Kabab-Ji SAL (Lebanon) v Kout Food Group (Kuwait) [2021] UKSC 48 (26 October 2021)

Citation:Kabab-Ji SAL (Lebanon) v Kout Food Group (Kuwait) [2021] UKSC 48 (26 October 2021).

Subjects invoked: 15. 'contract'.7. 'Company'.12. 'Procedure'.64. 'Trademark'.

Rule of thumb:Can 2 foreign companies operating outside of the UK agree for the UK Courts & UK law to regulate the commercial contract? 2 foreign companies who do not even operate in the UK can agree for UK law to regulate their agreement. If they also state that any disputes have to be raised in the UK Courts, then this is a valid term as well. If the foreign countries’ law-makers formally recognise the UK Courts, then the UK Courts can also make declarations and orders against the foreign parties in the case. UK commercial law could be used as the commercial law for the whole world. The UK Courts will also not deem that a transfer of rights and obligations between a holding company and their subsidiary, an assignation/novation, will have taken place unless this is expressly put in writing.

Background facts:

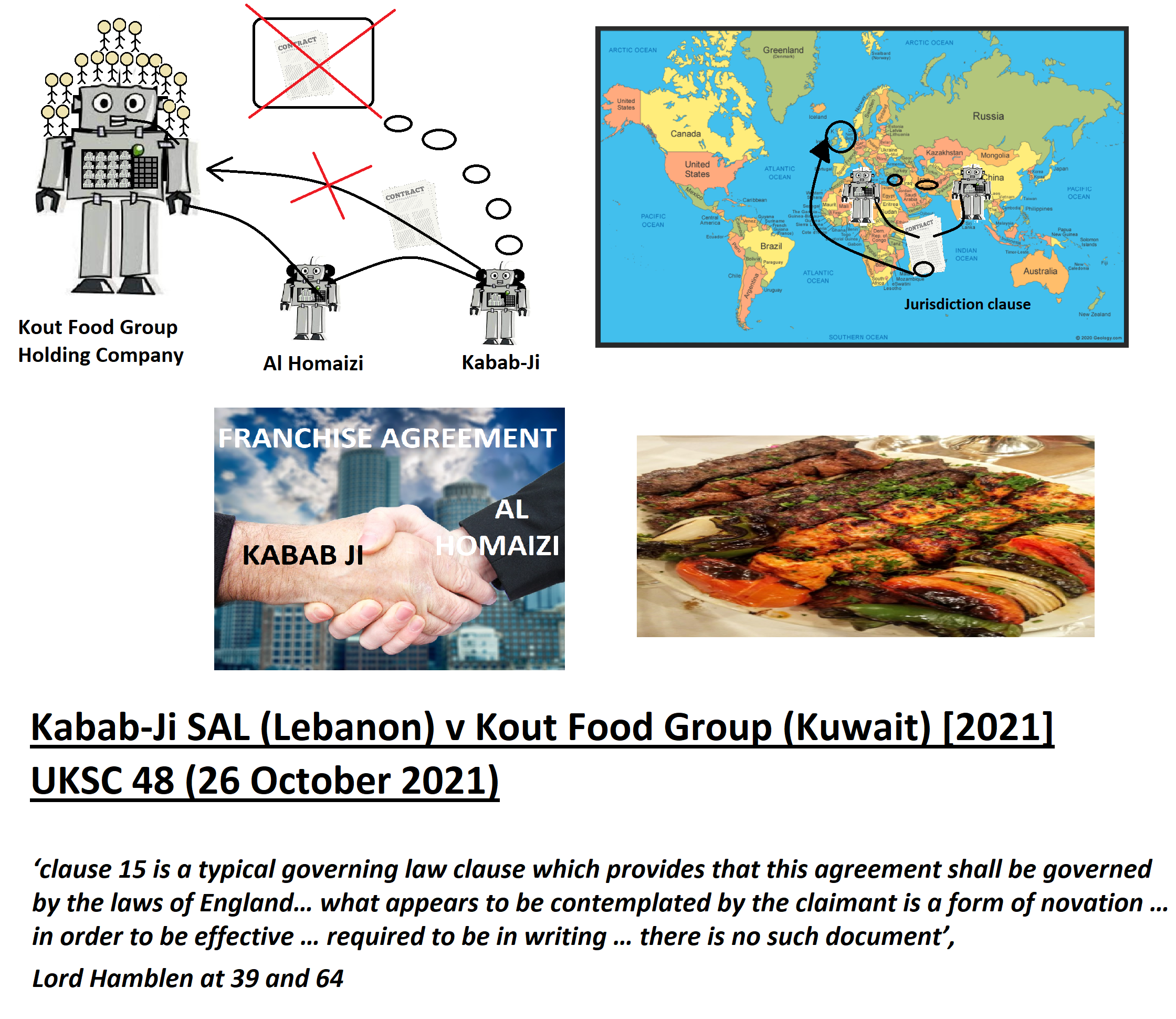

The facts of this case were that Kabab-Ji, a Lebanese company, who specialised in the production of exquisite Lebanese cuisine (high quality Lebanese kebabs and other Lebanese dishes), and had an excellent brand reputation, entered into a franchise contract with Al Homaizi, a Kuwaiti company who were restaurateurs. This franchise agreement was that Kabab-Ji would give Al Homaizi the right to use its trade mark, business processes, recipes and products, so that Al Homaizi could open a Lebanese cuisine restaurant in Kuwait for 10 years selling Kabab-Ji’s much-enjoyed and reputable Lebanese food. There were 3 important clauses in this license contract. Firstly, an arbitration clause. This arbitration clause stated that if there were any disputes then the matter would go to an Arbitration organisation based in France. Secondly, there was a jurisdiction/law governing clause stating that English/UK law would be the applicable standard of commercial law to regulate the agreement. Thirdly, there was a ‘no oral modifications clause’, stating that any time parties did things not in line with the contract this was an exception which did not become a term of the contract – customs/favours did not become terms of the contract in other words.

Al Homaizi was a subsidiary of a larger food and drink group called ‘Kout Food Group’, KFG, another Kuwaiti company. KFG provided holding company services for Al Homaizi and many of their other subsidiaries, which included advice in some contract negotiation processes. As well as providing general holding company services, KFG also manufactured food as a separate branch of their business which they sold to many of their subsidiaries.

Al Homaizi and Kabab-Ji got into a dispute over the license agreement. Kabab-Ji argued that breaches of the license agreement by Al Homaiz had caused £6.7m of damages. They were unable to resolve their differences, and arbitration was needed. Kabab-Ji did not take Al Homaizi, the restaurant they contracted with, to arbitration to resolve the dispute however. They instead sued Al Homaizi’s holding company Kout Group, who were much better financed, and the matter went to arbitration in France. Kout Group underwent the arbitration ‘under protest’ stating that they were not liable for Al Homaizi who was a separate person. The French Arbitration held that due to the fact Kout Food Group helped Al Homaizi negotiate some of their contracts, the French law principle of ‘novation’ ensured that Kout Food Group became a party to the contract with Kabab-Ji, and therefore had to pay the damages under it. Kout strongly disagreed with this & still refused to pay the money the French arbitration stated they owed Kabab Ji. Kout sought to have the matter litigated formally in the English/UK Court system. In short, Kout Food Group, a holding company, owned the shares in the company Al Homaizi, a restaurant business. Al Homaizi had a franchise agreement with Kabab-Ji to become one of their kebab restaurant chains, but Al Homaizi breached this agreement causing Kabab-Ji 6.7m in damages. Kabab-Ji then tried to sue the holding company, Kout Group, rather than Al Homaizi, but this raised a legal dispute between Kout and Kabab-Ji.

Kabab-Ji argued that it was the law of the arbitration clause which regulated the agreement, meaning it was French law rather than English/UK law that regulated the agreement. They argued that under the principle of ‘novation’/assignation in French contract law, which is very flexible, when Kout Group started helping their subsidiary Al Homaizi to some extent in their dealings with Kabab Ji, then a novation took place, and Kabab Ji’s contract became with Kout Group instead of Al Homaizi. In other words, when Kout Group took an interest in this, a novation took place and they replaced Al Homaizi in the contract with Kabab Ji. Kout Group argued first and foremost that them and Al Homaizi were two ‘separate companies’ and two separate people/legal personalities. They affirmed they were the holding company of Al Homaizi, but stated that they had not interfered beyond their remit and beyond their basic duties as a holding company. They affirmed the general fundamental principle that holding companies were not generally liable for their subsidiary, unless there were exceptionally close circumstances between the 2, which there were not in this case. Kout Group then made arguments about the contractual principles invoked under the dispute and went through clauses/terms in the contract. They firstly argued that it was the ‘law governance clause’ and not the ‘arbitration clause’ which determined the law that regulated the agreement. They argued that this meant it was English/UK law governing the agreement, rather than French law. The arbitrators in France should have been applying English/UK law to the dispute rather than French law. Kout Group further argued that no novation/assignation took place under English/UK law, which has a stricter principle of novation/assignation than French law. They argued that under English/UK law in order for a novation/assignation to take place, this must be done in writing to be valid because it is such a fundamental change to the original agreement, and this never happened. Moreover, they stated that there was a ‘no oral modifications clause’, meaning that any oral changes to the contract were not allowed anyway. Kout Group argued that it was clear that by the law of contract in England/the UK they were not liable for their subsidiary’s £6.7 million damages bill.

Judgment:

The Court upheld the arguments of Kout Food Group, the holding company. They held that the ‘law governance’ clause did indeed apply to ensure it was English/UK law regulating the agreement, and not French law. It affirmed that it is possible for any two companies anywhere in the world to enter a commercial agreement, and then use a ‘law governance’ clause to choose which country’s laws they wish to regulate their commercial agreement. They affirmed that the fact that the arbitration was to be held in France did not change this, and the French arbitrators should have applied English/UK law to resolve the dispute during arbitration. The Court secondly affirmed that novation/assignation does require writing in order to be valid under English/UK law. In English/UK two parties can initially form an oral contract, however, if a novation/assignation is to take place, meaning that one of the 2 parties in the contract is being replaced then this must be done in writing in order to be valid. They further argued that where there is a ‘no oral modifications’ clause, there is almost no chance of a novation/assignation being deemed to have taken place orally between Kout and Al Homaizi. In short, Kout Group were not liable for the damages of 6.7 million pounds their subsidiary had caused by breaching their license agreement with Kabab Ji. This case therefore broadly invoked 2 principles in the subject of contract law – ‘law governing clauses’ & ‘novation’/assignation. Firstly, ‘law governing clauses’. The Court affirmed that the law regulating a commercial agreement between 2 parties is the place stated/chosen in the ‘governing clause’ – this is the most important point in determining this. The law in the location the offer and acceptance took place, the law of the location where the contract was to be carried out, or the law in the location where arbitration was to take place, are irrelevant in determining the law that regulates the parties’ commercial relationship where there is a ‘governing clause’. Secondly, the principle of novation/assignation. Novation/assignation is where the rights and obligations in a contract are transferred by one of the original parties to it to another new 3rd party. The Court held that under UK/English law, due to novation altering the most basic fundamentals of the original contractual agreement, it can only generally be done where the new 3rd party to the contract agrees this in writing, not orally. The Court further held that where this lack of a written contract is also supplemented by a ‘no oral modifications clause’ in the original contract, then most certainly no novation will be deemed to have taken place.

Ratio-decidendi:

Lord Hamblen – Ratio Decidendi at 39, 62-65, 75 & 93, 39. In our view, the effect of these clauses is absolutely clear. Clause 15 of the FDA is a typical governing law clause, which provides that “this Agreement” shall be governed by the laws of England. Even without any express definition, that phrase is ordinarily and reasonably understood … to denote all the clauses incorporated in the contractual document… The “law to which the parties subjected” the arbitration agreement in clause 14 is therefore English law… 62-65. The claimant’s main case in the arbitration was that there had been a novation of the FDA by reason of the parties’ conduct and the performance by KFG over a sustained period of time of various obligations under the FDA &… FOAs. In light of… of Al Homaizi’s continued involvement in various contractual matters, at a late stage of the arbitration the case became one of “novation by addition”. This case was accepted by the majority of the arbitral tribunal… Precisely what is meant by “novation by addition”, how and when it came about and the precise terms of the new agreement are not explained by … arbitrators… What appears to be contemplated by the claimant is a form of novation whereby the original contract between the claimant and Al Homaizi was terminated by agreement and replaced by an agreement on the same terms save that the licensee was to be both Al Homaizi and KFG… It follows that, in order to be effective, any such termination was required to be in writing and signed by or on behalf of the claimant and Al Homaizi. There is no such document… There is no signed written document by which the necessary consent is provided. Without such written consent … ineffective…75. … as a matter of English law there was no real prospect that a court might find at a further hearing that KFG became a party to the arbitration agreement in the FDA. Given the terms of the No Oral Modification clauses, the evidential burden was on the claimant to show a sufficiently arguable case that KFG had become a party to the FDA and hence to the arbitration agreement in compliance with the requirements set out in those clauses, or that KFG was estopped or otherwise precluded from relying on the failure to comply with those requirements…93. The law governing the validity of the arbitration agreement is English law. As a matter of English law, the Court of Appeal was right to conclude that there is no real prospect that a court might find at a further evidentiary hearing that KFG became a party to the arbitration agreement in the FDA… It follows that the appeal must be dismissed’. ‘clause 15 is a typical governing law clause which provides that this agreement shall be governed by the laws of England… what appears to be contemplated by the claimant is a form of novation … in order to be effective … required to be in writing … there is no such document’, Lord Hamblen at 39 and 64, 20

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.