Montgomery v Lanarkshire Health Board. Montgomery v Lanarkshire Health Board [2015] UKSC 1

Citation:Montgomery v Lanarkshire Health Board. Montgomery v Lanarkshire Health Board [2015] UKSC 1

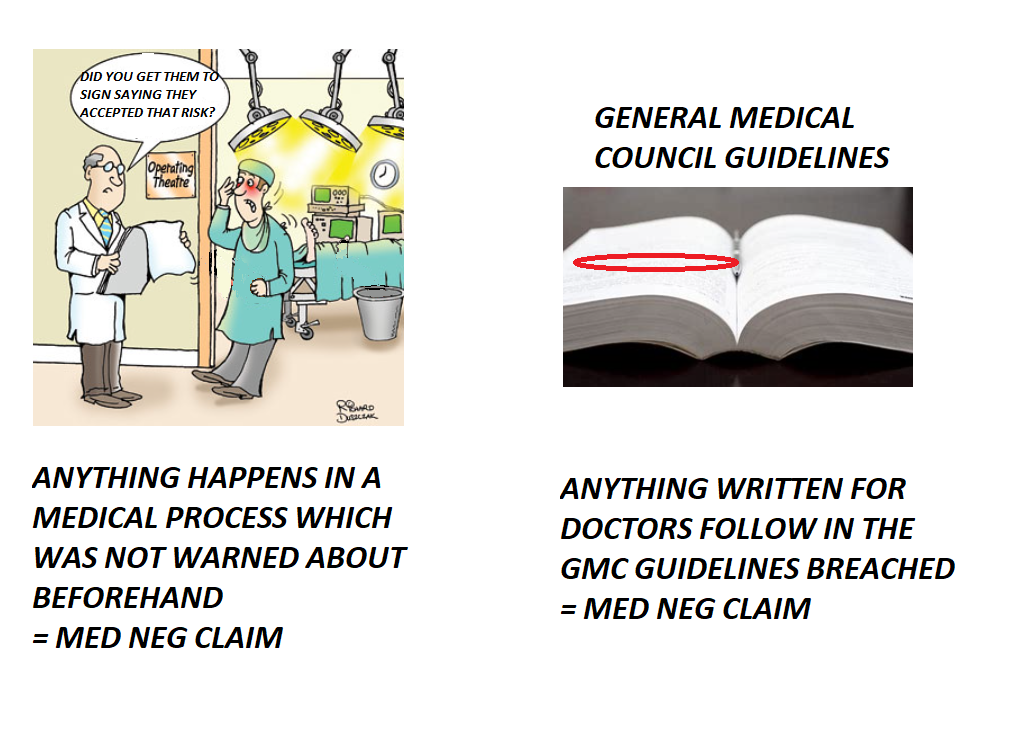

Rule of thumb:How do you raise a medical negligence action? This was an essential case in the field of medical negligence for 3 reasons. Firstly, the Court in this case held that the test of successfully suing a medical professional is essentially finding provisions in the General Medical Council guidelines that have been breached by a medical professional, and when a medical professional cannot justify their decision from these guidelines to a satisfactory level then negligence is established against them – the ‘therapeutic exemption’ defence of a groundswell of medical professionals in practice disagreeing with the GMC Guidelines, and following their own rules for their own clinically justifiable reasons, is no longer deemed to be compatible with the law. Secondly, it also confirmed that before anyone has any surgery or other treatment they must be provided with a full list of all the potential outcomes, no matter how remote, which only the patient can choose to ignore if they so wish. Thirdly, it affirmed that where any professional can be shown not to have followed guidance in a professional & respected textbook, this is the basis for a professional negligence action, even if other professionals in the industry do not follow the official guidance in relation to the practice point.

Background facts:

The factual circumstances of the case were tragic. A pregnant woman was type 1 diabetic meaning that there was a less than 10% chance her baby would be born with a slightly bigger head than normal, meaning that there could be complications in the delivery of the baby during labour. Before the woman opted against a Caesarean section she was not warned about this danger. There were complications during the natural delivery of the baby and the baby was unfortunately born with brain damage. .

Parties argued:

The approach to the woman was a practice followed by many doctors, but it contradicted by the GMC guidelines, so the doctor argued this was therefore not a breach of the law as it was a course of conduct followed by a number of professional doctors in practice thereby meaning that this textbook standard was the gold standard rather than the negligence standard.

Judgment:

The woman was successful in obtaining damages. The “therapeutic exception”, as it has been called, cannot provide the basis of the general rule and overrule actual formal medical textbooks.

d

Ratio-decidendi:

‘(85)... It follows that the analysis of the law by the majority in Sidaway is unsatisfactory, in so far as it treated the doctor's duty to advise her patient of the risks of proposed treatment as falling within the scope of the Bolam test, subject to two qualifications of that general principle, neither of which is fundamentally consistent with that test. It is unsurprising that courts have found difficulty in the subsequent application of Sidaway, and that the courts in England and Wales have in reality departed from it; a position which was effectively endorsed, particularly by Lord Steyn, in Chester v Afshar. There is no reason to perpetuate the application of the Bolam test in this context any longer. ... (86)...The correct position, in relation to the risks of injury involved in treatment, can now be seen to be substantially that adopted in Sidaway by Lord Scarman, and by Lord Woolf MR in Pearce, subject to the refinement made by the High Court of Australia in Rogers v Whitaker, which we have discussed at paras 77-73. An adult person of sound mind is entitled to decide which, if any, of the available forms of treatment to undergo, and her consent must be obtained before treatment interfering with her bodily integrity is undertaken. The doctor is therefore under a duty to take reasonable care to ensure that the patient is aware of any material risks involved in any recommended treatment, and of any reasonable alternative or variant treatments. The test of materiality is whether, in the circumstances of the particular case, a reasonable person in the patient’s position would be likely to attach significance to the risk, or the doctor is or should reasonably be aware that the particular patient would be likely to attach significance to it... (87) ... The first of these points has been addressed in para 85 above. In relation to the second, the guidance issued by the General Medical Council has long required a broadly similar approach. It is nevertheless necessary to impose legal obligations, so that even those doctors who have less skill or inclination for communication, or who are more hurried, are obliged to pause and engage in the discussion which the law requires. This may not be welcomed by some healthcare providers; but the reasoning of the House of Lords in Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] AC 562 was no doubt received in a similar way by the manufacturers of bottled drinks. The approach which we have described has long been operated in other jurisdictions, where healthcare practice presumably adjusted to its requirements. In relation to the third point, in so far as the law contributes to the incidence of litigation, an approach which results in patients being aware that the outcome of treatment is uncertain and potentially dangerous, and in their taking responsibility for the ultimate Page 30 choice to undergo that treatment, may be less likely to encourage recriminations and litigation, in the event of an adverse outcome, than an approach which requires patients to rely on their doctors to determine whether a risk inherent in a particular form of treatment should be incurred. In relation to the fourth point, we would accept that a departure from the Bolam test will reduce the predictability of the outcome of litigation, given the difficulty of overcoming that test in contested proceedings. It appears to us however that a degree of unpredictability can be tolerated as the consequence of protecting patients from exposure to risks of injury which they would otherwise have chosen to avoid. The more fundamental response to such points, however, is that respect for the dignity of patients requires no less... (95) Lord Kerr and Lord Reed

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.