T (A Child), Re [2021] UKSC 35 (30 July 2021).

Citation:T (A Child), Re [2021] UKSC 35 (30 July 2021).

Subjects invoked: 39. 'Public services torts'.108. 'Right against degradation'.97. 'Social security'.11. 'Legal methods'.

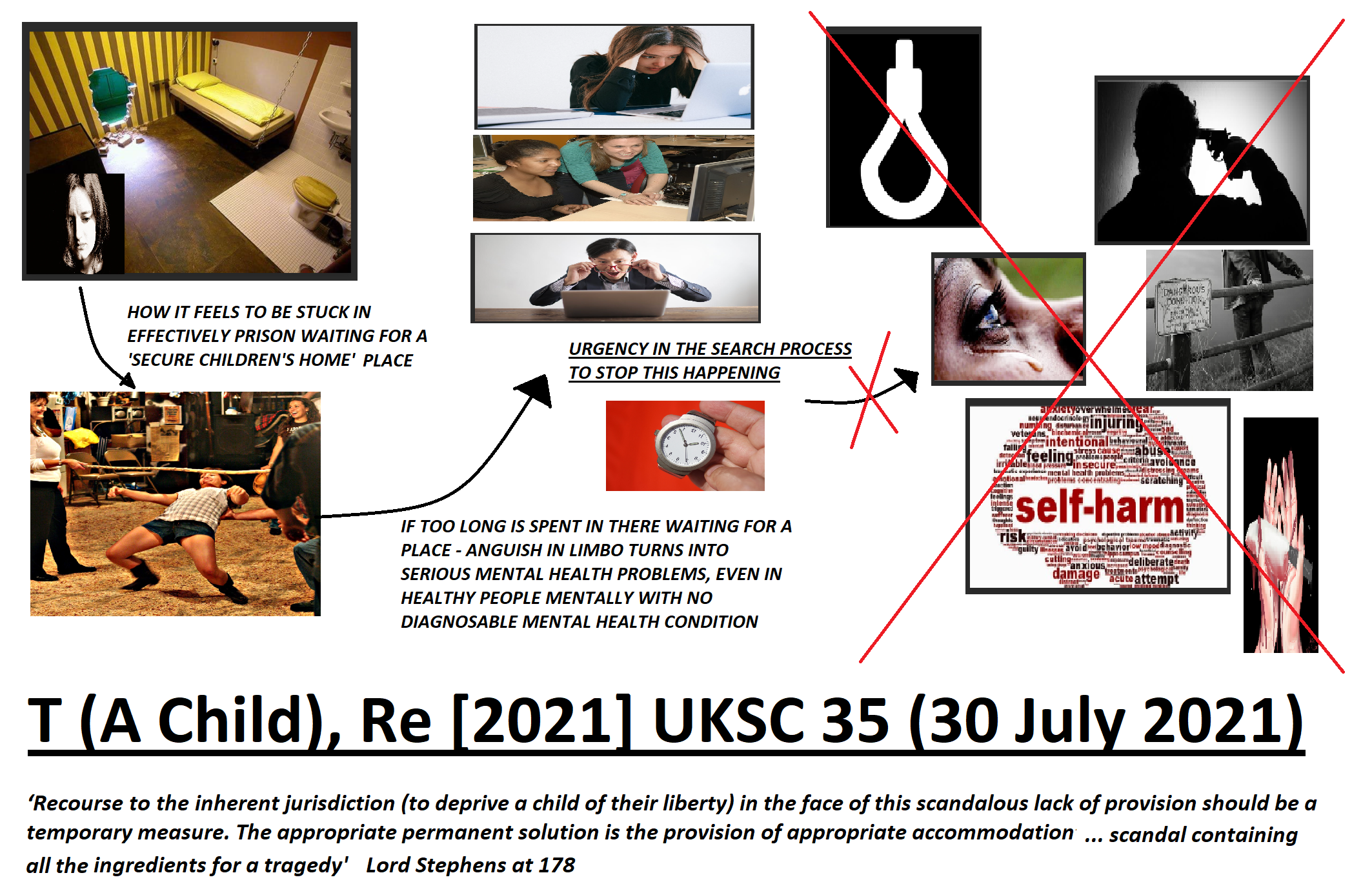

Rule of thumb:When an incontrollable problem child is removed from their parents and put into care, is imprisoning them until an appropriate placement is found a violation of human rights? No, although this should only be done for a short period, or else it becomes a human rights violation. The Court affirmed that the process of essentially imprisoning ‘problem children’, who can no longer live in their previous family home, whilst trying to find an appropriate ‘secure children’s home’ for them, was an urgent situation requiring investment and resources in it to make it work at a quick speed - the Court affirmed that if child was subjected to this imprisonment for longer than a ‘temporary’ period it would be a violation of the rights to life & non-degradation.

Background facts:

This case invoked the subjects of public services delicts/torts, social security law, the human right not to be subject to degrading conditions & the human right to life.

T, essentially a ‘problem child’ who could no longer stay with her parents/guardians, was trying to get a placement in a ‘secure children’s home’ - a secure home for children with problems integrating into society who did not have parents capable of looking after them properly. However, when it was identified that T qualified for a place in one of these secure children’s home, a search for a place was then carried out by the local authority, Caerphilly Council, and it was confirmed that there were no ‘appropriate’ placements for T in a secure children’s home that was near her friends and family at that time. The local authority therefore applied to the Court for T to have a ‘deprivation of liberty order’ imposed on her until an appropriate place in a secure children’s home became available – essentially imprisoning T until a place became available somewhere in other words. T sought to argue that this imprisonment of her, and an increasing number of children like her who also found themselves in the same position of waiting for a placement in a ‘secure children’s home’ after they were unable to keep living in their former family home, was automatically a breach of legislation, including the children’s Act, and a violation of her Article 5 right to liberty. T called for a blanket ban upon this practice of imprisoning children like this.

Before going on to consider whether to uphold T’s arguments, the Court made reference to comments by Judges in cases before them, who essentially said they were extremely unhappy about the growing numbers of these requests for orders to essentially imprison a child waiting for a placement in an appropriate secure children’s home – aghast at the lack of money/resources invested by the Government into this area of the public services. The Court considered the wider picture of how this had affected other children in the past who found themselves in T’s position. The Court referred to the case of G, another young female who was in a similar position to T waiting for a placement in an appropriate secure children’s home. The Court pointed out how T engaged in a spate of self-harming and suicide attempts, as well as other deeply aggressive and violent behaviour. When G was assessed by mental health professionals, it was diagnosed that G had no mental illness however, and that all her problems were environmental, meaning that it was indeed purely the absolutely diabolical living conditions she was faced with which caused her to behave like this, with there being nothing inherently medically wrong with G.

T’s arguments were fundamental and uncompromising. T argued that there should be a blanket ban on Court granting these orders to essentially imprison a child until an appropriate secure children’s home became available. T argued that the Court should declare this practice to be a human rights violation of the Article 5 right to liberty, with all orders for it from local authorities refused, and force the Government to invest more resources into this to prevent this abhorrent practice taking place – it was argued that the imprisonment of children like this was a draconian measure, a repulsive stain on UK society, and must be outright banned.

The local authority argued that this practice was not a human rights violation nor a breach of the various children’s Acts. They argued that whilst there were budget problems, a bigger problem was that it was not easy to find a fairly close secure home for a ‘problem child’ which still allowed them to be near friends & family. They argued that they entered dialogue with children and a lot of them consented to the ‘imprisonment’ regime, rather than be placed in a secure children’s miles from where they grew up, which by and large isolated from their friends and family. They argued that the system perhaps needed more urgency, but did work.

Judgment:

The Court in this case rejected the fundamental arguments of T that the temporary imprisonment of children waiting to find an appropriate secure home was not a violation of their right to liberty. The Court held that the system of children being temporarily placed in this system until a ‘secure home’ which seemed decent to them could be found, particularly if the child sensibly consented to this and were updated about the urgent measures being taken to try to get them a place, was better than them being placed in any old secure home anywhere which did not suit them. The Court did not however fully back the current modus operandi/ status quo.

The Court however emphasised that this should only be a temporary measure, affirming this was an emergency situation requiring urgency and resources invested in it to make work. It affirmed that if any child was subjected to this imprisonment for anything longer than a temporary period, particularly an excessively long period without their consent to this and without communication about the actions being actively taken to find them a place, this would likely be a violation of their Article 2 and Article 3 human rights to life & non-degradation because of the suicide thoughts excessive waiting in this process were shown to ferment in children.

In short, T’s polarised argument technically failed, but a warning was given to local authorities about the investment and urgency needed in this process of finding a suitable ‘secure children’s home’ for ‘problem children’ to prevent it becoming a human rights violation – namely Article 3 the right not to be subject to degrading conditions, and the Article 2 right to life, as there was clear medically supported evidence that healthy children who had no diagnosable mental illness could be driven to serious mental health deterioration, self-harm or indeed suicide if they were subjected to this waiting period for too long.

Ratio-decidendi:

Lady Black ratio-decidendi 160-163 ‘160… this is too simplistic an analysis of the court’s role in an application of this type … there is an important distinction between … determining whether, in any given set of circumstances, someone is deprived of their liberty for article 5… and, on the other hand, making an order … authorising a local authority to restrict a child’s liberty. The former is a factual question... The latter is a prospective order, authorising… a local authority to take steps in response to events... The focus is upon whether or not the factual circumstances justify the restriction… 161… anxious to stress … the importance, for the protection of a child, of the court’s involvement in authorising a deprivation of liberty... This is not the occasion for a comprehensive exploration of the complications attending consent to deprivation of liberty… difficult issues about the pressures that circumstances may place on a child to consent to a proposed arrangement, an apparently balanced and free decision made by a child may be quickly revised and/or reversed… insecure may be the child’s apparent consent. Having said that, there may also be cases in which the child is expressing a carefully considered and firm view. 162. When the court considers the local authority’s application, any consent on the part of the child will form part of the circumstances that it evaluates … The child’s … personal autonomy will be respected by being fully involved in those proceedings, and able to express views about the care … proposed… in a case where the local authority is authorised to deprive the child of his or her liberty but, when it comes to putting the restrictive arrangements into practice, the child is in fact consenting to them in circumstances where that consent is valid and sufficient, there would be no deprivation of liberty… 163. Stepping back from the detail, I would dismiss the appeal… As for the appellant’s principal argument, that is that the inherent jurisdiction cannot be used to authorise a local authority to deprive a child of his or her liberty… I would reject that for the reasons fully set out above… expressions of my deep anxiety that the child care system should find itself struggling to provide for the needs of children without the resources that are required… the inherent jurisdiction is there to fill the gaps in the present provision, but… it is only an imperfect stop gap, and not a long term solution’.

‘178. I agree with Lady Black that recourse to the inherent jurisdiction in the face of this scandalous lack of provision should be a temporary measure (see para 142 above). The appropriate permanent solution is the provision of appropriate accommodation. I add my name to the list of judges who have called attention to this issue which is a scandal containing all the ingredients for a tragedy’, Lord Stephens Ratio-Decidendi at 178

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.