Revenue and Customs v Tooth [2021] UKSC 17 (14 May 2021)

Citation:Revenue and Customs v Tooth [2021] UKSC 17 (14 May 2021)

Subjects invoked: 17. 'Administrative'.80. 'Taxation 1 - Income Taxes'.

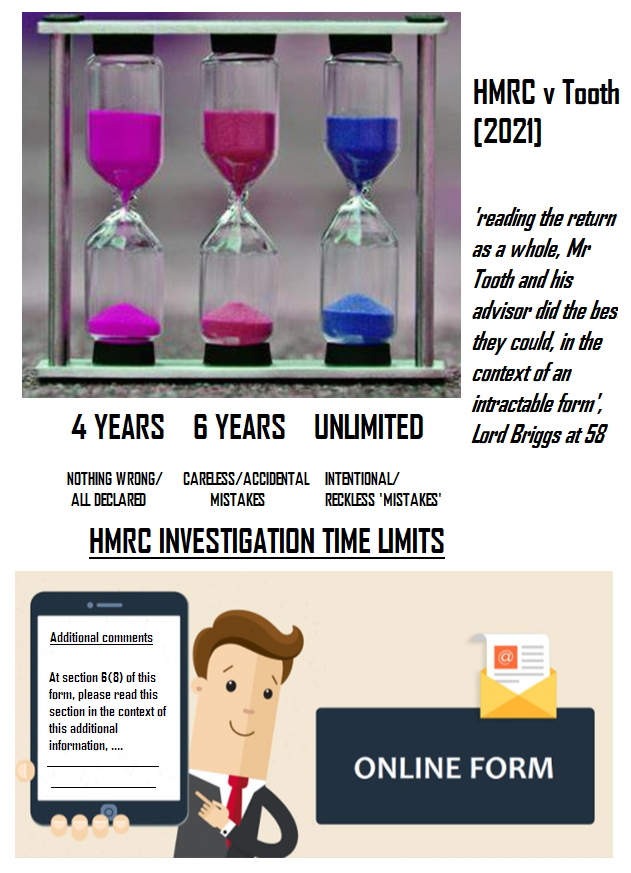

Rule of thumb:Is putting information in the ‘additional information’ box in Government forms rather than the one they are supposed to be in allowed? Yes, this is allowed and is still deemed to be a part of the form. This case further affirmed 2 different points of law. Firstly, it affirmed that tax returns have to be ‘read as a whole’ when considering whether they are accurate or not – one small part of a form filled out inaccurately for a good reason and then explained in the white box at the end does not make the form inaccurate. If due to the nature of a recommended electronic tax return software someone is unable to fill in a box in the tax return correctly, so they fill this box in wrongly and explain it correctly in an attachment at the end, then this is not deemed to careless or intentionally wrong information provided. Secondly, this case affirmed the meaning of ‘discovery’ tax cases. ‘Discovery’ cases are when there has been ‘an intention to mislead’ HMRC, either ‘deliberately or recklessly’, by the taxpayer in their form. ‘Discovery cases’ with an ‘intention to mislead’ never go ‘stale’ – they can still be raised by HMRC against someone 100 years+ after the tax form was put in. Forms people have filled in with no wrong information & full information where HMRC have ‘actual knowledge’ of a tax breach have to be raised within 4 years or they become ‘stale’, and forms with honest mistakes can become ‘stale’ after a requisite period of 6 years however - HMRC cannot chase ‘stale’ claims up after this period. The difference between an ‘honest’ mistake and ‘an intention to mislead’, or whether information is wrong at all, can raise debates however.

Background facts:

This case invoked the subjects of tax law & administrative law.

The facts were that in January 2009 Mr Tooth filled out his tax return using HMRC recommended software called ‘Iris’. Awkwardness/teething problems with the Iris tax return software system did not allow Tooth to accurately fill out his tax return in certain boxes. Tooth therefore filled in the boxes inaccurately but used the white empty box at the end of the form to explain the inaccuracies properly. Tooth also stated in this form to HMRC that he was using a tax avoidance/minimisation scheme which he believed was legal. This avoidance mechanism meant Tooth that reduced his tax by £500,000. ()An enquiry was commenced by HMRC in 2009 about this when Tooth informed them of the tax avoidance scheme in place but action was never taken against Tooth. In a ‘test-case’ against someone else in 2013 it was stated by the UK Supreme Court that the type of tax-avoidance scheme used by Tooth in 2009 was a breach of tax law and that people operating this scheme should be investigated and required to pay more tax to HMRC. HMRC therefore had a desire to raise tax proceedings against Tooth because they knew there were 99.9% to win the case, and Tooth wanted to stop these proceedings from being able to be raised on the grounds it was ‘stale’.

The foundational legal position about when tax cases go stake was agreed by both parties - where accurate financial information has been provided to HMRC the time limit for them to raise a case is 4 years; where financial information has been provided to HMRC that is accidentally wrong then this is deemed to be ‘carless’, and HMRC have 6 years to raise this case; where there is financial information that is deliberately or recklessly wrong then this is called ‘discovery’ and there is no time limit for HMRC to bring the case against the taxpayer. () In 2013 at the time of the UKSC Judgement the 4 year time limit for HMRC to subject Tooth to tax proceedings if he had provided no wrong information had expired. The only way Tooth could be made liable for the unpaid tax was if careless or reckless/deliberate behaviour could be shown by Tooth in the form to increase the time period.

The debate between the parties was over whether Tooth had filled in his tax form carelessly or recklessly/deliberately wrongly. It was agreed that Tooth had consciously filled out the wrong information meaning that the question was whether this was deliberately wrong information provided by Tooth. HMRC argued that the general test for information being deemed to be intentionally wrong is where the information categorically is completely 100% wrong. It is not intentional but careless if the information is in the general ball-park of being right but not spot-on.

HMRC argued that Tooth filling in wrong information in the box meant that this part of the form was categorically 100% wrong and this therefore constituted intentional inaccuracy. HMRC explained that as this was categorically wrong it flung off all of their investigation methods. HMRC argued that explaining categorically wrong information in the white box at the end did not stop the earlier part of the form meeting the ‘intentional inaccuracy’ requirement to raise the case. HMRC therefore concluded that the discovery principle applied to reopen the tax case against Tooth – and make Tooth pay the 500k bill. Tooth argued that even although this part of his form was inaccurate, because he had explained this part of form accurately in the box at the end this ensured that the form was not filled out inaccurately. Tooth argued that when his form was read as a whole the form was not inaccurate at all, let alone carelessly, recklessly or deliberately inaccurate. Tooth therefore took the position that because he explained the form correctly at the end this could not be said to be done wrongly and his form was indeed filled in carefully.

Judgment:

The Court upheld the arguments of Tooth. The Court held that disclosing wrong financial information in the wrong box due to a software anomaly but explaining it properly in the white box afterwards, which this box in the form is for, did not constitute careless inaccuracy or deliberate/reckless inaccuracy by Tooth. The Court also took into account that the use of the white box at the end by Tooth was for a good reason – it was by and large unavoidable due to inherent software ineffectiveness in HMRC recommended software, rather than Tooth just being deliberately difficult and awkward with his form for the sake of it.() The Court did take the opportunity to further clarify that there is no principle of ‘staleness’ in UK tax law in regards to ‘discovery’ cases. If a tax officer ‘discovers’ a deliberate mistake in a tax return there is no time limit for HMRC to bring it – a ‘discovery’ case never goes stale – but the case against Tooth was not a ‘discovery’ case because Tooth’s error was not deemed to be intentional or careless. HMRC’s case for the tax-avoidance scheme against Tooth was ‘stale’ as it was outside the 4 year window and Tooth did not have to pay the £500,000 from his tax-avoidance scheme.

Ratio-decidendi:

‘It may be convenient to encapsulate this conclusion by stating that, for there to be a deliberate inaccuracy in a document within the meaning of section 118(7) there will have to be demonstrated an intention to mislead the Revenue on the part of the taxpayer as to the truth of the relevant statement or, perhaps, (although it need not be decided on this appeal) recklessness as to whether it would do so’. Lord Briggs and Lord Sales at 47 ‘That cannot be right. Reading the return as a whole, Mr Tooth and his advisors did their best, in the context of an intractable online form which did not appear to enable them to do it more directly, to explain the employment-related and scheme-derived basis of his ambitious claim to extinguish his 2007-8 tax liability by an admittedly contentious carry-back’, Lord Briggs and Lord Sales at 58 ‘In our judgment, contrary to the latter part of para 37 in the decision in Charlton, there is no place for the idea that a discovery which qualifies as such should cease to do so by the passage of time. That is unsustainable as a matter of ordinary language and, further, to import such a notion of staleness would conflict with the statutory scheme’, Lord Briggs and Lord Sales at 76. ‘For the reasons we have given, we would dismiss the Revenue’s appeal seeking to uphold the validity of the discovery assessment made in respect of Mr Tooth. Mr Tooth does not fall within the scope of the condition set out in section 29(4) of the TMA. The situation mentioned in section 29(1) was not brought about deliberately by him’. Lord Briggs and Lord Sales at 87. ‘Reading the return as a whole, Mr Tooth and his advisors did their best, in the context of an intractable online form which did not appear to enable them to do it more directly, to explain the … scheme’, Lord Briggs and Lord Sales at 58

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.