REFERENCES (Bills) by the Attorney General and the Advocate General for Scotland - United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and European Charter of Local Self-Government (Incorporation) (Scotland) [2021] UKSC 42 (06 October 2021)

Citation:REFERENCES (Bills) by the Attorney General and the Advocate General for Scotland - United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and European Charter of Local Self-Government (Incorporation) (Scotland) [2021] UKSC 42 (06 October 2021).

Subjects invoked: 10. 'Jurisprudence'.73. 'Executive'.

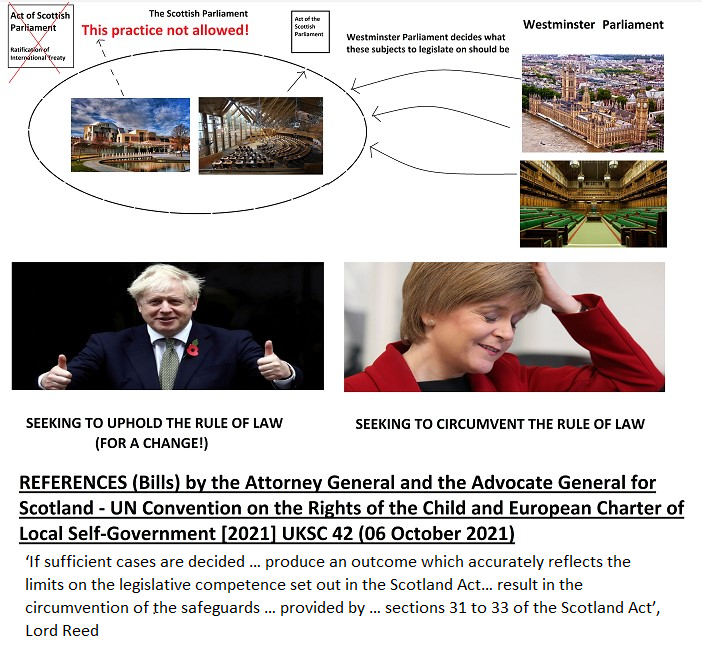

Rule of thumb:Are ratified Treaties a source of primary law or secondary law? Can the devolved legislatures in the UK ratify Treaties in non-devolved areas? The Court first and foremost affirmed that if an international treaty is ratified in Parliament, then it becomes a primary source of law providing broad rights people can directly rely upon as the foundation of an inductive legal argument to obtain remedies in Court, which can eventually lead to case-law giving very strong substantive legal rights to be relied on deductively. The Court also affirmed that the Scottish Government were not allowed to ratify treaties giving rights in non-devolved subjects which the Scottish Parliament did not have legislative competence for.

Background facts:

This case invoked the subjects of Executive/Government and Jurisprudence.

The facts of this case were straightforward. The Scottish Government presented a bill to the Scottish Parliament to ratify in full the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child 1989 & the European Charter of Local Self-Government 1985. Before this Bill could pass through the Scottish Parliament in full to become an Act however, the Attorney General, the legal advisor in the UK Government, informed the Scottish Government that they were not allowed to do this legally as it invoked non-devolved subjects. The Advocate General for Scotland, the Scottish Government’s legal advisor, stated that they were, so the matter went to Court.

To understand this argument the concept of ‘devolved subjects’ has to be understood. The Westminster Parliament is the sovereign Parliament of the country of Great Britain & Northern Ireland, and the Scottish Parliament is not – the Scottish Parliament is essentially a ‘creature of statute’ and effectively just like a quango when it comes down to it. Under the Scotland Act 1998, the Scottish Government and the Scottish Parliament are therefore only strictly allowed to introduce legislation in certain specified subjects which the UK Westminster Parliament has granted them permission to, and they are not allowed to legislate on other subjects.

The Attorney General, the chief legal advisor in the UK Government, argued that these particular Treaties being proposed to be ratified in the Scottish Parliament gave broad rights to people in Scotland which were about non-devolved subjects out-with the legislative competence of the Scottish Parliament. The Attorney General therefore argued that the Scottish Government were most certainly not allowed to ratify these particular treaties because they were giving substantive rights to people in areas which the Scottish Government & Scottish Parliament were not allowed to give.

The Advocate General for Scotland, chief legal advisor in the Scottish Government, argued that the Scottish Government and Scottish Parliament were not actually giving any direct rights by ratifying these treaties. They argued that ratified treaties were so general, vague and unclear that they were only a secondary source of law, and had more symbolic value legally than actual substantive value. They argued that they were not actually giving any direct rights with these treaties which could be relied on by citizens in any legal arguments in reality, meaning therefore that they were not actually introducing right in non-devolved subjects.

Judgment:

The Court upheld the argument of the Attorney General that the Scottish Government could not implement these particular treaties because it would grant people in Scotland legal rights which the Scottish Parliament did not have competence to create rights on. The Court affirmed that a ratified treaty is a source of primary law which provides broad direct rights that people can inductively rely on to make substantive arguments in Court, and with sufficient cases interpreting them can give people deductive rights. The Court held that the Scottish Government could not be allowed to implement these Treaties as they were on non-devolved subjects. The rest of the Judgment was largely a technical exercise going through which parts of these Treaties proposed by the Scottish Government to the Scottish Parliament were non-devolved rights which they could not introduce, and approving the other rights in the Treaties as within the legislative competence of the Scottish Parliament.

Ratio-decidendi:

Lord Reed, Ratio-Decidendi at 79-80 ‘79. The same conclusion must be reached in the present case. Section 101(2) cannot have been intended to enable the courts to undertake, in substance, a rewriting of provisions enacted by the Scottish Parliament, which on their face are plainly and unambiguously outside its legislative competence, so as eventually, if sufficient cases are decided, to produce an outcome which accurately reflects the limits on legislative competence set out in the Scotland Act. That would give section 101(2) a function going beyond interpretation as ordinarily understood. As the “Named Persons” case illustrates, such an approach to section 101(2) would also be liable to contravene key provisions of the ECHR in cases where they were relevant. As I have explained, it would also result in the circumvention of the safeguards intended to be provided by sections 31 to 33 of the Scotland Act, whose operation is dependent on legislative provisions being drafted with sufficient clarity to enable the requisite assessments to be made. 80. For all the foregoing reasons, the answer to question 4 is “Yes”. Section 6 of the Bill is outside the legislative competence of the Scottish Parliament, because it “relates to” reserved matters, contrary to section 29(2)(b) of the Scotland Act, would modify section 28(7), contrary to section 29(2)(c), and would modify the law on reserved matters, contrary to section 29(2)(c)’.

‘If sufficient cases are decided … produce an outcome which accurately reflects the limits on the legislative competence set out in the Scotland Act… result in the circumvention of the safeguards … provided by … sections 31 to 33 of the Scotland Act’, Lord Reed

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.