Ivey v Genting Casinos (UK) Ltd (t/a Crockfords) [2017] UKSC 67 (25 October 2017)

Citation:Ivey v Genting Casinos (UK) Ltd (t/a Crockfords) [2017] UKSC 67 (25 October 2017)

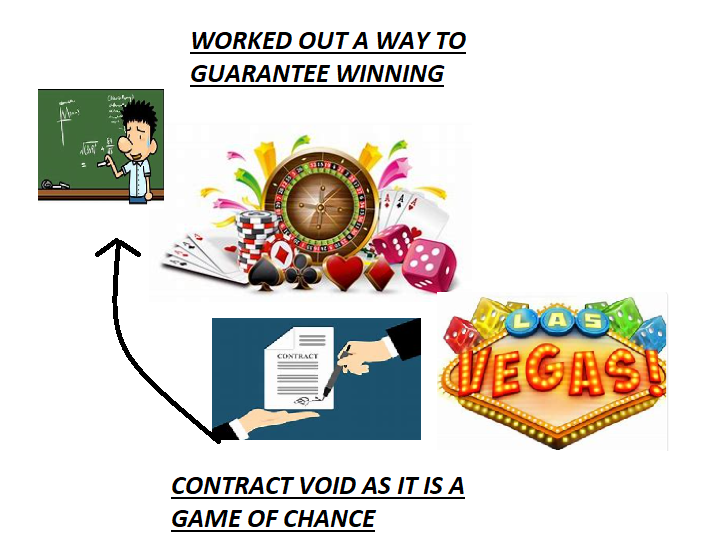

Rule of thumb:Where a person has worked out a strategy to guarantee beating the bookies in a casino game or otherwise, does the bookie have to award the winnings for these? No, where this is being done the contract is void and the bookie does not have to pay this out.

Background facts:

The facts were that a punter had worked out to guarantee ‘beating the bookie’.

Parties argued:

The bookmaker did not pay out arguing they have a clause against ‘dishonesty’ in their contract. The pursuer argued that this was not ‘dishonest’ as he was not breaking any criminal fraud laws, and he did not believe that people would consider what he was doing dishonest – it was still very difficult to perform his strategy and required a lot of practice to perfect (and a lot of people still do not win using them) which he stated that he firmly believe most people would not consider dishonest (especially as well given how much bookmakers make off of gamblers) - which is normally the test for ‘dishonesty’.

Judgment:

The Court held that ‘dishonesty’ had to be interpreted more broadly in this contractual matter. In this case ‘edge-sorting’, leading to Mr Ivey winning around £7 million, was held to be ‘dishonest’ strategy as per the terms of the contract between bookmakers and gamblers, meaning that bookmakers did not have to pay out over because this arrangement. This Judgement has been criticised in some quarters and could potentially be challenged again in the future.

Ratio-decidendi:

‘... A significant refinement to the test for dishonesty was introduced by R v Ghosh [1982] QB 1053. Since then, in criminal cases, the judge has been required to direct the jury, if the point arises, to apply a two-stage test. Firstly, it must ask whether in its judgment the conduct complained of was dishonest by the lay objective standards of ordinary reasonable and honest people. If the answer is no, that disposes of the case in favour of the defendant. But if the answer is yes, it must ask, secondly, whether the defendant must have realised that ordinary honest people would so regard his behaviour, and he is to be convicted only if the answer to that second question is yes... These several considerations provide convincing grounds for holding that the second leg of the test propounded in Ghosh does not correctly represent the law and that directions based upon it ought no longer to be given. The test of dishonesty is as set out by Lord Nicholls in Royal Brunei Airlines Sdn Bhd v Tan and by Lord Hoffmann in Barlow Clowes: see para 62 above. When dishonesty is in question the fact-finding tribunal must first ascertain (subjectively) the actual state of the individual’s knowledge or belief as to the facts. The reasonableness or otherwise of his belief is a matter of evidence (often in practice determinative) going to whether he held the belief, but it is not an additional requirement that his belief must be reasonable; the question is whether it is genuinely held. When once his actual state of mind as to knowledge or belief as to facts is established, the question whether his conduct was honest or dishonest is to be determined by the fact-finder by applying the (objective) standards of ordinary decent people. There is no requirement that the defendant must appreciate that what he has done is, by those standards, dishonest. Therefore in the present case, if, contrary to the conclusions arrived at above, there were in cheating at gambling an additional legal element of dishonesty, it would be satisfied by the application of the test as set out above. The judge did not get to the question of dishonesty and did not need to do so. But it is a fallacy to suggest that his finding that Mr Ivey was truthful when he said that he did not regard what he did as cheating amounted to a finding that his behaviour was honest. It was not. It was a finding that he was, in that respect, truthful. Truthfulness is indeed one characteristic of honesty, and untruthfulness is often a powerful indicator of dishonesty, but a dishonest person may sometimes be truthful about his dishonest opinions, as indeed was the defendant in Gilks. For the same reasons which show that Mr Ivey’s conduct was, contrary to his own opinion, cheating, the better view would be, if the question arose, that his conduct was, contrary to his own opinion, also dishonest’, Lord Hughes

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.