Mueen-Uddin v Secretary of State for the Home Departments [2024] UKSC 21 (20 June 2024)

Citation: Mueen-Uddin v Secretary of State for the Home Departments [2024] UKSC 21 (20 June 2024)

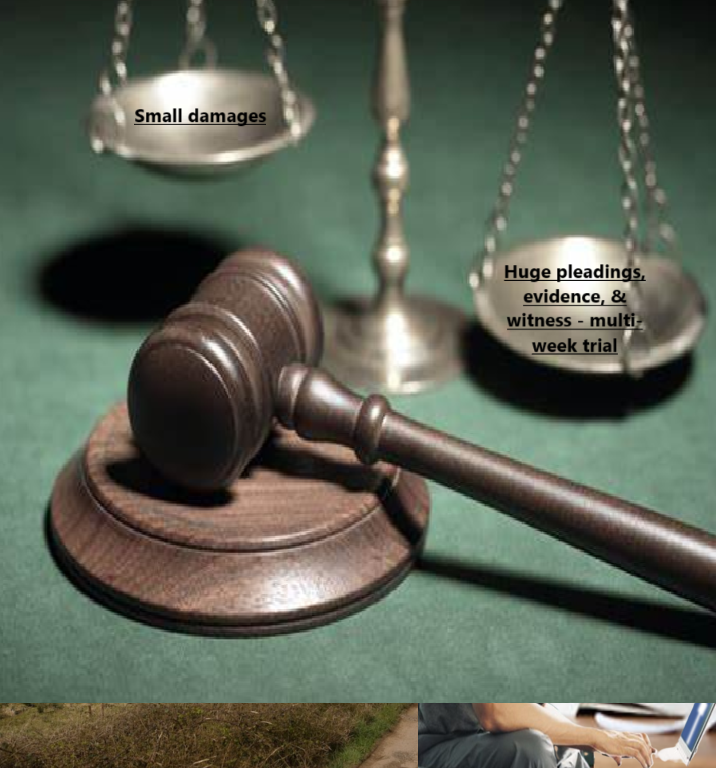

Rule of thumb: What is an abuse of process in terms of the size of the proceedings lodged in the Court? It is prima facie an abuse of process when the cost of litigation massively outweighs the damages – under the modern concept of this the damages do however include potential damages throughout a career, or indeed damages being sustained widely by people in similar scenarios – it is not a simple comparison of damages being sought to legal costs & expenses.

Background facts: This case invoked the subjects of procedural law, Solicitor negligence, and defamation.

The basic facts of this case were that Mr Mudin grew up in Bangladesh – this was at a time when atrocities were perpetrated by the Bangladeshi Government. A Home Office Report was published accusing Mudin of involvement in some way. Mudin denied this & sought to raise defamation proceedings. The Home Office sought to have these allegations struck out as an abuse of process – the damages Mudin suffered as a result were small in comparison to the cost of what a litigation to establish the truth would be.

Court held: The Court held that it was not an abuse of process for this case to be raised. Where an individual’s entire reputation is on the line with allegations against them which are believed to be untrue, then it is not an abuse of process to seek to have this litigated even it would indeed be an extremely expensive litigation.

Ratio-decidendi:

‘A multi-factorial approach? On the facts of a particular case, it is possible that more than one form of abuse of process may be relevant. It is also possible that some of the categories of abuse of process may overlap. The approach adopted by the majority of the Court of Appeal proceeded, however, on a different basis. In relation to Hunter abuse, they concluded that even if the claimant's challenge to his conviction did not constitute such abuse, it could nevertheless contribute, along with other considerations, to the conclusion that the claim was an abuse of process. In relation to Jameel abuse, although their reasoning is less clear, they appear to have treated their finding that the value of the claim was greatly exceeded by the cost of the litigation as a factor which contributed to an overall conclusion that the claim was an abuse of process. The supposed unfairness resulting from the Secretary of State's difficulty in establishing a defence of truth appears to have been treated as another factor in the overall assessment.

This approach was rightly described by Phillips LJ, at para 84, as unprincipled. The Hunter principle and the Jameel principle protect different aspects of the public interest, and have different rationales. Where neither principle is satisfied, the considerations which were relevant to each principle cannot simply be lumped together. If they are considered to be relevant to some other principle, that principle has to be identified and defined.

For the reasons explained earlier, it is not an abuse of process for the claimant to bring a claim which involves a collateral challenge to his conviction by the ICT: on the contrary, it is a proper use of civil procedure. That being so, the fact that the claim involves a collateral challenge to a prior conviction cannot count against the claimant in some wider assessment of whether the proceedings are an abuse of process. Similarly, if the claimant has suffered more than minimal damage to his reputation and so meets the test laid down in Jameel and Lachaux, then the fact (as the majority of the Court of Appeal considered it to be) that the value of the claim is less than the cost of the litigation cannot bear on an overall assessment that the claim is an abuse of process, in the absence, at least, of some other principle of abuse of process, to which that fact is relevant. No such principle has been identified in this case. Furthermore, the reasoning which led the majority of the Court of Appeal to conclude that the claim was of little value was erroneous, as explained at paras 90–115 above. Finally, for the reasons explained at paras 65–71 above, the Secretary of State's difficulties in tracing witnesses and other evidence do not render the claim an abuse of process. Those difficulties simply reflect the fact that the Secretary of State has chosen to make an allegation against the claimant concerning events which occurred more than 50 years ago, and bears the burden of proof in establishing a defence of truth. It is perfectly proper for the claimant to bring these proceedings notwithstanding the Secretary of State's difficulties in establishing a defence of truth. That being so, the Secretary of State's difficulties cannot count against the claimant in some wider assessment of whether the proceedings are an abuse of process’.

At 121-123

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.