Uber BV v Aslam & Others [2021] UKSC 5 (19 February 2021)

Citation:Uber BV v Aslam & Others [2021] UKSC 5 (19 February 2021).

Subjects invoked: 41. 'Employment'.

Rule of thumb:What is the test for determining if someone is an independent contractor or an employee? The basic rule is control - if someone moves beyond influening another person & actually controls them then this will be deemed to bring vicarious liability & establish an employee-employer relationship.

Background facts:

This was a case in the subject of employment law – it invoked the principle of vicarious liability.

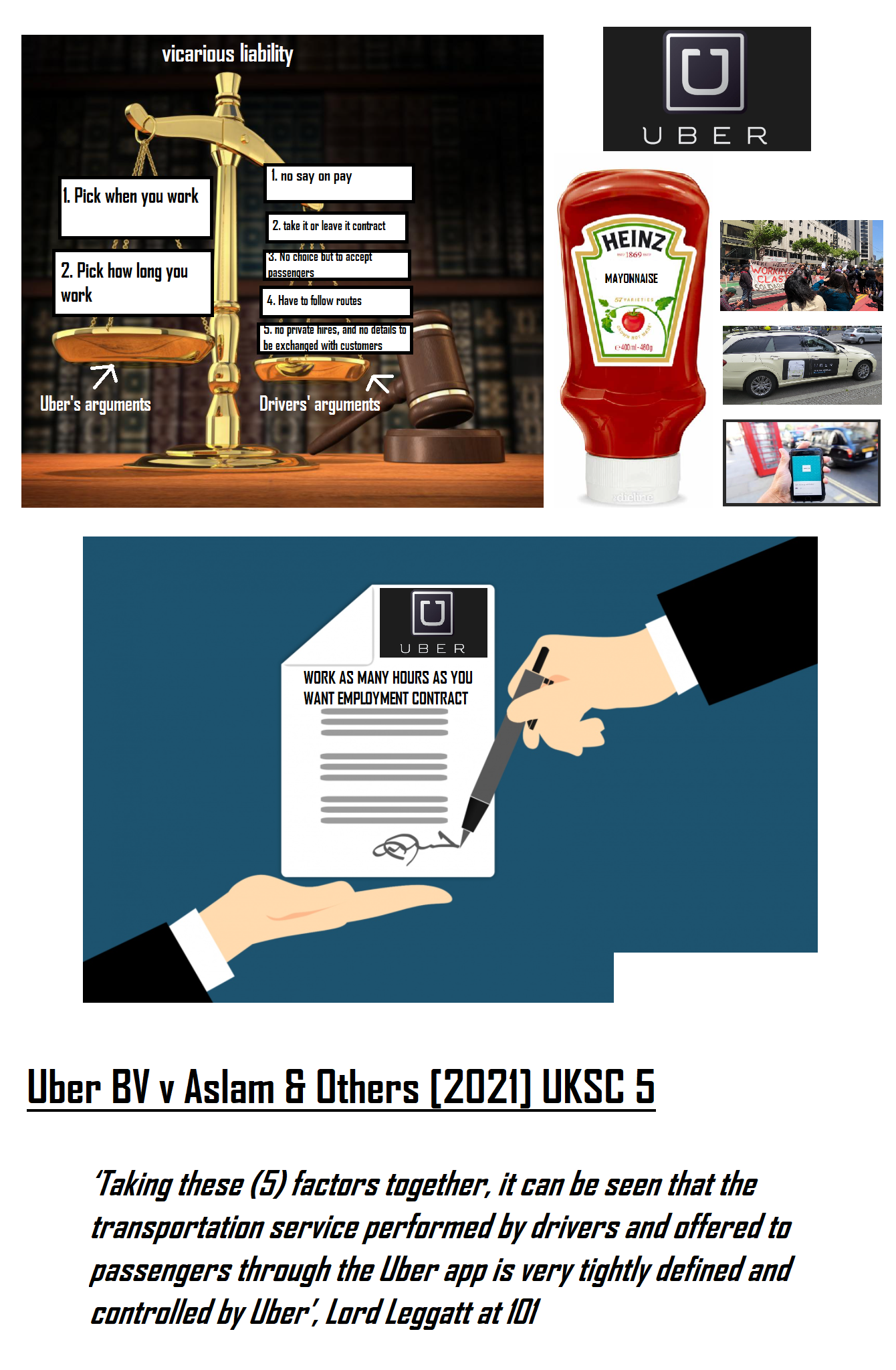

The backgrounds facts of this case were that Uber drivers were disgruntled about their commercial relationship with Uber and their so-called ‘independent contractor’ status. The drivers believed that they were ‘employees’ of Uber rather than ‘independent contractors’ like Uber told them they were, which would entitle the drivers to minimum wage and paid holidays, which would add up to the drivers receiving a lot more money than they had received from Uber. The Court thoroughly considered the facts of the drivers’ relationship with Uber. A number of factors about the relationship were taken into account. Uber highlighted that 3 crucial and fundamental facts were: (i) drivers could pick whenever they wanted to work; (ii) drivers could work however long they wanted; (iii) a 20% commission ‘technology fee’ was taken by Uber for getting in the customers/passengers and delivering the address they needed picked up to the drivers, and everything over and above that was profit for the driver. The drivers identified 5 factors about the operations of the relationship: (i) Uber controlled how much the drivers charged; (ii) the contract terms set by Uber were non-negotiable – there was no negotiations whatsoever or even a formal sitting down and signing of the contract; (iii) once a driver was logged into the system they had very little choice as to whether or not they accepted an Uber-proposed passenger; (iv) Uber effectively set the conditions/routes on ‘sat-nav’s’ for how they had to drive; (v) Uber forbade drivers from exchanging any details with customers to allow drivers to build a client base.

Both parties in this case agreed about the principle invoked – namely that if one party to a contract has such a strong influence over the other party that this other party is basically under tight control, then this other party is not an independent contractor, and instead they are an employee. Both parties also agreed that in order for this principle to apply, it is an accumulation of factors which all add up to determine whether an independent contractor was under such tight control as to actually make them an employee – it was basically for the Court to weigh-up if the factors cumulated sufficiently to constitute an employee relationship or not. It was a straightforward, back-and-forth and diametrically opposed legal argument. The Uber drivers basically argued that with their interpretation of the laws all of the factors added up to put them on a tight leash and make them an employee; Uber argued that their interpretation of relevant laws was that all of the factors did not add up to make them an employee and drivers still had a sufficient degree of freedom to make them independent contractor. It was basically up to the Court to consider all the relevant case-law and legislation and then have the final say.

Judgment:

The Court upheld the arguments of the Uber drivers. The Court held that the accumulation of the 5 keys factors set about by the Uber drivers: (i) Uber setting the fares (the most important factor), (ii) no negotiation at all on terms – ‘take it or leave it’ offers from Uber; (iii) Uber creating a system where drivers had to accept proposals to pick up passengers from Uber; (iv) Uber effectively dictating how drivers drove with ‘sat-nav’; and, (v) Uber not allowing drivers to exchange details with any customers so they could not build their own practice, ensured drivers were de facto ‘employees’. The Court did emphasise that all cases of this nature have to be weighed up individually, with cases turning on certain factors being strongly fulfilled as well as a high overall weight of factors. The Court held that the Uber taxi system altogether meant that Uber had such a strong degree of influence over drivers that they controlled them, and the drivers were therefore ‘employees’ rather than ‘independent contractors’. This added a new concept of employment contract ‘pick and choose your hours employment contracts’ – the 2000’s/2010’s brought the era of ‘zero hours employment contracts’, this case was a new moder-day employment evolution.

Ratio-decidendi:

‘90. The claimant drivers in the present case had in some respects a substantial measure of autonomy and independence. In particular, they were free to choose when, how much and where (within the territory covered by their private hire vehicle licence) to work…. 92. … But the focus must still be on the nature of the relationship between drivers and Uber. The principal relevance of the involvement of third parties (ie passengers) is the need to consider the relative degree of control exercised by Uber and drivers respectively over the service provided to them… 93. … Five aspects … are worth emphasising. 94. First and of major importance, the remuneration paid to drivers for the work they do is fixed by Uber and the drivers have no say in it (other than by choosing when and how much to work). Unlike taxi fares, fares for private hire vehicles in London are not set by the regulator. 95. Second, the contractual terms on which drivers perform their services are dictated by Uber… 96. Third, although drivers have the freedom to choose when and where (within the area covered by their PHV licence) to work, once a driver has logged onto the Uber app, a driver’s choice about whether to accept requests for rides is constrained by Uber… 98. Fourth, Uber exercises a significant degree of control over the way in which drivers deliver their services… 100. A fifth significant factor is that Uber restricts communication between passenger and driver to the minimum necessary to perform the particular trip and takes active steps to prevent drivers from establishing any relationship with a passenger capable of extending beyond an individual ride… 101. Taking these factors together, it can be seen that the transportation service performed by drivers and offered to passengers through the Uber app is very tightly defined and controlled by Uber. Furthermore, it is designed and organised in such a way as to provide a standardised service to passengers in which drivers are perceived as substantially interchangeable and from which Uber, rather than individual drivers, obtains the benefit of customer loyalty and goodwill…’, Lord Leggatt ‘Taking these (5) factors together, it can be seen that the transportation service performed by drivers and offered to passengers through the Uber app is very tightly defined and controlled by Uber’, Lord Leggatt at 101

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.