Royal Mail Group Ltd v Efobi [2021] UKSC 33 (23 July 2021)

Citation:Royal Mail Group Ltd v Efobi [2021] UKSC 33 (23 July 2021).

Subjects invoked: 9. 'Evidence'.38. 'Discrimination'.

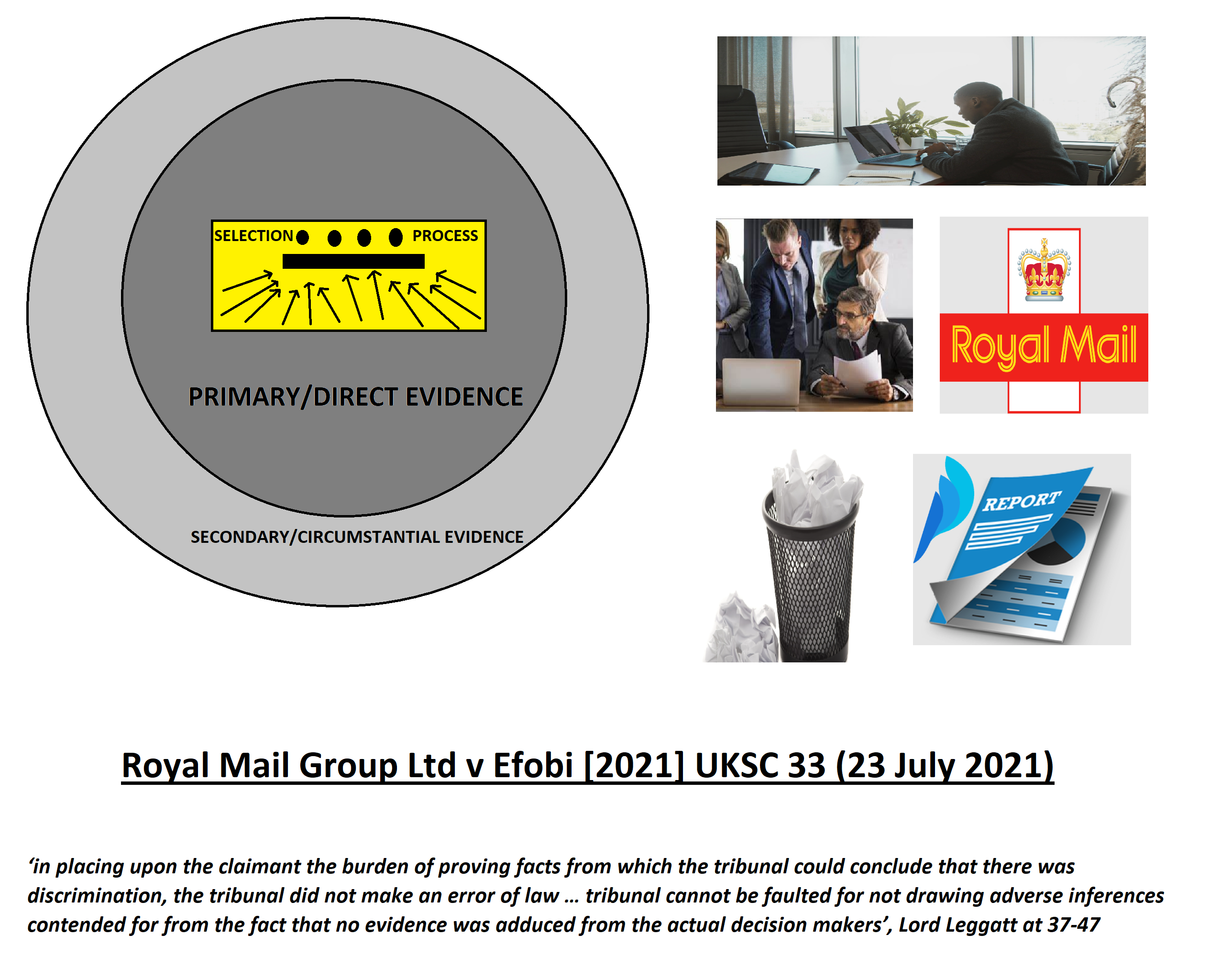

Rule of thumb:If you do not bring ‘best evidence’ before the Court in a litigation, are you still allowed to run the case to trial? No, the Court must not allow you to run the case to trial if you do not bring best evidence & withhold best evidence from the Court. The Court affirmed that if a person only leads circumstantial/secondary evidence in a case about an alleged breach of the law, and does not lead direct/primary evidence about this, then this claim will not be deemed to have removed the burden of proof. If a person is alleging discrimination in a job selection process, and only leads an expert report based on their own applications and statistics, rather than the full details of the actual selection process – all the candidates and CV’s – then this will not provide the basis for a successful discrimination claim.

Background facts:

This case invoked the subjects of discrimination law and the law of evidence.

The facts of this case were that Mr Efobi went to University and obtained graduate and postgraduate qualifications in IT systems. After graduation rather than Efobi spend many months unemployed searching and applying for graduate-entry jobs, Efobi was keen to start working more or less any job and making money as soon as possible, and then applying for graduate positions from there. So Efobi started working for Royal Mail at the grassroots level as a postman. Royal Mail had vacancies for management positions within Royal Mail which related to IT systems, and they advertised these on job websites. Efobi applied for around 30 of these jobs, explaining how he had ground-level experience in Royal Mail and also technical expertise through his university qualifications, which he believed made him perfect for the positions. However, his applications were unsuccessful.

Efobi was perplexed and somewhat annoyed/disillusioned about his job applications being refused. Efobi showed the CV and application forms he submitted to Royal Mail to an expert employment consultant. Efobi sought an explanation from employment consultants about what he could to improve his cv, applications and job prospects. These employment consultants informed Efobi that they did not understand his applications being refused. Efobi then obtained a formal report affirming that employment consultants could not understand how his applications were refused. Efobi arrived at the conclusion that his applications to Royal Mail must have been refused because he was black. Efobi informed Royal Mail that he was looking for damages for discrimination, but Royal Mail refused, so the matter went to Court.

Efobi argued that the principle of ‘competency’ in evidence law applied in this matter. ‘Competency’ means that before any facts can be referred in any matter some form of evidence has to be presented. Efobi presented the job adverts, his CV and his rejected applications forms along with an expert report from an employment consultant in this matter, with the employment report suggesting that there was not a single objective reason he could think of as to why Efobi would not have got the job. Efobi then argued that if there was no objectively justifiable reason for him not getting the reason, the reason he did not get the job could only be because he was black – Royal Mail had essentially got a ‘bad vibe’ off of Efobi because he was black, and did not care about his competences and qualifications for the job. Efobi further presented laws to show that a person being denied a job due to the colour of their skin was a breach of discrimination law entitling him to damages.

Royal Mail argued that the principle of ‘burden of proof’ applied in this matter. ‘Burden of proof’ means that the facts in a matter have to be inferred from primary evidence, or no facts can be inferred in a credible and reliable way. Royal Mail argued that there had been no evidence led by Efobi about the other candidates who actually got the job ahead of him, only circumstantial evidence. They argued that only presenting secondary evidence, and not primary evidence, in such an important matter, failed to remove the burden of proof. Royal Mail also argued that the principle of ‘adverse inference’ did not apply in this case to the fact that they had not explained why other people got the job ahead of Efobi. They argued that they had not refused to provide the evidence about the other candidates who got the jobs ahead of Efobi. They argued that this principle only applies when the pursuer has requested the evidence and it has been refused, or where the person bringing the case has made a case that could be accepted by the Court.

Judgment:

The Court upheld the arguments of Royal Mail in this matter. They affirmed that the burden of proof principle did apply in this matter to ensure Efobi’s case could not be upheld. The Court affirmed that Efobi did not have the weight of evidence needed to infer the facts about racism/discrimination by Royal Mail in the job application process that he was claiming, because he was only presenting secondary/circumstantial evidence speculating about what may have happened in the selection process, rather than direct/primary evidence of what did actually happen in the selection process.

The Court affirmed that before anyone can successfully raise a case about discrimination in applications for jobs they have to provide the primary evidence of the actual selection process - the other candidates’ CV’s, application forms and interviews who they were competing against for the job, and infer facts from these. The Court explained that the circumstantial evidence presented by Efobi did not allow them to infer the facts about discrimination which Efobi claimed. The Court also affirmed that the ‘Adverse inference’ principle did not apply to the failure of Royal Mail to provide this evidence from the interview process themselves. They affirmed that where an accusation is made against someone, and they are not asked to provide the evidence, then there is no negative inference to be drawn from their failure to produce the evidence. In other words, if Efobi had requested the full details of the selection process and then Royal Mail refused to provide it this, this would have invoked the principle, but Efobi did not.

(Although Efobi lost, this was a case which has moved discrimination in job applications a lot further down the road. It has affirmed that employers cannot be subjective about the new employees they take on after inviting job application – they have a legal duty take the person who is objectively the best for the job, and not the person whose face fits – they cannot decide applications on ‘just getting a good vibe’ or ‘just getting a bad vibe’).

Ratio-decidendi:

Lord Leggatt, Ratio Decidendi at 37-47 ‘37. The critical point for present purposes is that, in placing upon the claimant the burden of proving facts from which the tribunal could conclude (in the absence of any other explanation) that there was discrimination, the tribunal did not make an error of law… 47. In the circumstances the employment tribunal cannot be faulted for not drawing the adverse inferences contended for from the fact that no evidence was adduced from the actual decision-makers. Furthermore, even if those inferences had been drawn, they would not have enabled the tribunal properly to conclude that the burden of proof had shifted to Royal Mail. I agree with the Court of Appeal that, if the claimant had surmounted that hurdle, the absence of evidence from the decision-makers may have placed Royal Mail in difficulty in proving that there was no racial discrimination. I also, however, agree with the Court of Appeal’s conclusion (at para 59 of the judgment) that there was plenty of evidence to support the employment tribunal’s finding that there was no prima facie case of discrimination and that the tribunal was manifestly entitled to dismiss the claim on that basis’,

‘in placing upon the claimant the burden of proving facts from which the tribunal could conclude that there was discrimination, the tribunal did not make an error of law … tribunal cannot be faulted for not drawing adverse inferences contended for from the fact that no evidence was adduced from the actual decision makers’, Lord Leggatt at 37-47

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.