Alize 1954 & Anor v Allianz Elementar Versicherungs AG & Ors [2021] UKSC 51 (10 November 2021)

Citation:Alize 1954 & Anor v Allianz Elementar Versicherungs AG & Ors [2021] UKSC 51 (10 November 2021).

Subjects invoked: 59. 'Shipping'.

Rule of thumb:What is the definition & standard of a seaworthy ship? Is is the same as for 'roadworthy cars' or higher?It was held that a ‘seaworthy’ ship contained 2 elements – (a) it is in good technical order from a mechanical engineering perspective, and (b) it has selected a passage it is capable of completing based on the information that is known about the sea. This 2 part test of ‘seaworthiness’ for ships gives it a higher standard of being deemed ready for a journey than ‘roadworthiness’ for vehicles.

Background facts:

.

Alize contracted to put their cargo on a ship, ‘the Libra’, to transport it from China to Hong Kong. However, ‘the Libra’ got caught up on high mounds of mud/shoal beneath the sea whilst on the journey and it got stuck. Around $10 million had to be paid in order to dislodge the Libra from this shoal and take measures to be able to get it into the port with the cargo. Around $13m was spent on the whole operation.

The Libra had legal insurance with Allianz, who dealt with all subsequent recovery costs and dealings. Alize were asked to pay a proportionate contribution towards the Libra’s $13 million recovery fund by Allianz. Allianz stated that the ‘high shoal’ was a natural hazard and a peril of the sea that the Libra failed to navigate, meaning that by the contract Alize were required to pay a proportionate contribution to the recovery cost of Libra. Alize denied that it was a peril of the sea that caused the Libra to get stuck. They stated that the Libra was unseaworthy before it took off, so they refused to contribute to the recovery.

This legal argument invoked the ‘seaworthiness’ principle, which across the world is enshrined in ratified treaties or statutes in countries across the world, and if not, incorporated into 99.9% of shipping contracts across the world – it fundamental to shipping law. Seaworthiness largely means that if a ship is ‘seaworthy’, and has an accident on route to its destination due to natural hazards and the ship’s inability to navigate these, all who put cargo on the ship share the risk of this happening, and all have to contribute to the recovery cost for the ship. The legal question in this matter was whether the ship was ‘seaworthy’ or not.

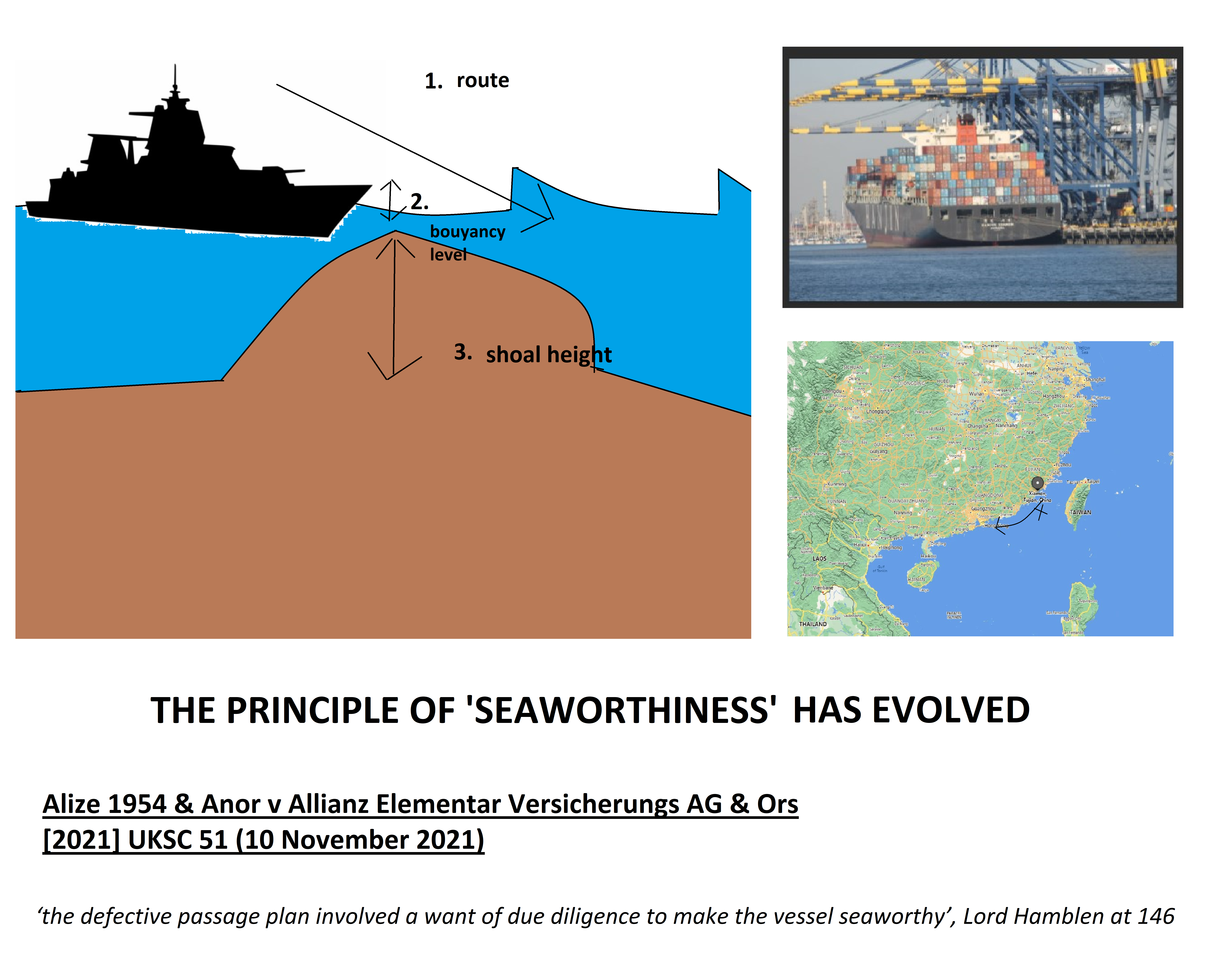

Allianz argued that the ship was ‘seaworthy’. A service was done on the ship before it left port and it was in perfect working order. Allianz argued that the mound of shoal at the bottom was a ‘natural hazard’, and one which the crew failed to navigate properly for one reason of another, which was nothing to do with the technical seaworthiness of the ship. They argued that as the ship was seaworthy and it incurred recovery costs due to accidents navigating natural hazards on route to its destination, by established shipping law, Alize had to pay a contribution to the recovery costs. Alize argued that the Libra was not ‘seaworthy’ before it set out. They stated that it was well known that a ship of the size & weight of the Libra in this case would reach a certain buoyancy level in the sea. They stated that the height of the mounds of shoal on route were known. They then argued that with the Libra’s buoyancy level known, and the height of the mounds on route also known, it was a 100% certainty that the Libra was going to crash before it set out. Alize conclude to argue that a ship setting out on a voyage that was 100% certain to crash could not be deemed to be ‘seaworthy’; a ‘seaworthy’ ship was one that set out with a reasonable prospect of completing its journey. Alize therefore argued that as the Libra was ‘unseaworthy’ with a 0% of successfully completing its journey before it set out, they had no obligation to contribute to pay Allianz a contribution for the costs of the Libra’s recovery.

Judgment:

The Court upheld the arguments of Alize and affirmed the ship was not ‘seaworthy’. The Court explained that before ships are deemed ‘seaworthy’, before every journey, (a) the ship needs to be in good running order, and (b) the ship has to be capable of actually getting through the journey they are setting out to do, and if (a) and (b) are not both satisfied then the ship is not ‘seaworthy’. The Court stated that before this ship set out, although the engine was running properly, due to the weight of it it was not physically capable of successfully completing the journey, therefore it could not be deemed to be ‘seaworthy’. In other words, there is a clear distinction between a car or lorry being ‘roadworthy’ and a ship being ‘seaworthy’. The standard for ‘seaworthiness’ is higher than ‘roadworthiness’. A lorry which would be certain to crash on a low bridge would be deemed to be ‘roadworthy’ but not ‘seaworthy’ in other words.

Ratio-decidendi:

‘The crew’s failure to navigate the ship safely is capable of constituting a lack of due diligence by the carrier. It makes no difference that the delegated task of making the vessel seaworthy involves navigation…the defective passage plan involved a want of due diligence to make the vessel seaworthy’, Lord Hamblen at 145-146

Warning: This is not professional legal advice. This is not professional legal education advice. Please obtain professional guidance before embarking on any legal course of action. This is just an interpretation of a Judgment by persons of legal insight & varying levels of legal specialism, experience & expertise. Please read the Judgment yourself and form your own interpretation of it with professional assistance.