Canada Square Operations Ltd v Potter [2023] UKSC 41 (15 November 2023)

Citation: Canada Square Operations Ltd v Potter [2023] UKSC 41 (15 November 2023)

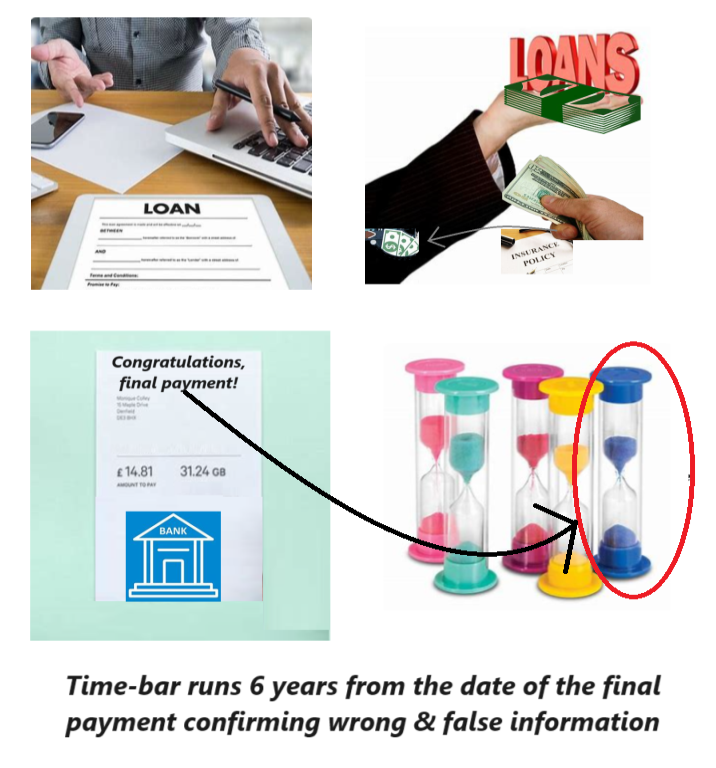

Rule of thumb: Stare-decisis: In a commercial action does time-bar run from the end of the agreement where the wrongful act was done? As a general rule, yes, however, as an additional exception, it can also be argued that the time-bar only runs from the point of the person finally admitting their wrongdoing, meaning the time-bar limit date can be limitless.

Background facts: The facts of this were that in 2006 Potter, a debtor, borrowed money from a Canada Square bank (the creditor) totalling around £20,000. This £20k included the initial lump sum, interest on that, and a default insurance of £3k. The loan was finally completed between debtor & creditor in 2010. In 2014 the bank, Canada Square, admitted in a different loan case raised that in the payments they took and gave to insurers, they took a very large secret commission on this, of around 50%.

Parties argued:Mrs Potter sued Canada Square in 2018 claiming that she wanted all the secret commission paid to her as this was a breach of agency law.

Canada Square admitted that they sent Mrs Potter wrong paperwork in 2010 not outlining the commission properly, but that this time-barred in 2016, 6 years after the loan was completed in 2010.

Court held: The Court held that the case was not time-barred. The Court held that where a party has provided incorrect information to another party, concealing that they broke the law towards them, the 6 year time-bar limit runs from the point when the person actually finally provided correct information affirming the truth of the facts about them possibly breaking the law. The Court held that Canada Square did this in 2014, so the time-bar date would be in and around 2020, so Mrs Potter’s case was not time-barred.

Ratio-decidendi:

1. ‘This appeal raises fundamental questions concerning section 32(1)(b) and section 32(2) of the Limitation Act 1980 (“the 1980 Act”). Section 32(1)(b) postpones the commencement of the ordinary limitation period where “any fact relevant to the plaintiff’s right of action has been deliberately concealed from him by the defendant”. Section 32(2) provides that, for the purposes of section 32(1), “deliberate commission of a breach of duty in circumstances in which it is unlikely to be discovered for some time amounts to deliberate concealment of the facts involved in that breach of duty”.

2. The questions raised in the appeal concern the meaning of the phrases “deliberately concealed”, in section 32(1)(b), and “deliberate commission of a breach of duty”, in section 32(2).

1. The facts: 3. On 26 July 2006 the claimant, Mrs Potter, entered into a loan agreement with the defendant, Canada Square Operations Ltd, then known as Egg Banking plc. The agreement was constituted by a pre-printed standard form prepared by the defendant and signed by both parties, and was a credit agreement within the meaning of the Consumer Credit Act 1974 as amended (“the 1974 Act”). It stated that the total amount of credit was £20,787.24, comprising a cash amount of £16,953.00 and a payment protection premium of £3,834.24. That premium related to the claimant’s purchase of a payment protection insurance policy (“the PPI policy”). The loan was repayable in instalments over a period of 54 months.

4. As well as being a commercial lender, the defendant was also an insurance intermediary. Over 95% of the amount described in the agreement as the payment protection premium constituted the defendant’s commission on the PPI policy. The sum paid to the insurer was only £182.50. The defendant did not inform the claimant that it would receive or retain commission on the policy.

5. The claimant completed the payments under the agreement early, and the agreement came to an end on 8 March 2010.

6. In November 2014 this court gave judgment in the case of Plevin v Paragon Personal Finance Ltd [2014] UKSC 61; [2014] 1 WLR 4222 (“Plevin”). It held, on facts similar to those of the present case, that the non-disclosure of a very high commission charged to a borrower made the relationship between the creditor and borrower “unfair” within the meaning of section 140A of the 1974 Act, with the consequence that the borrower could seek a remedial order under section 140B.

7. In April 2018 the claimant complained to the defendant that the PPI policy had been mis-sold to her…

154…. The defendant deliberately concealed those facts from her, as the recorder held, by consciously deciding not to disclose the commission to her. Although section 140A was not in force when that decision was initially taken, with the result that the facts concealed were not relevant to a right of action at that time, the defendant continued to withhold the information from her after section 140A was brought into force in respect of pre-existing agreements (see para 32 above), while the credit agreement remained in force and the commission continued to be paid. The claimant did not discover the concealment until November 2018, shortly before commencing these proceedings. It is not suggested that she could with reasonable diligence have discovered the concealment any earlier. The requirements of section 32(1)(b) are accordingly met.

155. So far as section 32(2) is concerned, it follows from Cave, as has been explained, that it must be shown that “the defendant knew he was committing a breach of duty, or intended to commit the breach of duty” (as Lord Scott said at para 60). It is conceded that that test cannot be met in the circumstances of the present case. The basis of the concession, as I understand it, is that although the defendant deliberately decided not to disclose the commission, and must have been aware that there was a risk that by doing so it was making its relationship with the claimant unfair within the meaning of section 140A of the 1974 Act, it has not been shown that it knew or intended that the non-disclosure would have that effect. Accordingly, although its failure to disclose the commission gave rise to the claimant’s right of action, and can therefore be regarded as a breach of duty for the purposes of section 32(2), it cannot be shown that the defendant knew that it was committing a breach of duty or intended to do so.

9. Conclusion: 156. Although I find myself in respectful disagreement with the reasoning of the Court of Appeal, I conclude that it was correct to hold that the defendant was deprived of a limitation defence by the operation of section 32(1)(b) of the 1980 Act, although it wrongly held that the defendant was also deprived of such a defence by the operation of section 32(2). It follows that the claim is not time-barred and that the defendant’s appeal should be dismissed’.

Lord Reed

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.