Rittson-Thomas & Ors v Oxfordshire County Council [2021] UKSC 13 (23 April 2021)

Citation:Rittson-Thomas & Ors v Oxfordshire County Council [2021] UKSC 13 (23 April 2021).

Subjects invoked: 15. 'Contract'.11. 'Legal Methods'.

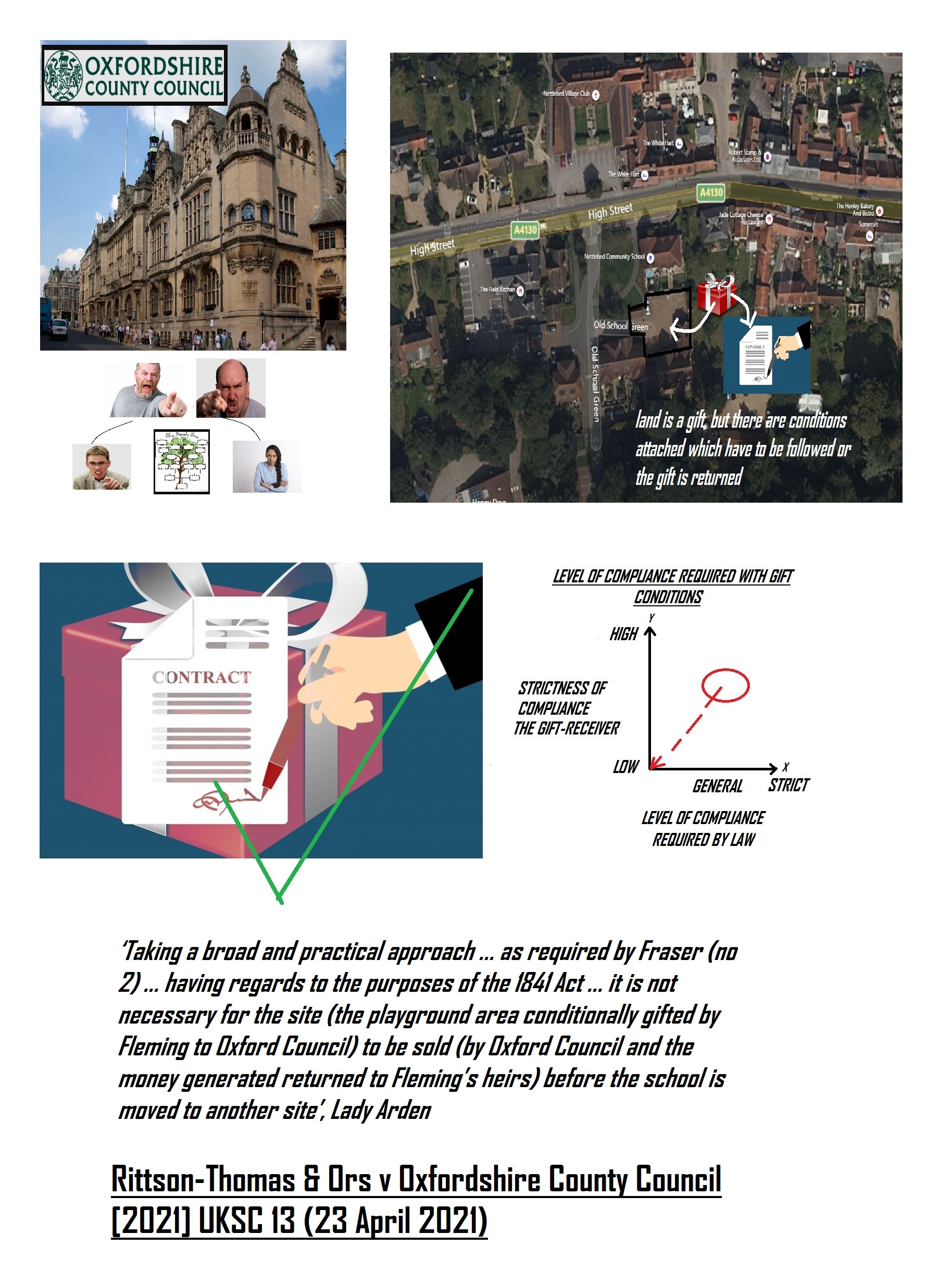

Rule of thumb:What happens if you make a gift to someone with a condition attached, and they breach the condition? Do you modern-day Courts have to apply the letter of the law for very old statutes? If a person breaks a condition of a gift, then typically they have to give it back, however, the strictness of this dilutes over time, and if they have largely followed the purpose of the condition then it is not breached. For older statutes, following the purpose of them is more important than following the letter of them.

Background facts:

This case invoked the subjects of contract and legal methods.

The facts of this case were that in 1914 and 1928 Robert Fleming made a conditional gift of land to Oxford City Council, which was running Nettlebed School. Fleming stated that he would gift Oxfordshire Council the land he owned beside the school on the condition that it would be used by the Nettlebed school in a productive way for recreation. Oxfordshire Council perfected the gift from Fleming by taking the land and using it productively for recreation within the school. Fleming died in 1933 and it was forever a sore point for his heirs that Fleming did this in his final years. In the late 1990’s there was a general plan across all many lands to sell school land, which was often in prime areas for new houses, and use the money to move to an area where land was cheaper, and use the excess money to renew all the building and improve in facilities. In 2007 Nettlebed school agreed to sell the land where the Nettlebed school was, and move Nettlebed school to a new location and a modern campus. Nettlebed were using the proceeds from the sale of the land to make the move to a newly built school campus with new facilities possible. Fleming’s modern day heirs, Rittson Thomas and others, told Oxford Council that they were in breach of the condition which they were given the land on, namely that they were only entitled to that piece of land if they used it for school recreation purposes, and did not just sell it. Fleming’s heirs wanted the money from the sale of the land. Oxford Council refused to give this Rittson-Thomas and the other heirs and so the matter went to Court.

The key principles in this case were the contract law principle of ‘conditional gift’, and the legal methods principle of ‘purposive vs. literal’ interpretations of statute. Rittson-Thomas and the others made a series of legal arguments to support their position about the land gifted to the school in 1914 and 1928 being returned to them. They argued that the principle of conditional gift applied strictly. They argued that where someone is given a gift based on them fulfilling a specific condition, and they do not fulfil this, then the gift is returned. They argued that the land gifted was not being used by the school in accordance with the condition any more, so it had to be given back to them. Rittson Thomas and the other heirs even supported this argument with a statute from 1841, The School Sites Act 1841, which in-point stated that if someone gifts land to a Council for use as a school, and the Council stops using the land as a school, and instead intends to sell it, then the land is to be returned to its original owner. They argued this was a water-tight case supported by a strict interpretation of both common law and statute. The Council argued that the principle of conditional gift was nowhere near as strict as Rittson Thoas were making out. They argued with a conditional gift a person is not required to follow overly strict conditions on a gift for an excessive period of time – they only need to follow conditions attached to a gift for a reasonable period of time. They further argued that they were not even in breach of the spirit of the condition of the gift, or the purpose of the 1841 Act. They argued that the land was not being sold and the school shrunk down in size as to make profits for councillors, which was the mischief the 1841 Act was seeking to prevent. They explained that all of the proceeds from the sale of the land were being reinvested in the new school facilities to be built, which was the spirit of the condition which Fleming gave the gift in, and was also in line with the purpose of the 1841 Act. The Council purposively reasoned that if the interpretation of the 1841 Act Rittson Thomas and the other heirs were taken was followed, this would actually make school conditions worse, and see money go into the hands of private people rather than go towards improving schools, and breach the purpose of the 1841 Act. They argued that this would be an absurd interpretation to take of this 1841 Act in breach of the Act’s purpose.

Judgment:

The Court upheld the arguments of the Council. They argued that to continue to strictly impose the conditions of the gift on the Council after 100 years would be excessive and arduous gift conditions which were not valid. The Court further held that given the age of the 1841 Act, a purposive interpretation of it had to be held over rather than a strict and literal one of it, in order for it to be applied to modern society. The Court affirmed that selling the land and relocating was within the purpose of the 1841 Act, which was that the Councils used the land they were gifted for the benefit of school pupils, rather than taking land, selling it and then have councillors pocketing the money, which was not happening in this case. Rittson-Thomas and the other heirs of Fleming were not entitled to the land or to the money generated from the sale of the land. Broadly speaking, the Court affirmed that if someone is given a conditional gift, then after 100 years of following these conditions, it is no longer reasonable to ask them to keep the conditions being strictly enforced by the exact letter of the conditions. The Court further held that with older statutes, such as a statute from 1841, where the purpose and the letter of the statute conflict, a purposive approach rather than a strict and literal approach has to be taken to the statute as a source of law - with older statutes people should only be expected to be in compliance with the purpose of them rather than strictly by the exact letter of the law.

Ratio-decidendi:

‘50. … The site of a school does not cease to be used for the purposes of the 1841 Act (section 2) where at all material times it is considered advisable to sell the site and, with the consent of the managers and directors of the school, if any, to apply the money arising from the sale in the purchase of another site, or in the improvement of other premises, used or to be used for the school (section 14). Taking a broad and practical approach to the statutory words, as required by Fraser (No 2), the power in section 14 … is to be interpreted as including a power of sale of the most usual kind, namely a power to sell with vacant possession. We think it implicit in the statutory words that, as on the facts of this case, the intention to use the sale proceeds, for the purchase of another site or in the improvement of other premises, must be present prior to, or at the time of, the school being permanently moved from the former site and at the time that that site is sold; but, out of an abundance of caution, we have inserted the words “at all material times” (which do not appear in the 1841 Act) to make this clear. … 51 … having regard to the purposes of the 1841 Act … it is not necessary for the site to be sold before the school is moved to another site and closed on the site given by the grantor’, Lady Arden at 50-51 ‘Taking a broad and practical approach … as required by Fraser (no 2) … having regards to the purposes of the 1841 Act … it is not necessary for the site (the playground area conditionally gifted by Fleming to Oxford Council) to be sold (by Oxford Council and the money generated returned to Fleming’s heirs) before the school is moved to another site’, Lady Arden

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.