Potanina v Potanin [2024] UKSC 3 (31 January 2024)

Citation:Potanina v Potanin [2024] UKSC 3 (31 January 2024)

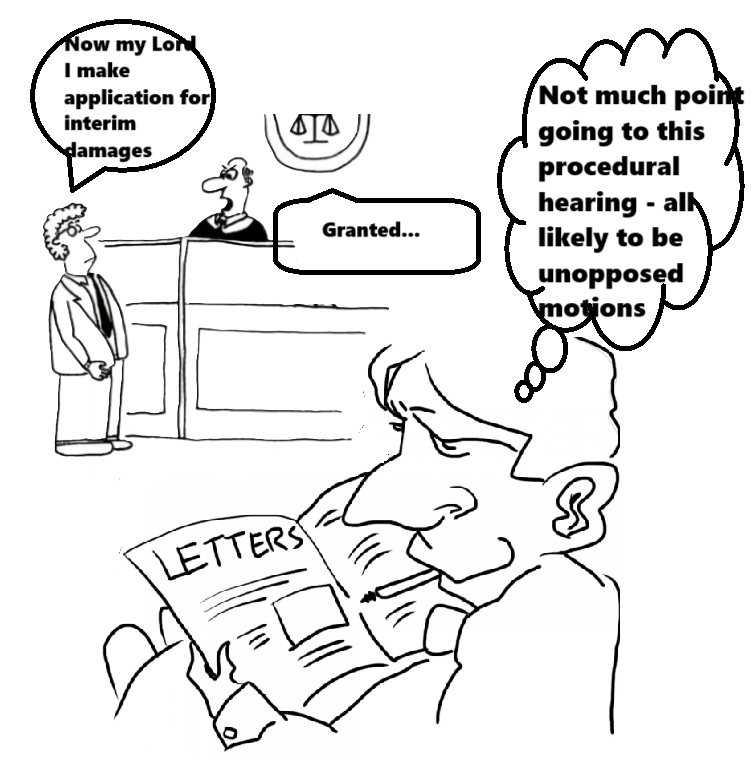

Rule of thumb: In procedural hearings before a trial, if one of the parties is making an application for an important procedural step, does prior written warning of this have to be provided? Yes, if there are important procedural motions in a case, prior written notice of them has to be provided (clearly & expressly and not in vague terms), so that the other party can go to the Hearing prepared for this. If this is not provided then the procedural decision must be reduced & considered again.

Background facts:The basic factual matrix were that Potanin & Potanina were formerly husband & wife but were going through a divorce. The estate of Potanin was worth billions of pounds & most of his money was tied up in company shares so it was difficult to value & obtain it. There was a procedural Hearing called in the case under the Matrimonial and Family Proceedings Act 1984. Only Potanina turned up and Potanin did not. Potanina made an application for interim financial relief – payments of money per month to be paid to her - at the bench, which was founded upon well-researched laws & so the remedy she was seeking was granted. There was no one there on behalf of Potanin to argue against this.

Parties argued: This matter revolved around the principle of ‘fair notice’. Normally, it is obvious whether notice has been provided, but in this case it was not. Potanina argued that Potanin had been provided with fair notice of the hearing – because as a point of law application for a financial relief Hearing to be arranged could be made as a clearly written point of law in the 1984 Act. Potanina further argued that she had made the standard application for interim relief, with applications like this standard in these procedural hearing requiring no express notice of it required to be given with there being implicit notice of it in the Act & in case-law, this was put to Potanin’s empty seat at the hearing, and it was not stated that it was objected to.

Court held: This raised a difficult point of law over fair notice – which is a cornerstone principle of procedural law – the parties have to be provided with fair notice in writing of the person’s case factually & legally. This raised the sub-principle within fair notice of explicit fair notice in a letter & implicit fair notice of the potential for the application to be made a point of law in statute & case-law. On the one hand, the Court did not want to be seen to be allowing people to get away with not turning up for hearings to oppose standard motions/applications like interim financial relief in divorce proceedings, which there was implicit notice of purely from the calling of the Hearing & reference to the Act – every single point & application does not have to put expressly in writing – many are implied by reference to statute & case-law. However, on the other hand, given the size of the financial settlement involvement involved, it was deemed that this was an application which had to be made in writing with express notice of it provided. The matter was remitted back to the family Court so that Potanin could object to the interim financial relief payments Potanina sought.

Ratio-decidendi:

Conclusion on the main issue 98. For the reasons given, the test applied by the Court of Appeal in determining whether the judge was entitled to set aside his order made at the without notice hearing was wrong in law. The true position is that on an application, such as the husband made here, under FPR rule 18.11 to set aside an order made without notice, the court is required to decide afresh, after hearing argument from both sides, whether the order should be made or not. There is no requirement for a party applying under FPR rule 18.11 to set aside leave to demonstrate a "knock-out blow", or a compelling reason why the court should exercise the power to set aside, or that the court was materially misled. The onus remains on the applicant for leave to satisfy the court that there is substantial ground for the making of an application for financial relief under Part III. It follows that the Court of Appeal was wrong to set aside the order made by Cohen J on 8 November 2019 following the inter partes hearing on the ground that it did’.

Lord Leggatt (the majority Judgment)

‘No fundamental principle of justice, equity or fairness is at stake 139. It is easy to assert that, as a general principle, any procedure which enables one side to obtain relief from the court in the absence of the other, which then imposes a steeper hurdle on the other for getting it set aside is one-sided, unfair and therefore unjust. Audi alteram partem appears to have been infringed. That is no doubt why the usual procedure for the hearing of an application to set aside relief obtained without notice is, in substance, a re-hearing on the merits. But the question whether any particular procedure falls foul of that principle needs to be considered in context. 140. Most forms of relief obtained on a without notice application have an immediate, even if usually temporary, effect upon the absent respondent's rights and liberties. They may be inhibited in dealing with their property by a freezing order. Their premises and records may have been thoroughly searched, and material taken away, by a search and seize order. They may have been prohibited from specified types of conduct, by a without notice injunction. These types of relief are only granted without notice if there is some compelling reason, usually of urgency or effectiveness, which makes it inappropriate to require that the application be made on notice. In all those types of case the court generally grants relief on terms which are designed to ensure that the respondent has the earliest and fullest opportunity to advance any reason why the relief should be discharged on the merits. 141. In the present context the relief sought without notice is only the court's permission to bring the Part III proceedings. That has no immediate effect upon respondents' rights and liberties. They are in the same position as any ordinary respondent or defendant to legal proceedings, the overwhelming majority of which (whether civil or family) do not require the court's permission before they can be commenced. Like other such respondents and defendants, respondents to Part III claims are required by rules of court to undertake various procedural steps, such as giving disclosure, answering questions about relevant matters, setting out their case and generally preparing for trial, at what may be substantial expense of time and money. 142. Furthermore, and in sharp contrast with leave to serve proceedings out of the jurisdiction, the grant of leave to bring Part III proceedings does not foreclose any issue of substance between the parties, regardless whether the leave was granted on an application heard with or without notice. The issues of substance will, in particular, include an assessment of all the matters relevant to the question whether it is appropriate for the English court to make an order at all (the "appropriate venue" question in the heading to section 16). Indeed section 16 makes it clear that this assessment must be conducted by reference to matters as they stand at the time of the final hearing, so that any examination of them at the permission stage must, in a case where leave is then given, necessarily be provisional’.

Lord Briggs (dissenting)

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.