Lee v. Alexander [1883] UKHL 877 (3 August 1883)

Citation:Lee v. Alexander [1883] UKHL 877 (3 August 1883)

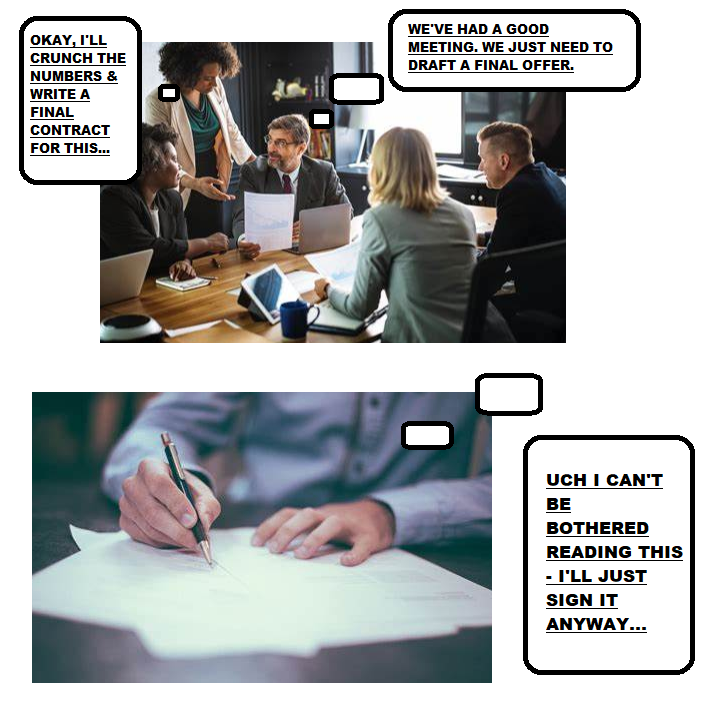

Rule of thumb:What happens if you are negotiating a contract at a meeting, are happy with what is agreed orally at the meeting, have a contract sent in writing which you then sign without reading, and only later discover that the written terms were different from the terms you negotiated orally? Do the oral terms or the written terms apply? This is a classic mistake which the law provides no redress for when people do not bother to read the written terms. The written terms apply and not the oral ones. The final contract supersedes all previous drafts & oral agreements.

Background facts:The basic facts of this case were that the 2 parties had been negotiating a contract for the purchase of land. When the actual contract came along the written contract was very different from the negotiations although not hugely different.

Parties argued:One party argued that if a contract was completely different to all the other negotiations then there was an obligation to inform the other party of this who was entitled to assume otherwise that the contract would largely follow all the other negotiations. The other party argued that nothing false was said and it was expected that a person would read a contract before signing it.

Court held:The Court held that where there has been a signed written agreement, this is largely deemed to supersede all of the other documentation and representations. The person who agreed the contract which clearly stated what was being purchased & said nothing else false was allowed to keep the land contracted for.

Ratio-decidendi:

‘I do not think there is any ambiguity in the language of the disposition of December 1879 which can justify a reference, for the purpose of controlling that language, to an antecedent agreement between the appellant and the respondent. Nor do I think that such a reference is warranted either by the fact that the subjects conveyed are described in general terms in the dispositive clause of the deed, or by the fact that in the narrative of the deed the parties are represented as having agreed upon certain points which were presumably matter of stipulation in any written agreement which preceded its execution. In the present case the deed narrates that the appellant and respondent had previously arranged certain terms and conditions, but it makes no mention of any document in which these are to be found. Even if the narrative had borne that these terms and conditions had, inter alia, been agreed to by missive letters of the 13th October 1879, that would not in my opinion have made these letters admissible evidence for the purpose of controlling or qualifying the language of the deed. According to the law of Scotland, the execution of a formal conveyance, even when it expressly bears to be in implement of a previous contract, supersedes that contract in toto, and the conveyance thenceforth becomes the sole measure of the rights and liabilities of the contracting parties. To admit the letters of October 1879, for the purpose and for the reasons explained in the opinions of the Lord President and Lord Mure, would, in my humble opinion, be inconsistent with the principles which ought to govern the construction of a probative deed of conveyance’, Lord Watson at 880

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.