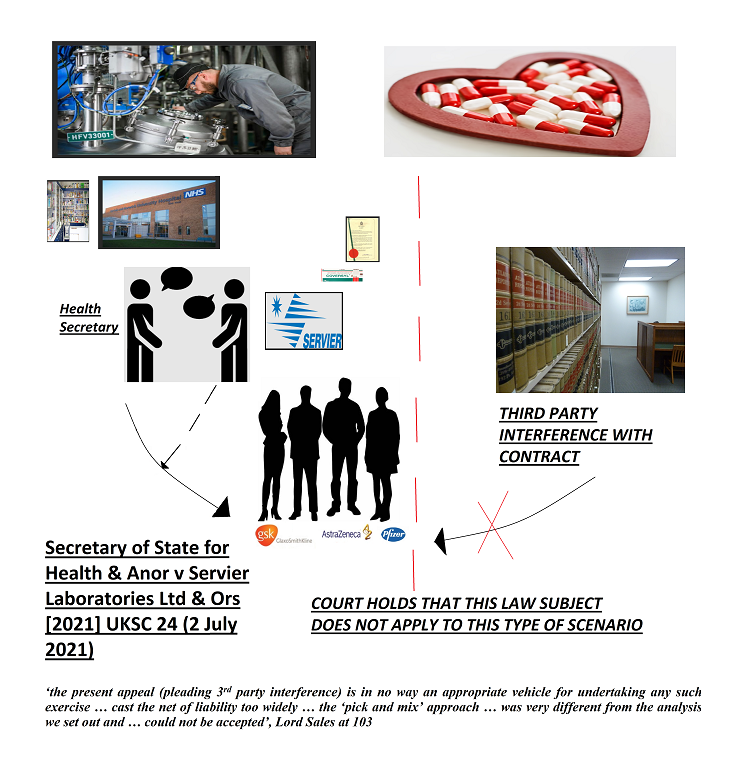

Secretary of State for Health & Anor v Servier Laboratories Ltd & Ors [2021] UKSC 24 (2 July 2021)

Citation:Secretary of State for Health & Anor v Servier Laboratories Ltd & Ors [2021] UKSC 24 (2 July 2021).

Subjects invoked: 12. 'Procedure'.71. 'Interference with contract'.10. 'Jurisprudence'.11. 'Legal methods'.

Rule of thumb:If you explain the facts of your case to the Court & explain how they were unfair, can you expect the Court to research and explain what laws were broken towards you? No, the Court affirmed that even if a case raised by one person against another evokes a sense of injustice, the aggrieved party still has to inform the Court of the right law subject that has been breached towards them. Informing the Court of the law subject breached is the first step in raising the claim - if the aggrieved party does not correctly inform the Court of the correct law subject that has been breached towards them, and none of the cases they present possess even broadly inductive reasoning to support their position, then they cannot raise a successful claim - the Court further explained that where the right subject invoked is not outlined, the case is also procedurally irrelevant.

Background facts:

This case invoked the subjects of jurisprudence, legal methods, procedure and third party interference with contract.

The facts of this case were that Servier were a pharmaceutical company. Servier claimed that they had manufactured a new type of blood pressure drug which they made out was to be more effective than competitors in the treatment of a particular type of high blood pressure/hypertension, and they called this drug ‘Perindopril’. Servier essentially led people to believe that Perinpodril was a new way of treating a particular type of blood pressure which was better than the other generic blood pressure drugs. Servier applied to the European Patent Office with initial data and obtained a ‘preliminary patent’ for Perindopril. They then continued to follow the registration procedures, provided fuller data to the Patent Office, and obtained a full patent certificate for this. The way patent registration procedures work is that even when someone has a full patent certificate, there is still a fairly lengthy period of observation on it afterwards where it can still be withdrawn, and Perinpodril was still in this ‘observation period’.

As time passed, and a large body of data became available from patients who were using Perinpodril, it became abundantly clear that Servier had put in this patent application without proper grounds to do so. The full body of data showed that Perinpodril was clearly just the same as all the other blood pressure drugs on the market at the same. Perinpodril added nothing new to market - Servier had submitted misleading data and information on their application to obtain the patent for Perinpodril. Once the European Patent Office discovered that Servier had misled them about the effectiveness of Perinpodril, they withdrew the patent certificate for Perinpodril. Once this patent certificate withdrawal for Perinpodril occurred, Servier lost their place as the market leader for providing drugs to treat that particular type of high blood pressure.

The UK Secretary of State for Health, who buys the drugs for the NHS, bought Perinpodril from Servier for several years whilst it had the full patent certificate because it was thought to be an innovative drug which was more effective at treating a particular type of high blood pressure. The UK Secretary of State paid higher than the market rate for Perinpodril when they thought this drug was innovative and more effective than the competitor products, rather than just buying the standard blood pressure drugs which were a lot cheaper than Perinpodril but just as effective. Once the UK Secretary of State for Health became aware that Perinpodril had its patent certificate withdrawn because it was no better than any of the other blood pressure tablets, there was a great sense of injustice. The UK Secretary calculated that it spent an extra £200 million buying Perinpodril from Servier rather than just buying the cheaper generic blood pressure tablets, and they wanted this money back from Servier. Servier refused to pay them this and so the matter went to Court.

The Health Minister argued that the law subject of ‘3rd party interference with contract’ applied to this matter. The Minister argued that his department were set to purchase blood pressure drugs from other pharmaceutical companies and extend existing contracts they had with these companies, but Servier then interfered with them to stop them from doing so due to the misleading information about their ‘innovative’ new drug which Servier registered with the Patent Office, leading to the Minister buying this drug instead and spending £200m extra. They argued that this law subject applied to ensure that they were entitled to their £200m back.

Servier argued that the Health Minister’s arguments were irrelevant. They argued that the scope of the ‘3rd party interference with contract’ as a law subject did not extend to cover this type of scenario. Using case law for this subject Servier explained there was no case law to support the Minister, and argued that this subject only fundamentally applied to 2 people who were in currently in a contract and a 3rd party interfered to bring it to an end, or, one party being about to contract with another until a 3rd party interfered - which Servier argued would at best only potentially cover Servier’s competitors rather than the UK Government.

Judgment:

The Court upheld the arguments of Servier. The Court affirmed that even although the UK Government’s interpretation of the words ‘3rd party interference with contracts’, and their explanation of how it applied, did make a degree of sense, the actual legal meaning of these words and the legal scope of the subject did not apply to their scenario. The Court went through the most similar cases in this subject and stated that none of them applied even inductively – the UK Government were looking to over-extend the scope and the case-law of this subject to a level which it just could not extend to. The Court further clarified that the procedural principle of relevancy did apply to this matter. The principle of relevancy means that the other party to the litigation must state a law subject which has allegedly been breached in order for the action to have a chance of success. The Court held that the UK Government’s case against Servier was irrelevant, as it was extremely clear that the subject ‘third party interference with contract’ subject did not apply to the factual scenario of this case as none of the cases were sufficiently close to the case at hand. Servier did not have to pay the £200 million to the UK Government.

Ratio-decidendi:

Lord Sales ratio decidendi at 103, ‘103. What is clear, however, is that … the present appeal is in no way an appropriate vehicle for undertaking any such exercise. The development of the “economic torts” has involved a search for appropriate control mechanisms, lest they get out of hand and cast the net of legal liability too widely. The dealing requirement articulated by Lord Hoffmann in the OBG case was deliberately adopted by him as one control mechanism in relation to the unlawful means tort, as was his holding that to qualify as relevant unlawful means the conduct in question should be independently actionable in civil law. On the other hand, he endorsed a relatively wide concept of intention to harm, drawn from Sorrell v Smith [1925] AC 700. The balance struck by Lord Hoffmann and the majority in the OBG case between these elements was considered and deliberate. If consideration were now to be given to adjusting his approach to the first two elements to relax their limiting effect, it would also require careful consideration of whether that could be compensated by a countervailing adjustment to tighten and narrow the concept of intention. Mr Crow QC for the appellants did not make submissions about this, because on the facts of this case the appellants could only succeed on the basis of a wide, Sorrell v Smith form of intention as an element of the tort. As Ms Demetriou QC rightly responded to Mr Crow’s reference to things said by Professor Davies and me in our article, he adopted a “pick and mix” approach which was very different from the analysis we set out and which could not be accepted’.

‘the present appeal (pleading 3rd party interference) is in no way an appropriate vehicle for undertaking any such exercise … cast the net of liability too widely … the ‘pick and mix’ approach … was very different from the analysis we set out and … could not be accepted’, Lord Sales at 103

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.