JTI POLSKA Sp. Z o.o. & Ors v Jakubowski & Ors [2023] UKSC 19 (14 June 2023)

Citation:JTI POLSKA Sp. Z o.o. & Ors v Jakubowski & Ors [2023] UKSC 19 (14 June 2023)

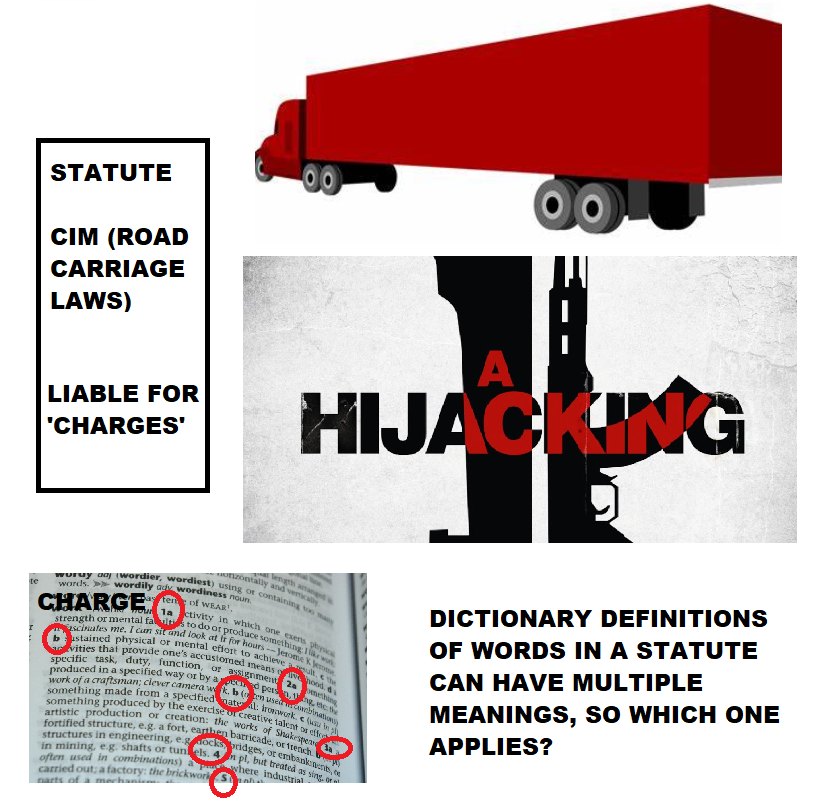

Rule of thumb 1:If a truck driving company loses cargo/ has it stolen, and a Regulatory agency fines the owners/sellers of the cargo a massive baulking amount, is the truck driving company liable to pay this fine? Yes, this falls under ‘charges’ in the carriage by road statute and the truck drivers have to cover the money for the fine paid.

Rule of thumb 2:If there is a past case which the Court is not sure if it is correct or not, should they apply it? Yes, especially if the case has been in existence for a long time and the legislature has not introduced provisions to overturn it, and before a Court considers doing they must be sure it is definitely wrong rather than unsure/ambivalent.

Rule of thumb 3:If there are 2 definitions which can be taken of a word in a statute, a narrow one and a broad one, which make the statute mean different thigs, what definition should the Court follow? This is at the discretion of the Court, although if there is past case-law on it then this should be followed.

Background facts:The basic facts of this case were that the first party were Polish truck drivers, and the second party were Polish cigarette wholesalers. The Polish cigarette wholesalers sold cigarettes from their warehouse with a value of £72k to a retailer in the UK. The cigarette wholesalers paid for the Polish truck drivers to transport this by road to the company in the UK. Once the truck-drivers reached the UK, they parked up their truck, but it was then broken into by thieves in the UK who stole the £72k of cigarettes. Under EU law the wholesaler was deemed to only owe the excise duty to the EU once it safely reached the retailer in the UK, and if it did not reach its destination, a £450k fine was owed. The wholesaler agreed to pay for the £72k of lost cargo, but refused to pay the £450k fine.

Parties argued:The wholesaler referred to a rule in the Convention on the Contract for the International Carriage of Goods by Road 1956 (the "CMR")which said that ‘other charges’ incurred could be claimed by negligent truck driving. The wholesaler also provided an in-point case to support this which deemed that the truck drivers owed the fine for the damages as well. The term charges can have 2 meanings – a narrow one and a broad one – with charges narrowly meaning all the private sector costs required to complete a task, and charges broadly meaning all criminal, tax, regulatory etc charges. The truck driver argued that this case affirming this position was a wrong overly-broad interpretation of the meaning of the ‘charges’ word in the rules. The truck drivers further argued the proximity of damage and argued that this was too far removed to be a valid ground – if they had known about this risk then they would have purchased insurance to cover it and not left themselves open to it.

Court held:The Court affirmed that the decision applied. The Court did express some concern with the law in the area & how it fitted in with the remoteness of damages principles, however, explained that the decision was not so obviously unfair that it should be overturned, as there were reasons for why this law was effective to motivate truck companies to prioritise the deterrence of crime when delivering goods to stop black markets for genuine goods emerging, and that there had been no new legislation introduced to overturn this case-law decision. The Court affirmed the importance of Judges following case-law even if they think the decision was harsh and not one they would have made. The truck drivers were therefore ordered to pay the £450k fine.

Ratio-decidendi:

‘The main point made there was the uncertainty in the law resulting from the fact that the broad interpretation potentially allowed losses which would be too remote as a matter of English law to be recoverable and, to address this problem, encouraged the inappropriate adoption of national law standards, as was done by the first instance judge in Sandeman. As already explained, in practice this has not proved to be a problem. The charges which have been held to be recoverable under the broad interpretation have been reasonably foreseeable. The only example which the parties have identified in the caselaw over the past 45 years in which remoteness was an issue is Sandeman and the Court of Appeal decision in that case was that the claim was not one for charges. The appellants also relied on the uncertainty created by the Sandeman decision as to the status of Buchanan in the light of the Court of Appeal’s statement that it should not be “applied any more widely by the courts of this country than respect for the doctrine of precedent requires”. Any uncertainty thereby created was, however, the result of this inappropriate statement by the Court of Appeal rather than the decision in Buchanan. That statement should not have been made and should not be followed. The appellants further relied on the uncertainty exemplified by the decision in Sandeman which they characterised as a legally unsatisfactory decision driven by a desire to avoid the consequences of applying the broad interpretation. It is not necessary for the purpose of this appeal to determine whether or not Sandeman was correctly decided. It is sufficient to point out that it concerned very special facts… Reversing Buchanan is not going to achieve that. To do so it would be necessary to amend article 23.4 through a Protocol, as was done for CIM. If that was to be done there would be much to be said for adopting a similar approach to CIM so that the same liability regime applied throughout any combined transport. That, however, is a matter for the parties to the CMR’, Lord Hamblen at 112-114 & 120

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.