, when can a person who is influencing another person be liable for acts in breach of the law that person does – when does influence change to control to bring vicarious liability?

Rule of thumb: answers:This case affirmed 3 important points of law – the first 2 points were in the subject of procedure law, and the 3rd was in the subject of partnership law. Firstly, it affirmed the procedural principle of ‘jurisdiction shopping’. A national Court only has to possess a ‘sufficient link’ to the parties or the incident in question – more than one country can have a ‘link’ to the case, with the Courts in multiple countries often able to hear and decide a case. In other words, a case does not have to be raised in the country with the best link, just a sufficient link, and people can ‘shop’ so to speak to see which country they would prefer to have their case heard in. Secondly, it affirmed that under the procedural principle of ‘relevancy’, not that high a level of potential success is required in order to meet the test of ‘relevancy’ – only some evidence suggestive of a possibility of a breach of law has to be shown – the case does not have to be strong, just merely arguable with some sort of outside mathematical possibility of success due to a moderately persuasive legal argument. In other words, under the test of relevancy, a horse on a racecourse with odds to win of 50-1 or so to win is still ‘relevant’ according to the legal test of ‘relevancy’. Thirdly, in the field of partnership law, it established that if a holding company is providing one of its subsidiaries with a lot of ‘advice’ and ‘guidance’ in relation to day-to-day activities, then this may be deemed to be ‘influence’ verging into 'control', and both companies will thereafter be deemed to be ‘partners’ with 'vicarious liability' & joint and several liability arising, rather than separate personalities. The Court held that evidence has to be scrutinised to establish if a holding company has overstepped their remit as an investor seeking general summarised financial information about the subsidiary, into actually ‘influencing’ their subsidiary’s operations.

Background facts:

The facts of this case were that Royal Shell were/are an oil exploration and extraction company. They wholly owned a subsidiary company that was doing oil exploration and extraction work in Nigeria. However, Shell’s subsidiary company put the oil-pipes and sealants down in Nigeria in an unsatisfactory manner. This led to the oil bursting out of the pipes and oil going everywhere in this coastal-part of Nigeria. Around 50,000 people in Nigeria suffered financial loss and damage as a result of this oil spillage, but the subsidiary had nowhere near enough money in it or assets to provide all of these 50,000 Nigerian people with compensation for the damage they suffered. The 50,000 Nigerians therefore formed a loose kind of association, and this association raised a case against the holding company, Royal Shell, to pay them for the losses that they suffered as a result of the spillage. The Nigerian association of claimants sued Royal Shell in the High Court in England and Wales for this. These claimants provided documents showing various interactions between people in the subsidiary company and people at the holding company Royal Shell. The claimants were also seeking more information disclosures from Royal Shell and the subsidiary to further build their case. The High Court at first instance ‘struck’ out this case of the Nigerian claimants on preliminary procedural grounds. The High Court held that not enough evidence was presented by the Nigerian Association of claimants to show a sufficient strength of influence and link between Royal Shell and its subsidiary, meaning that the company law principle of separate personality applied to exclude holding company from blame. The High Court struck this case out without a full trial on the matter being held. The Nigerian association of claimants appealed to the UK Supreme Court.

Royal Shell made various arguments to support their case. They argued firstly that England and Wales was the wrong jurisdiction to hear the case in. They showed why other jurisdictions, such as Holland where a lot of their paper files were kept and their witnesses in the matter resided, the country of their headquarters, were far better suited to hearing the case. They secondly argued that there was not enough evidence to show a strong enough link between them and their subsidiary - evidence to show clear influence being exerted on day-to-day operations in the subsidiary. Shell argued that as there was no correspondence actually showing influence on how day-to-day operations were being carried, rather just typical business and investor-investee correspondence being provided, the case should be deemed to be incompetent/irrelevant and dismissed on procedural grounds. Shell argued that any information requests made to them in a trial would be fishing exercises, which was not allowed procedurally.

The Nigerian claimants made several arguments to support their position. Firstly, the Nigerian claimants argued that there was a sufficiently strong link for the case to be heard in England and Wales, where Shell had a strong base of operations – they also argued that based upon principles such as independence, impartiality, high level jurisprudence and counsel etc, this was where they believed they had the best chance of getting a fair and credible trial in the matter - a Judgement which believe could actually believe projected truth and justice. Secondly, they argued that the standard of relevancy was far lower than Royal Shell were making out. They argued that in the documentation they provided, there were some communications which could be interpreted go beyond the seeking of just financial information, and were actually correspondence regarding how operations were being carried out. They argued that the test of relevancy was being misapplied and said to be much higher than it actually was – they argued that to pass the relevancy test only a remote percentage chance of winning had to be shown, not a high chance. Thirdly, the Nigerian claimants argued that within the documentation they provided there were interactions between Shell and the subsidiary which could be construed as being about how to lay pipes – they argued that this meant Royal Shell overstepped the boundary of being a distant investor at ‘arms-length’ from their subsidiary and they became partners with their subsidiary. The Nigerian claimants argued that this was enough evidence to make a basic case that should run to trial, especially as if there was a full run to trial under Court ‘disclosure’ they could gain access to more correspondence to build their case even further.

Judgment:

The Court upheld the arguments of the Nigerian claimants. They held firstly that in the full circumstances of the case there was a sufficient link with the UK for the UK Courts to be able to hear the case. The Court affirmed that the test was sufficient link, and not best placed Court, so many Courts could potentially validly hear a case. Secondly, they affirmed that the case was ‘relevant’. It was established that the test for relevancy is a low one – in order to establish a relevant case it does not have to have a good chance of success, it just has to have some sort of chance of success – even odds of 1 Judge in 50 or 1 Judge in 100 thinking that the case has been made are sufficient to satisfy the relevancy principle – relevancy only applies where the case has no mathematical chance of success and no Judge in their right mind could support it. Thirdly, the Court affirmed that there was a possibility that Royal Shell overstepped their mark of being a distant investor with separate personality and became an operational partner. The Court affirmed that this would have to be looked at in detail – it was not clear and questions did have to be asked about some of the evidence. The UK Supreme Court referred the case back to the High Court so that a full trial could be carried out to see if there were sufficient guidance about day-to-day operations by Shell to their subsidiary in order to establish joint and several liability for Shell’ subsidiary under partnership law in the matter.

The UK Supreme Court also formulated the general principles that are to be taken cumulatively in deciding whether an investor/holding company has overstepped their mark and become their investee’s ‘partner’: (i) someone who has a management role in the holding company also having a management role in the subsidiary, (ii) evidence of actual advice about how to do operational things provided to the subsidiary, (iii) general documents about how to do things provided to both holding company and subsidiary, and (iv) holding company stating it influences the subsidiary – ‘we’ll get them to do this’, or, ‘we get them to do that’.

Ratio-decidendi:

‘14. … It was therefore unnecessary for the judge to make any findings on the disputed issues of appropriate forum and/or access to justice in Nigeria…. 153. I have set out a detailed summary of the appellants’ case at paras 24-69 above. Having full regard to the respondents’ written and oral submissions and evidence, I do not consider that it has been shown that the averments of fact made in the particulars of claim should be rejected as being demonstrably untrue or unsupportable. On that basis, it is my view that the case set out in the pleadings … establish that there is a real issue to be tried… 157. (1/2) Whilst “formal binding decisions” are taken at corporate level, these are taken on the basis of prior advice and consent from the vertical Business or Functional line and organisational authority generally precedes corporate approval. Whilst the respondents suggested that RDS could only delegate responsibility for its own corporate governance and group-wide strategy functions, the RDS Control Framework shows that the CEO and the RDS ExCo have a wide range of responsibilities, including for “the safe condition and environmentally responsible operation of Shell’s facilities and assets”. 157 (2/2) It is the appellants’ case that the Shell group’s vertical organisational structure means that it is comparable to Lord Briggs’ example of group businesses which “are, in management terms, carried on as if they were a single commercial undertaking, with boundaries of legal personality and ownership within the group becoming irrelevant” (para 51). 158. How this organisational structure worked in practice and the extent to which the delegated authority of RDS, the CEO and the RDS ExCo was involved and exercised in relation to decisions made by SPDC are very much in dispute, as is apparent from the witness statements. It is also an issue in relation to which proper disclosure is of obvious importance. It clearly raises triable issues…’, Lord Hamblen ‘it is comparable to … group businesses which are … carried on as if they were a single commercial undertaking, with boundaries of legal personality … irrelevant’, Lord Hamblen

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.