Tinkler v Revenue and Customs [2021] UKSC 39 (30 July 2021)

Citation:Tinkler v Revenue and Customs [2021] UKSC 39 (30 July 2021).

Subjects invoked: 12. 'Procedure'.80. 'Taxation - general/income'.

Rule of thumb:If a litigant does not send an intimation of claim letter to the correct address, is it a valid intimation letter? No, however, if the other litignt obtains it anyway and replies, then the fact it was sent to the wrong address is irrelevant.

Background facts:

This case invoked the subjects of tax and procedural law.

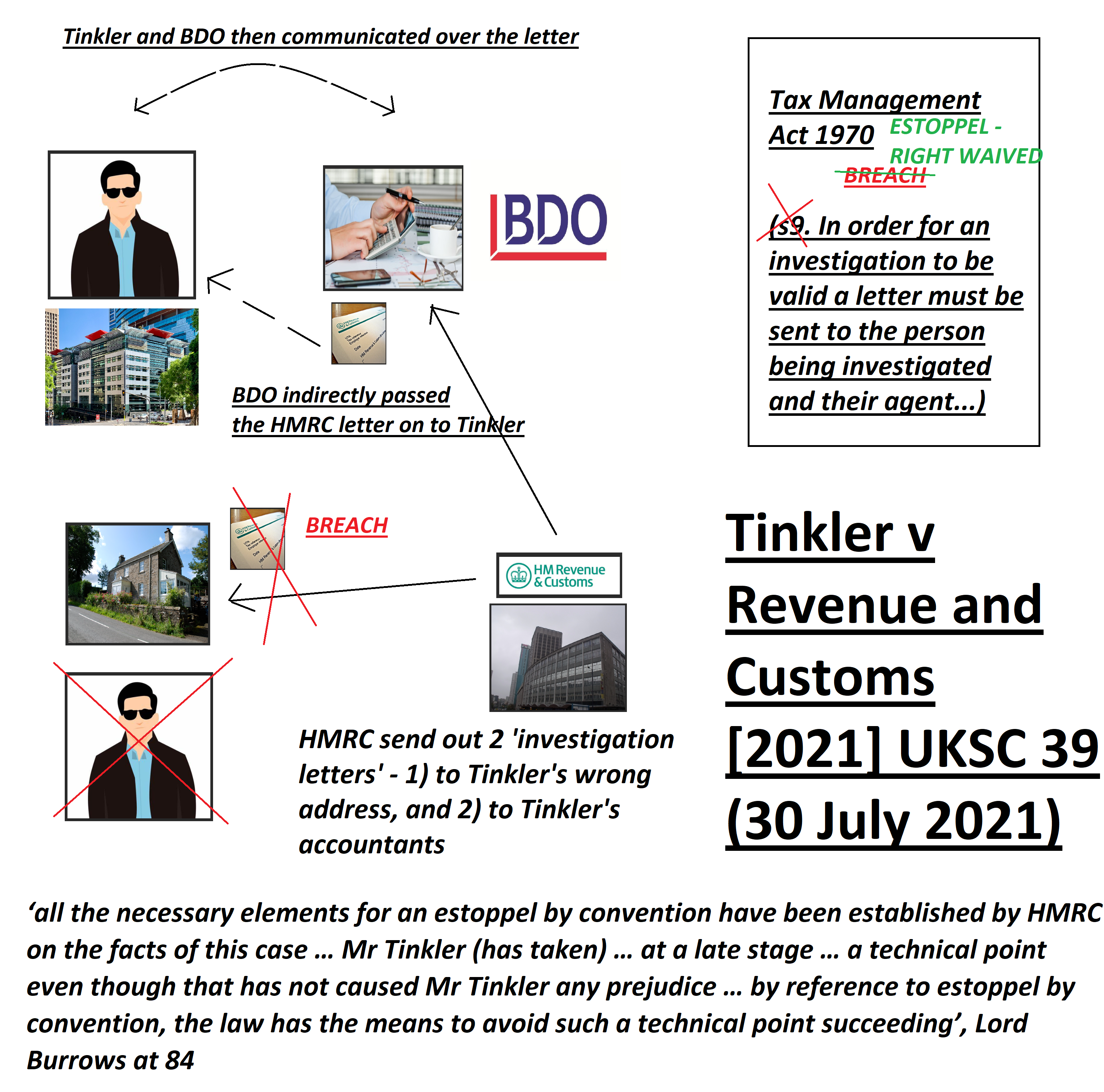

The facts of this case were that in pre 2005 Tinkler was living in rented accommodation in ‘Heybridge Lane’, and HMRC had this as Tinkler’s correspondence address. In or around January Tinkler moved out of this address and so updated his address with HMRC to his business address ‘Station Road’. On 31st of January 2005 Tinkler provided a self-assessment tax return to HMRC, which even had his new address on it as well. On 15th of March 2005 Tinkler then provided a tax return to HMRC paying them £700k.

In June 2005 HMRC decided to investigate Tinkler over his tax return. On 1st of July 2005 HMRC wrote to BDO, Tinkler’s accountants, informing them of this investigation. On the 1st of July 2005 they also sent this letter to Mr Tinkler’s ‘Heybridge Lane address’. BDO acknowledged this investigation on the 6th of July 2005. However, Mr Tinkler never received this letter because it was mistakenly sent to his old incorrect ‘Heybridge Lane’ address, rather than his new ‘Station Road’ address.BDO tried to defend this, and in November 2005, Tinkler provided BDO with information to try to help them stave off this investigation. In August 2012, HMRC finally confirmed to Tinkler that their investigation into the matter was over. They stated that it was their belief that Tinkler had underpaid in his tax, and he either had to pay up what they believed he owed, or the matter was being taken to the Tribunal. Tinkler then argued that HMRC were not legally entitled to do this as they had sent their original intimation letter to the his wrong correspondence address, and the whole investigation process had to be started again (or the case was maybe time-barred).

Tinkler argued that the principle of interpretation of statute applied in this matter. Tinkler argued that s9 of the Taxes Management Act 1970 stated that in order for a tax investigation to be validly initiated the intimation letter affirming that HMRC were investigating a person had to be sent to the correct address of the person being investigated, and also the address of the person’s representatives. Tinkler argued that HMRC made the mistake of sending this intimation letter to his old address, the wrong one, rather than the new one he provided them with, and this meant their whole investigation was in breach of statute & invalid. HMRC argued estoppel applied. HMRC argued that estoppel means that statutory breaches can be waived by one of the parties and agreed not to be relied upon – they argued this administrative error in breach of statute was waived by Tinkler and under principle of estoppel he could not then change his mind later and then argue it did apply later on. HMRC argued that because both Tinkler and his representatives had engaged in negotiations over the unpaid tax despite them sending it to the wrong address, they had negotiated/fought the matter anyway, meaning they waived HMRC’s mistake and under estoppel it could not then be argued later.

Judgment:

The Court upheld the arguments of HMRC. It affirmed that even although HMRC had breached the statutory requirements of how to properly initiate the tax investigation, by Tinkler nonetheless continuing to correspond, negotiate and fight the case with HMRC over this anyway, rather than ignore all correspondence, by the principle of estoppel, Tinkler had agreed that this statutory procedural requirement was waived and not being relied upon. The HMRC investigation was deemed to be valid and over, and Tinkler was not entitled to another period of investigation before a Tribunal case was raised, or indeed argue HMRC’s case against him was time-barred.

Ratio-decidendi:

Lord Burrows Ratio-Decidendi 84-85 ‘84. In my view, the appeal should be allowed because all the necessary elements for an estoppel by convention have been established by HMRC on the facts of this case. The five Benchdollar principles, subject to the Blindley Heath amendment to the first principle, comprise a correct statement of the law on estoppel by convention in relation to non-contractual dealings (and, although not necessary to decide this, in relation to contractual dealings). I have sought to explain the ideas underpinning the first three Benchdollar principles which may provide assistance in the understanding and application of those principles. On the facts of this case, the five principles are all satisfied. Moreover, contrary to Mr Thomas’s additional two submissions, the mutual dealings of the parties fall within the scope of estoppel by convention and there is no statutory bar. BDO/Mr Tinkler are therefore estopped from denying that a valid enquiry was opened by HMRC. 85. Standing back from the detail, what Mr Tinkler and his advisers have done is to take at a late stage what can fairly be described, on the facts of this case, as a technical point (that the notice of enquiry was sent to the wrong address) even though that has not caused Mr Tinkler any prejudice. It is entirely satisfactory that, by reference to estoppel by convention, the law has the means to avoid such a technical point succeeding’.

‘all the necessary elements for an estoppel by convention have been established by HMRC on the facts of this case … Mr Tinkler (has taken) … at a late stage … a technical point even though that has not caused Mr Tinkler any prejudice … by reference to estoppel by convention, the law has the means to avoid such a technical point succeeding’, Lord Burrows at 84

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.