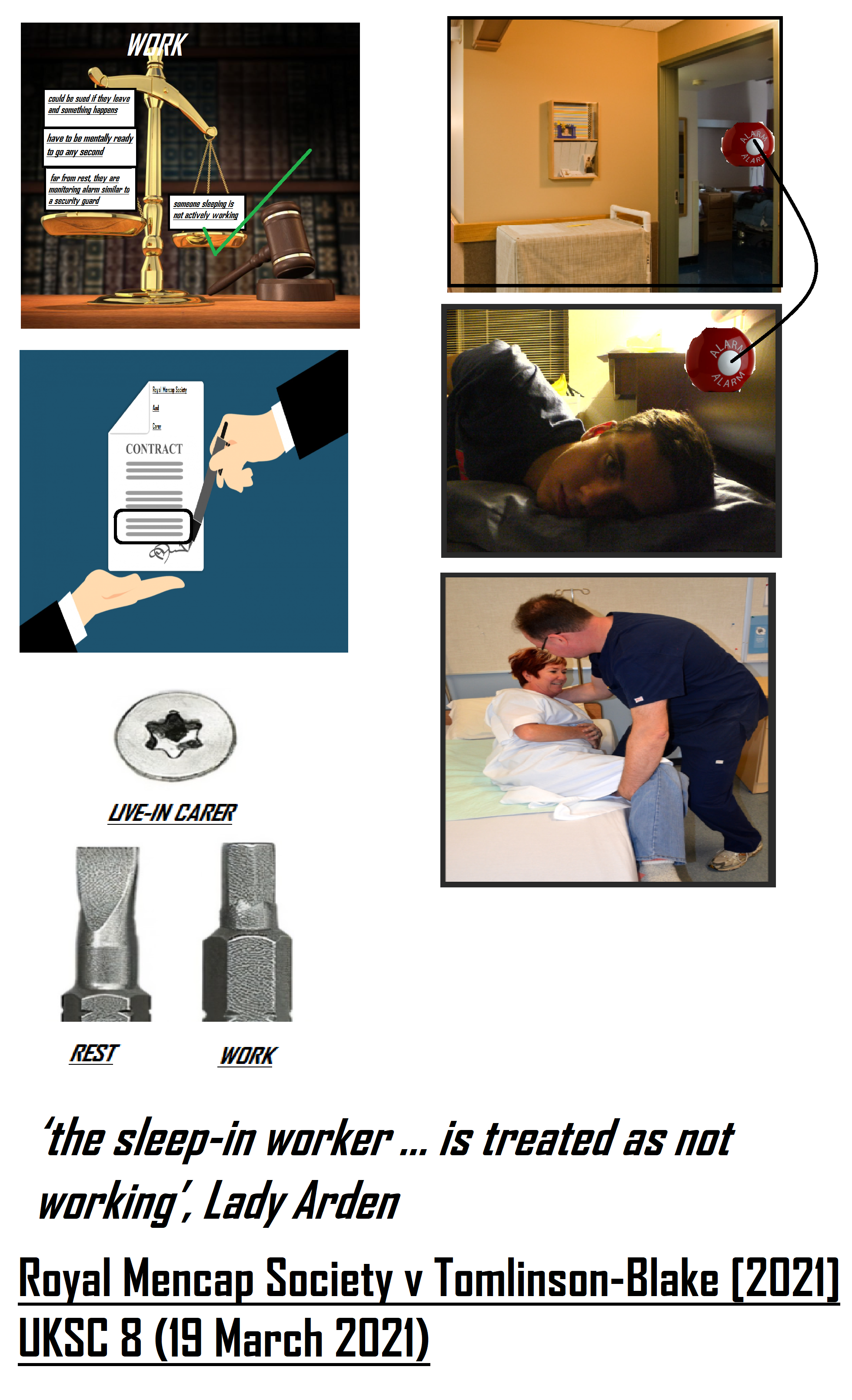

Royal Mencap Society v Tomlinson-Blake [2021] UKSC 8 (19 March 2021)

Citation:Royal Mencap Society v Tomlinson-Blake [2021] UKSC 8 (19 March 2021).

Subjects invoked: 41. 'Employment'.38. 'Discrimination'.

Rule of thumb:Is a carer who is on-call and sleeping deemed to be 'working' as such and thereby entitled to minimum wage? No, the Court held that this did not fall within the defintion of 'work' as such, so there was no entitlement to minimum wage under the auspices of employment law, and people were only entitled to the remneration they agreed contractually.

Background facts:

This case was on the subject of employment law and contract law.

The facts of this case were that Royal Mencap Society (RMS) was an organisation that provided care-services, and Tomlinson Blake was someone they employed to be a live-in carer. When RMS employed Tomlinson Blake they agreed a deal with him where he would be a live in carer for a night with their client, during which time he was free to sleep, but he would have an alarm which the client could trigger, at which point he would have to go and attend to the client. RMS agreed that they would pay Tomlinson Blake a fix-feed for being there ‘on-call’, and if he had to attend to any issues, he would be paid at the minimum wage rate for this. Tomlinson Blake initially accepted this offer, however, after had been doing this for some time he decided that the live-in part of being a carer was much harder than it sounded in theory, as it was extremely difficult to sleep at all and nigh-on impossible to get good quality sleep, and he was not happy with this. Tomlinson Blake told RMS that he wanted paid the minimum wage for the full amount of time that he was on call as a live-in carer. RMS refused to pay Tomlinson Blake this and the matter went to Court.

This was a fairly straightforward legal debate. Both parties agreed that the legal principles invoked in the debate were the principles of ‘work’ and ‘rest’. The matter under dispute was just how far the principles of ‘work’ and ‘rest’ extended. Did the principle of ‘work’ extend so far as to include people sitting around ‘on-call’ potentially waiting to deal with something? Or was being on-call rest?

Tomlinson Blake argued that the time he spent on-call in the houses of people who needed care constituted ‘work’. Whilst he said he was technically able to sleep and rest, he argued that this was not ‘rest’, like you would have whilst on a lunch or tea break in a normal job, but rather was unpleasant as you were always on edge waiting for the alarm to go off, and he argued that this was within the definition of ‘work’ and not the definition of ‘rest’. RMS argued that sitting/lying around resting/sleeping/dozing did not fall within the principle of ‘work’, and instead fell within the principle of ‘rest’. RMS argued that ‘work’ only started when the alarm went off and people then actually had something to do, not before. RMS argued that this matter therefore fell to the common law of contract of people just having to negotiate a price for being on-call, with this not being caught under the definition of work. RMS also argued that even if people are on their tea-break or lunch-break in other workplaces, if the workplace gets extremely busy, or there is emergency, then they can still be called back from work early, so technically therefore every single lunch or tea break across for every employee the whole of the UK could be work which should be remunerated, meaning that to uphold these arguments could very much open the floodgates of claims, which would mean the Court would be stepping out-with their constitutional remit. RMS argued that the principle of ‘rest’ applied to being on-call in this scenario. RMS argued that it was clearly stated that live-in carers were allowed to sleep whilst waiting for the alarm to go off, and they argued that a period when someone is allowed to sleep had to fall within the definition of ‘rest’ rather than ‘work’. RMS argued that it would absurd to call someone sleeping ‘working’.

Judgment:

The Court upheld the arguments of RMS - that sitting around on-call, albeit not a pleasant experience, did not actually constitute ‘work’ as such, and instead was ‘rest’. The Court’s reasoning started by affirming that being on call as a live-in carer was almost a hybrid between work and rest, and that the on-call period of a live-in carer really did not neatly fall into either the principle of ‘work’ or the principle of ‘rest’ – it was a difficult decision. The Court affirmed that when push came to shove, and a choice had to be made on whether on-call was ‘work’ or ‘rest’, a period when someone was allowed to ‘sleep’ had to be deemed closer to ‘rest’ than ‘work’. As much as all of the factors about the live-in carer showed it was unpleasant, the Court just could not get over the fact that someone sleeping and snoring simply could not be said to be working. In short, Tomlinson Blake was not entitled to damages and to be paid at the minimum wage for the hours he spent ‘on-call’.

Ratio-decidendi:

‘73. The sleep-in worker who is merely present is treated as not working for the purpose of calculating the hours which are to be taken into account for NMW purposes and the fact that he was required to be present during specified hours was insufficient to lead to the conclusion that he was working’, Lady Arden

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.