R v Fylde Borough Council, on application of Oyston Estates Ltd [2021] UKSC 18 (14 May 2021)

Citation:R v Fylde Borough Council, on application of Oyston Estates Ltd [2021] UKSC 18 (14 May 2021).

Subjects invoked: 94. 'Planning 2 - Major Private Developments'.

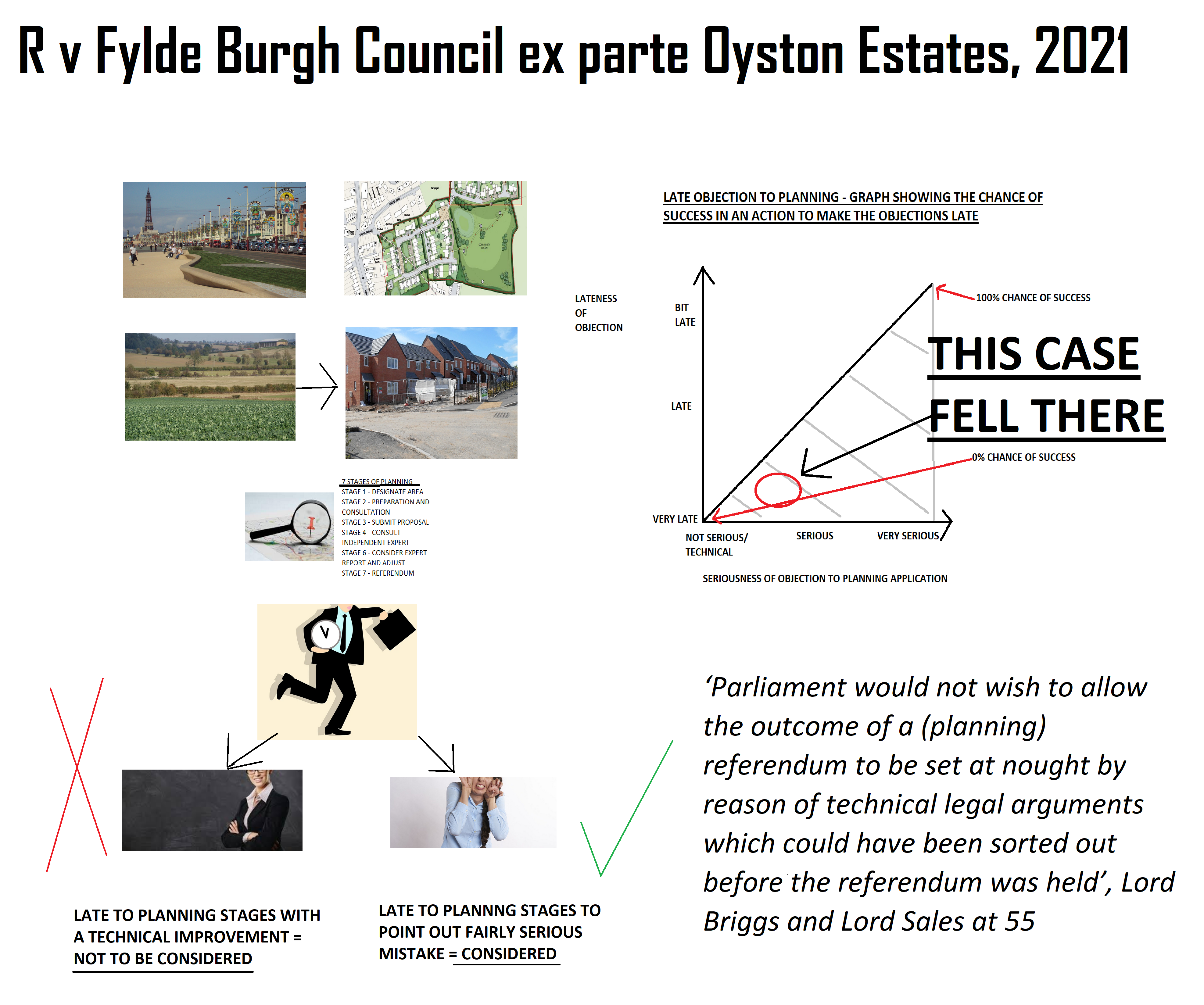

Rule of thumb:In planning matters, can you make submissions late? Yes, but there is a directly proportionate relationship between lateness of submissions and importance, and it is for the Court to consider this in the particular circumstances of the case.

The Court in this affirmed the principles of ‘strict statutory timelines in planning law taking precedence over the general rule of planning that technically legitimate objections only have to be made at some point before the end of the entire process’. This case affirmed that people nowadays in planning applications have to put in technical objections to planning decisions by Councils timeously in accordance with statute, and not just wait until later on in the process to correct any mistakes. It is only major mistakes in the planning process by Council that allow people to rely on the general rule that as long as objections are raised before the end of the process they are still valid. As the technical objection in this case was not within the time-limit it was not accepted as a valid objection, even although if it had been made on time it would likely have been accepted as valid and reasonable.

Background facts:

This case invoked the subject of major private planning developments & the principle of late submissions.

The facts of this case were that the Council for St Anne’s on the Sea, formally called Fylde Borough Council, in the Blackpool area was the subject of a ‘neighbourhood development plan’. This plan of the ‘St Anne’s on Sea Town Council’/Fylde Borough Council was to set the borders of an area for housing developers to be able to make new planning applications for new housing developments etc in the area. Debate grew over what the exact borders of this area for new housing developments should be. It was recognised that there had to be new land made available for new housing developments to take place on. However, it was also recognised that in drawing the borders there also had to be consideration of environmental considerations such as the wild life species, natural heritage, as well preserving an area of green/brown belt in the area. The issue was where exactly to draw the borders. Oyston Estates Ltd owned a lot of ground near the border of the proposed new neighbourhood development area. An independent examiner recommended that this farmland owned by Oyston Estates should be included within the borders of this area. This could have meant that Oyston Estates Ltd could have sold a lot of the farmland they owned for a lot of money to housing developers, rather than continue to be used for farming. The Council however decided that the border for new the development area should not extend as far as the land owned by Oyston Estates Ltd.

Oyston Estates Ltd sought to challenge this decision by the Council on the basis that the Council had not fully and properly taken the Independent Expert Report into consideration in making their decision. Oyston was able to make effective technical arguments – also supported by other environmental regulations - that the Council’s plans were not the best plans that could have been implemented using the expert’s advice. The Council argued that they had implemented the independent expert Report’s recommendations to a large degree, albeit not perfectly. The Council further argued that under the TCP Act 1990 s61(N) the time for Oyston to make this technical challenge to this particular part of the planning decision had expired as there had already been 90% support for it in a local referendum. Oyston argued that the general rule of planning was that an applicant could still successfully amend the planning decision if it was unreasonable provided the process was not yet finished. This legal debate got fairly detailed. It was established that there was a 7 part process to planning applications. Part 4 required an independent examiner to recommend the area in question. Part 5 required there to be a drawing of the border taking the expert report into account. Part 6 then required there to be a local referendum on the border decided. Part 7 then required a period for ordering the area. Oyston waited until after the referendum in Part 6 to make his valid technical objection, and when the Council refused to amend the area, the matter arrived at Court. The Court in this case held that there were 2 competing interests – one which was a public interest in having an efficient process, and another one which was to make sure that the planning decisions were right and fair to private parties.

Judgment:

The Court held that the middle ground and general rule of planning was that statutory time limits could be overruled if the objection was serious and made before the end of the planning process. The Court in this case held that the statute setting the timeline was sufficiently clear to overrule the objection in this case which was more technical in nature. The border of land for new housing developments and it did not extend as far as the land owned by Oyston Estates Ltd.

Ratio-decidendi:

'1. This appeal raises a single short point about the interpretation and effect of section 61N of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 (“the TCPA”), which is headed “Legal challenges in relation to neighbourhood development orders”. Its provisions apply also to legal challenges in relation to neighbourhood development plans, and it was to the making of such a plan that the legal challenge in the present case related. 2. Speaking generally, the making of neighbourhood development orders or plans requires the taking of what may loosely be described as seven consecutive steps, mainly by the relevant local planning authority. They are, in summary: (1) designating a neighbourhood area; (2) pre-submission preparation and consultation; (3) submission of a proposal; (4) consideration by an independent examiner; (5) consideration of the examiner’s report; (6) holding a local referendum; (7) making the order or plan'.

'55. ... The inference is that in enacting section 61N Parliament has balanced the potential competition between different public and private interests ... As has been observed in the case law, there are arguments on both sides of the debate regarding the alternative approaches to the timing of public law challenges. In section 61N Parliament has clearly adopted a particular solution which it considered appropriate in this particular context. ... with the aim of promoting public participation in certain decisions by holding referendums, Parliament would not wish to allow the outcome of a referendum to be set at nought by reason of technical legal arguments which could have been sorted out before the referendum was held. That would risk creating scepticism and disaffection with the new procedure which could undermine rather than promote public engagement. 56. For those reasons, although differing to a limited extent from the reasoning of the courts below, we would dismiss this appeal’, Lord Briggs

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.