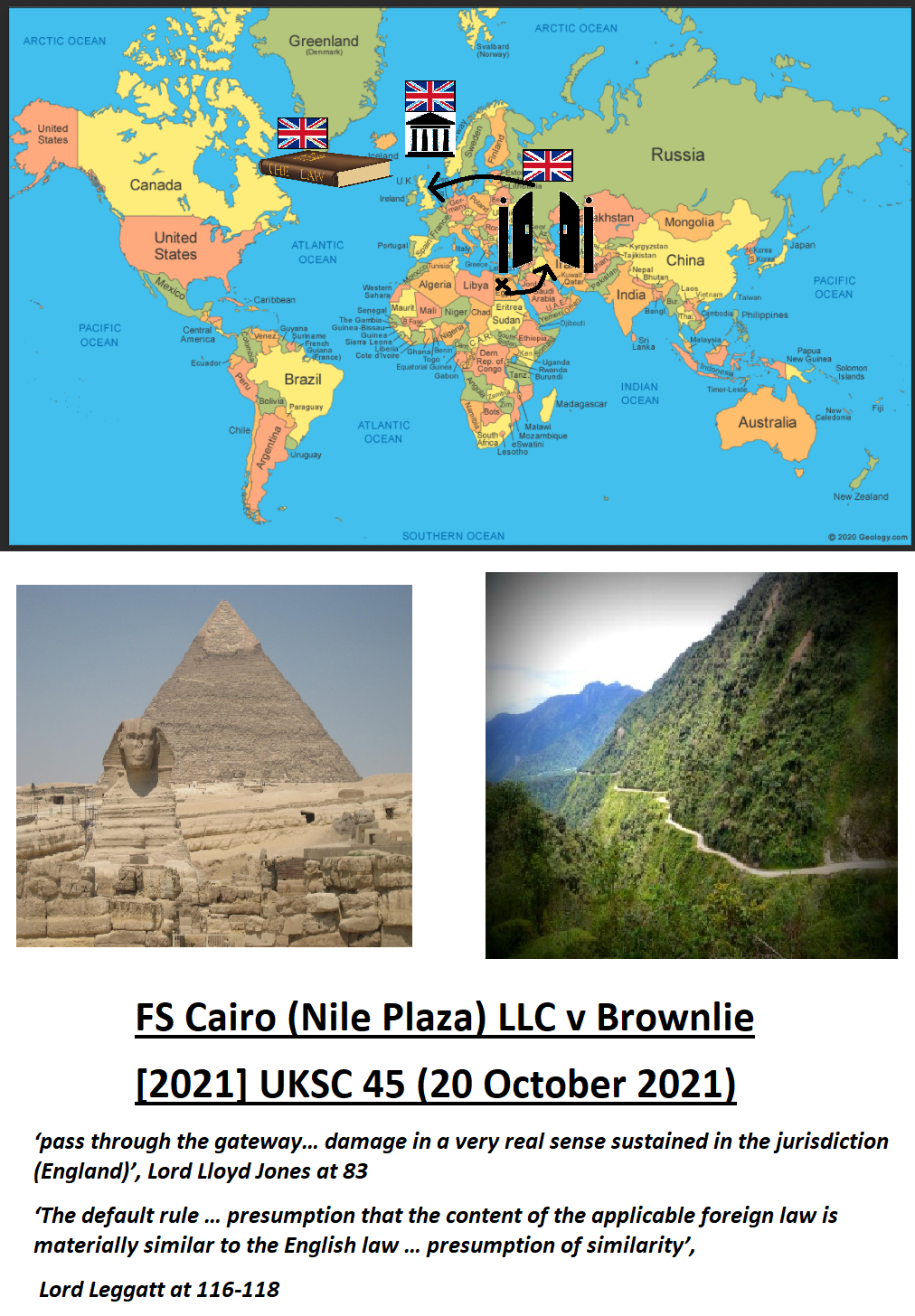

FS Cairo (Nile Plaza) LLC v Brownlie [2021] UKSC 45 (20 October 2021)

Citation:FS Cairo (Nile Plaza) LLC v Brownlie [2021] UKSC 45 (20 October 2021).

Subjects invoked: 1. 'Nation'.12. 'Procedure'.80. 'Road traffic accident'.

Rule of thumb:If you are injured abroad, can you have the personal injury trial in the UK? Is it UK law or foreign law that applies? The answer to the 1st question is, yes, and the answer to the 2nd question is yes until shown otherwise. This case upheld 3 points of law about when and how a person who believes they have suffered a breach of the law whilst a foreigner abroad, can raise the claim in the UK Courts once they are back home against the alleged perpetrator of the breach. Point of law 1 – the ‘gateway principle’ – there are only a certain number of types of claim that are deemed to be ‘gateway claims’, which people are allowed to raise in the Courts of their home country, rather than the Courts of the foreign country where the alleged breach of the law took place. Not every type of claim is a ‘gateway’ claim that can be raised outside of the country where the alleged breach took place. Point of law 2 – the ‘equivalency/comity principle’ – this means that if the pursuer/plaintiff shows how UK law was breached when they were abroad, then on the basis of the international law principle of legal comity this is presumed and deemed to apply to the situation at hand to prove a legal breach. This applies until and unless the defender/respondent can show that the national law in the foreign country was different from the law in the UK. Point of law 3 – the reasonable prospect of success principle – this means it is not just the normal standard ‘relevancy’ that allows a person to take the case they have raised to trial, in which a person does not need a high odds of success to pursue (A relevancy case can have a low odds percentage prospect of success and still be allowed to run all the way to trial). A case actually has to be strong with a good percentage chance/odds of winning before it is allowed to proceed to a full trial.

Background facts:

This case was in the subjects of international law and procedural law.

The facts of this case were that Lady Brownlie was on holiday with her husband, Sir Ian Brownlie QC, Sir Ian’s daughter, and her own 2 children. They went to a hotel in Egypt at a hotel operated by the Canadian company FS Cairo LLP. The hotel booked a bus for them to go out on day-trip. The driver of this bus crashed, and was subsequently convicted for involuntary manslaughter in the Egyptian criminal Courts. Tragically, Sir Ian was killed in this crash and so was his daughter, Rebecca. Lady Brownlie and her 2 children survived but sustained very bad injuries. Lady Brownlie brought a personal injury claim against FS Cairo for the injuries she sustained and for loss of society in the UK Courts with her claim based upon UK law. FS Cairo opposed this claim on a number of procedural grounds, rather than defend the merits of the driver’s actual actions on the day of the crash.

FS Cairo did not seek to defend the actions of the driver who crashed the bus, but made 3 basic arguments based on procedural law. Firstly, they argued that the UK Courts did not have jurisdiction to hear this case. They argued firstly that tort/delict was not a ground which could be raised in a foreign jurisdiction. They argued that the matter should be raised in the Egyptian Courts. They argued that the English Courts did not have a sufficient connection for the gateway principle to apply. Secondly, FS Cairo argued that Brownlie had made arguments to them about UK/English law which had been breached on the bus. They argued that this case made was irrelevant – they argued that it was Egyptian law which applied and they had no arguments made based upon Egyptian law. Thirdly, they argued that the lowest standard for raising a case against someone in a foreign jurisdiction was higher than just ‘relevancy’. They argued that the test was ‘reasonable prospect of success’ which means a significant percentage around the 50% chance rate. They argued that if Brownlie had not even presented any Egyptian law to make her case then the test of a reasonable prospect of success was clearly not met.

Brownlie pretty much just responded to each of the 3 arguments made by FS Cairo and explained why none of them were of any merit. Firstly, Brownlie argued that the ‘gateway’ principle applied to this matter, which meant that certain claims sustained abroad were able to be applied out of the jurisdiction they took place, namely back in the person’s home country. Brownlie argued that ‘torts’ the nature of which she suffered abroad were one of the ‘gateway’ cases which could be raised as she by and large had sustained all their damages (pain and suffering) in England, thereby giving England a sufficient connection. Secondly, Brownlie also argued that the principle of equivalency and comity applied in her case. She argued that it is presumed that the law is the same in every country, and it will be presumed to be the same until shown otherwise, and her presentation of the UK laws breached applied until the other side were able to show how Egyptian law was different. Bronwlie therefore argued that if what the driver did was not a breach of Egyptian law, which it clearly seemed to be given that he had already been convicted, then it was up to FS Cairo to submit this to the Court and not her. Thirdly, Brownlie argued that as the principle of equivalency allowed her to make UK law arguments, and these UK law arguments made it close to an absolute 100% certainty that she would successfully make a case for a breach of the law, her arguments went well beyond meeting the reasonable prospect of success test needed to make a case against someone outside of their home country. She argued that FS Cairo LLP were not able to make any legal arguments from Egyptian to suggest that the driver’s actions were not a breach of Egyptian law, so at that time the case had a reasonable prospect of success.

Judgment:

The Court upheld the arguments of Brownlie on all 3 points. The Court affirmed that the ‘gateway’ principled applied to delicts/torts sustained abroad of the nature Browlie suffered, and this was a claim which could be raised outside the national jurisdiction where the incident actually occurred. The Court further affirmed that as the damages were suffered in England, ie all the solatium (pain and suffering) was actually felt in England, this gave the English jurisdiction a strong link to the case, and England was therefore an appropriate jurisdiction to hear the case.

The Court also affirmed that Egyptian law did apply to this dispute, however, so did the principle of equivalency, and Brownlie was therefore right to argue that UK/English law applied to it until FS Cairo showed otherwise. The Court therefore held that the UK road traffic laws submitted were sufficient for Brownlie to prove the breaches of the law, and this remained until FS Cairo were able to submit laws from Egypt to suggest that what the driver did was not a breach of the law or not actionable. The Court affirmed that as the UK laws submitted were relevant in absence of the other side presenting Egyptian law to contradict, these laws submitted did give the case a reasonable prospect of success. The case was allowed to proceed to a full trial in the jurisdiction of England and Wales. There was no affirmative Judgement on whether Brownlie was entitled to damages, or what amount of damages she should be entitled to, but these procedural points of law were affirmed in Brownlie’s favour in this matter. (This essentially made it seem extremely likely that FS Cairo would make an offer of damages to Bronwlie to settle the matter, which was of course good).

Ratio-decidendi:

‘pass through the gateway… damage in a very real sense sustained in the jurisdiction (England)’, Lord Lloyd Jones at 83

‘The default rule … presumption that the content of the applicable foreign law is materially similar to the English law … presumption of similarity’, Lord Leggatt at 116-118

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.