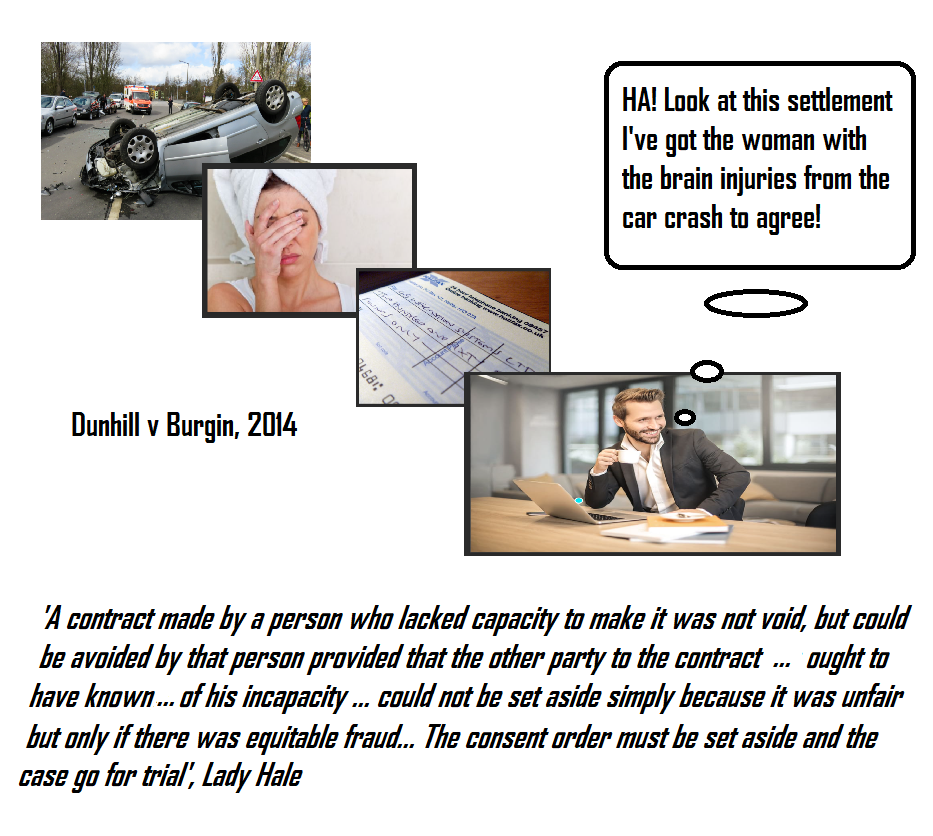

Dunhill v Burgin (Rev 1) [2014] UKSC 18 (12 March 2014)

Citation:Dunhill v Burgin (Rev 1) [2014] UKSC 18 (12 March 2014)

Rule of thumb:Where someone has had a brain injury, which the other party knows about, any deals they enter with them which are particularly shockingly bad deals for them financially, can they be set aside on grounds of incapacity? Yes, contracts with vulnerable people which are off-the-spectrum bad deals for them are not enforceable. UK law protects vulnerable from extremely bad deals – in other words if a person without a brain injury entered this, they would not be protected from negotiating a bad deal, but vulnerable people are protected from negotiating a bad deal.

Background facts:

The basic facts of this case were that Dunhill was involved in a car accident and suffered a brain injury. She initially conducted the claim herself and later instructed a litigation friend to negotiate the claim for her, and a settlement of around £12,500 was agreed for her claim. However, Dunhill's claims was worth around 100 times more than this, meaning she had lost 1 million pounds. Some time after this settlement Dunhill tried to argue that this settlement was invalid and wanted more compensation, but Burgin refused to accept this claiming the matter was over with liability discharged.

Parties argued

Dunhill sought a Court declaration to have this settlement declared null and void on the grounds of of incapacity. The very fact that such a woeful settlement was achieved was provided by Dunhill as evidence of this lack of capacity - no person with any real capacity could have negotiated such a low settlement in this case was one of the arguments. Burgin argued that Dunhill had a brain injury that affected her ability to think but she still had an ability to think to some degree and was clearly far from insane - it was clear from the medical evidence she had a lot of capacity, even if not full. Moreover, they argued that the litigation friend was perfectly sane and should have sought professional legal advice, meaning that this person was responsible rather than them. Burgin argued that the combination of a woman who lacked some capacity but still had a decent level of understanding, societal awareness and cognitive ability, combined with a litigation friend to help her, did not lack capacity to contract under the normal test. Burgin provided a lot of authority to argue that there was sufficient capacity between the woman and the litigation friend to reach a settlement.

Judgment:

The Court upheld the arguments of Dunhill. The Court stated that where one of the parties knows the other party has limited capacity, and is aware that they are entering a contract which is beyond atrocious for them, then the law of capacity does prevent this person who is aware of what a bad deal it is for the limited person from entering this grossly undervalued contract. The Court held that when it comes to people with limited capacity others are not allowed to enter contracts with them which are beyond a bad deal for them. In order for the contract with a person of limited capacity to be valid it has to be on the spectrum of at least being a distinctly mediocre and very unfavourable contract, rather than an utterly atrocious one which is off the charts laughably bad. In this case if the settlement had been 200,000 or so, a very bad settlement rather than absolutely atrocious one, it may have been more debatable. The Court allowed this settlement to be set aside on a lack of capacity in the harrowing circumstances of this case.

Ratio-decidendi:

‘In Imperial Loan Co Ltd v Stone [1892] 1 QB 599, the Court of Appeal held that a contract made by a person who lacked the capacity to make it was not void, but could be avoided by that person provided that the other party to the contract knew (or, it is now generally accepted, ought to have known) of his incapacity. As Mr Rowley points out on behalf of the defendant, this rule is consistent with the objective theory of contract, that a party is bound, not by what he actually intended, but by what objectively he was understood to intend. The rule in Imperial Loan was applied by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in Hart v O'Connor [1985] AC 1000, a case from New Zealand, where the issue was whether this only applied if the contract was fair. Overruling prior New Zealand authority to the contrary in Archer v Cutler [1980] 1 NZLR 386, but consistently with the decision of the High Court of Australia in McLoughlin v Daily Telegraph Newspaper Co Ltd (No 2)(1904) 1 CLR 243, the Board held that a contract made by a person who was ostensibly sane could not be set aside simply because it was unfair but only if there was equitable fraud which would also avail a sane person. This rule, it is argued, applies just as much to the settlement of civil claims as it does to any other sort of contract... I would therefore dismiss both appeals and uphold the order made by Bean J. On the test properly to be applied, Ms Dunhill lacked the capacity to commence and to conduct proceedings arising out of her claim against Mr Burgin. She should have had a litigation friend from the outset and any settlement should have been approved by the court under CPR 21.10(1). We have not been invited to cure these defects nor would it be just to do so. The consent order must be set aside and the case go for trial’, Lady Hale, 'A contract made by a person who lacked capacity to make it was not void, but could be avoided by that person provided that the other party to the contract (or ought to have known) of his incapacity ... could not be set aside simply because it was unfair but only if there was equitable fraud... The consent order must be set aside and the case go for trial', Lady Hale

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.