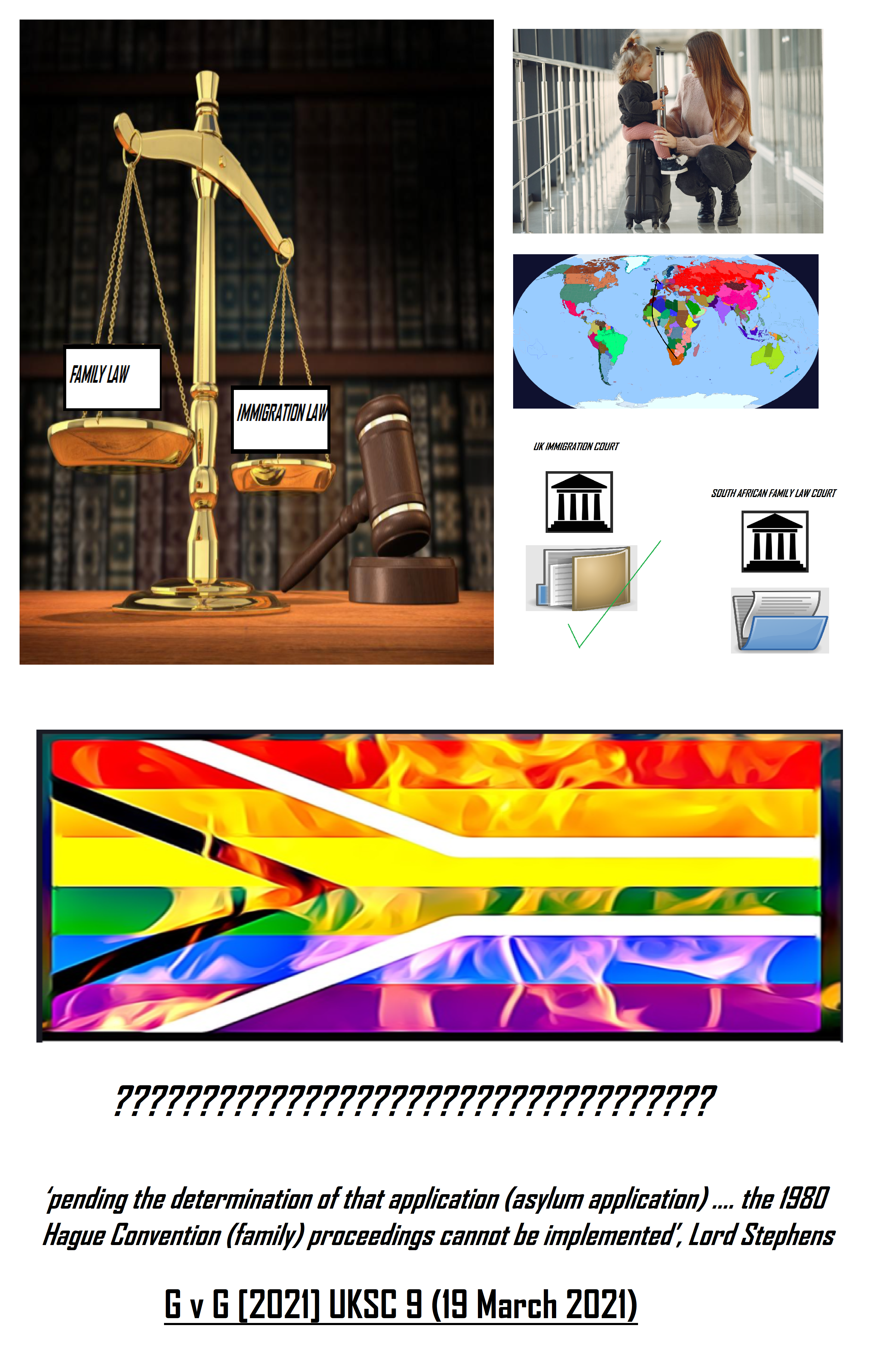

G v G [2021] UKSC 9 (19 March 2021).

Citation:G v G [2021] UKSC 9 (19 March 2021).

Subjects invoked: 12. 'Procedure'.4. 'Family'.76. 'Immigration'.

Rule of thumb:What happens if there are 2 separate legal actions going on at the same time? Which one goes first? Do they both run at the same time? One legal action has to go first and the other legal action has to wait until that one is finished. If there is a family law case & an immigration case at the same time, the family law one has to wait until the immigration action is finalised. The Court firstly stated that 2 actions on a similar topic procedurally could not be allowed to run concurrently, in case of clashes between the findings of the 2 Court. The Court then affirmed that immigration law processes took priority over family law ones, and, that family proceedings could only be commenced against someone once any asylum applications were finished.

Background facts:

This case invoked the subjects of immigration law, family law and procedural law.

The facts of this case were that the 2 parties in the action, Mr G and Mrs G were a married couple living in South Africa with a daughter, who was around 9 years old (their names were made anonymous in the Judgement to protect their child). However, Mrs G came to the realisation that she was bisexual. This caused friction between Mrs G and Mr G, and the relationship came to an end. There was a child custody arrangement in place that Mrs G would generally have their child full-time, and Mr G would have the child every so often at the weekend, and Mr G would have the child for extended periods at school holidays. As time passed Mrs G believed that Mr G, his family and social circle all turned against her. Mrs G believed that she was being persecuted because of her openness about her sexuality. Mrs G was worried that Mr G, his family and social circle would poison her daughter against her, with repeated snide and nasty anti-gay remarks being made about her to her daughter, which she felt were grossly inappropriate because of her daughter’s age.

Mrs G therefore decided to leave South Africa and move to the UK for an initial holiday period. However, Mrs G decided to stay in the UK and made an asylum application, both for her and her daughter, to stay permanently in the UK. Mrs G argued bisexuals were generally persecuted in South Africa, she was at acute risk of this because of her social circumstances, and her young daughter was at risk of psychological damage with regular unsavoury anti-gay remarks being made about her mother from such a young age, and this was the crux of Mrs G’s and her daughter’s asylum applications. Mr G demanded that his daughter be returned to South Africa and the custody agreement be respected. Mrs G refused to let Mr G see his daughter, and so Mr G raised a family law action. The asylum action and the family law action were both in Court at the same time, and there was a dispute over which claim should be heard first.

This case raised an extremely rare point of law. This case did not invoke any standard principle of law. It was agreed that it settled law that 2 cases in a similar topic with potential areas of friction could not be allowed to run in Courts concurrently, with one case having to wait until the end of the other. This case raised the point of law what happened when 2 legal actions in immigration law and family law were pitted against each other, and the Court had to decide which subject took priority over the other to go first.

Mr G sought to raise family proceedings against Mrs G under the International Hague Convention, a family law treaty ratified in both the UK and South Africa, and sought to raise family proceedings to have a custody agreement for his daughter reached and upheld. Mr G emphasised that a key principle of the Hague Convention was for family law matters to be decided swiftly, which gave it priority over immigration law. Mr G argued that a new interim custody agreement should be made expediently. Mr G argued that the family law Court could decide if there was a risk of anti-gay psychological abuse in South Africa. Mrs G argued that no family law cases should take place under hers and her daughter’s asylum applications were finalised. Mrs G insisted that no family law proceedings should take place until the Immigration Court decided whether Mrs G and Mrs G’s daughter were at risk of anti-gay psychological abuse in South Africa. Mrs G also argued that the family law Court could not be allowed to decide this point of law as this was the remit of the immigration Court.

Judgment:

The Court in this case upheld the arguments of Mrs G. The Court affirmed that the family law case must wait until after Mrs G’s asylum application case was finished. The Court affirmed that the question of anti-gay psychological abuse was the remit of the immigration Court, not the family law Court, and that these 2 cases procedurally should not be allowed to run concurrently in case any clashes emerged between the 2 actions.

The Court explained that this was a Judgement they arrived at with great consternation. The Court explained that asylum applications can take years to be finalised, and this would of course not be the best for Mr G or their child, but they had no choice but to allow this to take place. The Court in this called upon the international community to write a new Treaty explaining exactly what to happen in this scenario, with some sort of compromise hopefully being found. The Court in this case also explained that this should be done as a priority, as parents could make ‘sham’ asylum claims to stop the other parent seeing their child, with the Court specifically using the word ‘sham’, and use this as a grossly unfair bargaining tactic in divorce proceedings.

Ratio-decidendi:

‘3. There is a substantial risk that the time taken to determine an asylum application, which even if it is genuine can take months if not years, will frustrate the return of children under the 1980 Hague Convention because, by the time the asylum application concludes, the relationship between a child and the left-behind parent may be harmed beyond repair. In addition, there is a substantial risk of sham or tactical asylum claims being made by the taking parent with the intention of achieving that very objective… 5. The central questions are whether these two Conventions occupy different canvasses and, if not, how they can operate hand in hand in order to achieve the objectives of each of them without frustrating the objectives of either of them’,

'151. …. However, the issue is not whether all asylum appeals have an automatic or suspensive effect. Out-of-country asylum appeals do not have a suspensive effect. Rather, the question is whether a statutory in-country appeal has suspensive effect which in turn depends on whether the suspensive effect is required to provide an effective remedy. Furthermore, applicants are entitled to exercise their statutory right of appeal so that it is not appropriate to require the Secretary of State or an applicant to make an application for an interim order pending the outcome of their appeal.'

'152. I am of the view, for the reasons given by Mr Payne (see paras 145 and 146 above) that there cannot be an effective remedy under an in-country appeal process if in the meantime a child has in fact been returned under the 1980 Hague Convention to the country from which they have sought refuge. Accordingly, an in-country appeal acts as a bar to the implementation of a return order in 1980 Hague Convention proceedings. Due to the time taken by the in-country appeal process this bar is likely to have a devastating impact on 1980 Hague Convention proceedings. I would suggest that this impact should urgently be addressed by consideration being given as to a legislative solution.' Lord Stephens

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.