Rylands v Fletcher [1868] UKHL 1

Citation:Rylands v Fletcher [1868] UKHL 1

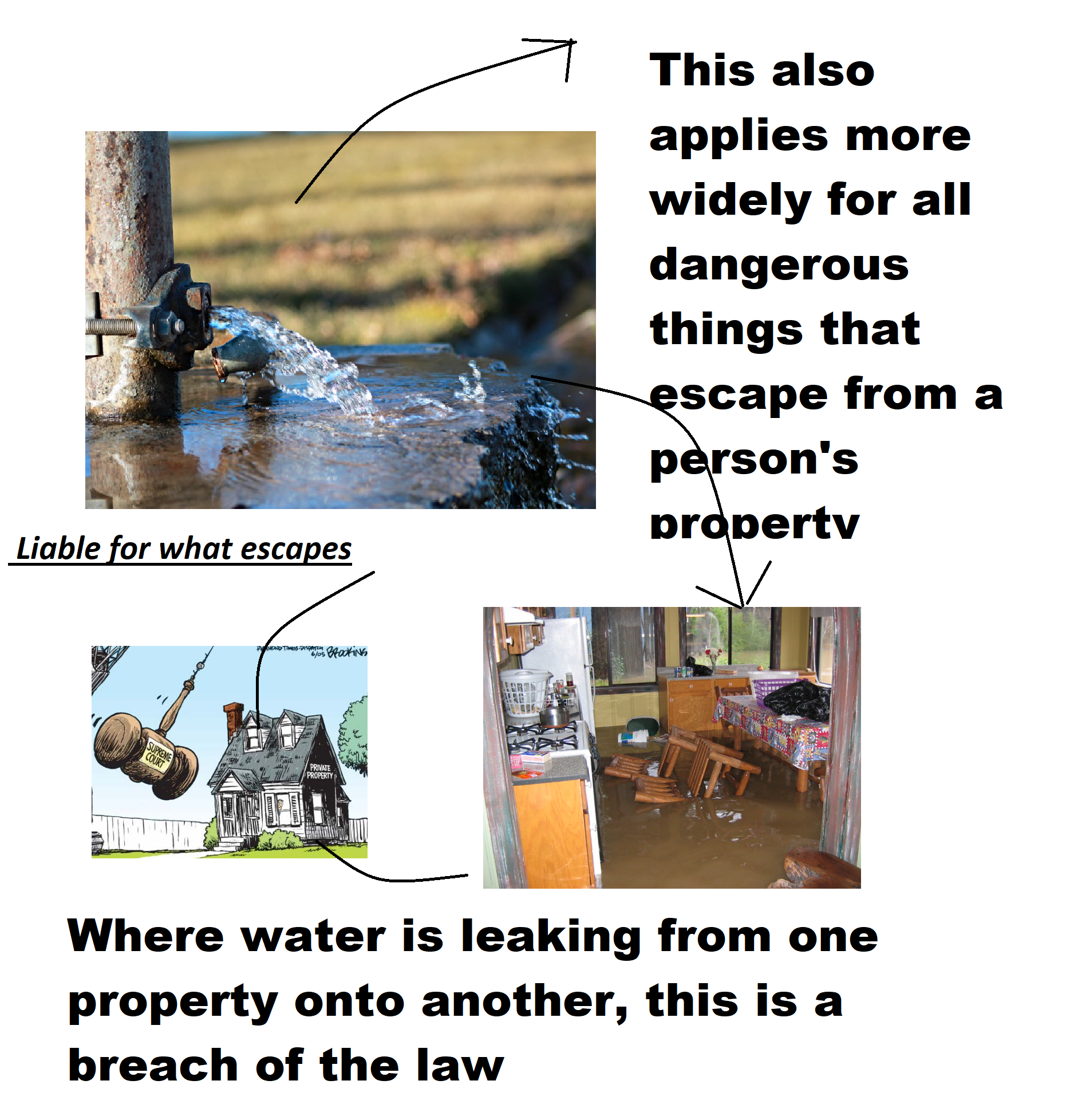

Rule of thumb:where water leaks onto another party’s property then they are liable for the damages caused by this. This also applies more widely for all dangerous things escaping from a person’s property.

Background facts:

The basic facts of this case were that Rylands did building work on his property to create a reservoir. It then started leaking and damaged his neighbour Fletcher’s property.

Parties argued:

Ryland argued that he was not liable but the builder was. Rylands further argued that Fletcher’s use of the land was unnatural and he caused this himself.

Judgment:

The Court affirmed that Ryland was liable for Fletcher’s damages – the Court affirmed that the occupier of the land is first and foremost liable for ensuring that anything dangerous on their property is managed properly by them – whether it be a reservoir or otherwise. The Court did partially uphold the non-natural use arguments made by Rylands, and held that this could be a defence in some circumstances, but as a fact Fletcher’s use of his land was not deemed to be unnatural in this case.

Ratio-decidendi:

‘We think that the true rule of law is, that the person who for his own purposes brings on his land and collects and keeps there anything likely to do mischief, if it escapes, must keep at his peril, and if he does not do so, is prima facie answerable for all the damage which is the natural consequence of its escape… And upon authority this we think is established to be the law, whether the things so brought be beasts, or water, or filth, or stenches’ (Blackburn J). My Lords, the principles on which this case must be determined appear to me to be extremely simple. The Defendants, treating them as the owners or occupiers of the close on which the reservoir was constructed, might lawfully have used that close for any purpose for which it might in the ordinary course of the enjoyment of land be used; and if, in what I may term the natural user of that land, there had been any accumulation of water, either on the surface or underground, and if, by the operation of the laws of nature, that accumulation of water had passed off into the close occupied by the Plaintiff, the Plaintiff could not have complained that that result had taken place. If he had desired to guard himself against it, it would have lain upon him to have done so, by leaving, or by interposing, some barrier between his close and the close of the Defendants in order to have prevented that operation of the laws of nature.... On the other hand if the Defendants, not stopping at the natural use of their close, had desired to use it for any purpose which I may term a non-natural use, for the purpose of introducing into the close that which in its natural condition was not in or upon it, for the purpose of introducing water either above or below ground in quantities and in a manner not the result of any work or operation on or under the land, - and if in consequence of their doing so, or in consequence of any imperfection in the mode of their doing so, the water came to escape and to pass off into the close of the Plaintiff, then it appears to me that that which the Defendants were doing they were doing at their own peril; and, if in the course of their doing it, the evil arose to which I have referred, the evil, namely, of the escape of the water and its passing away to the close of the Plaintiff and injuring the Plaintiff, then for the consequence of that, in my opinion, the Defendants would be liable. As the case of Smith v. Kenrick is an illustration of the first principle to which I have referred, so also the second principle to which I have referred is well illustrated by another case in the same Court, the case of Baird v Williamson,[24] which was also cited in the argument at the Bar’, Lord Cairns

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.